“We just have decided that peace of mind and simplicity is better. I am able to accept that, as a result of my understanding that there are certain things I can’t do, and certain things I can do.” –Gerda Saunders

Inevitably, dementia affects a person’s identity, and it can take time to come to terms with some of the changes along the way. For Gerda Saunders, who was first diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment due to microvascular disease in 2011, some things are easier to let go of than others. Over the years, Gerda has continued to hold onto pieces of her former identity — like the relationships she has shared with her children and grandchildren, even when sustaining these bonds has become more difficult.

While participating in long conversations with her family has been increasingly challenging, Gerda cherishes simply being present for those around her. “I’d rather put up with the frustration of not being able to follow the conversation or of not understanding what the kids are talking about, rather than not be there,” she told Being Patient.

As Gerda, the retired associate director of gender studies at the University of Utah, contends with the reality of living with a terminal brain disorder, her daily experiences highlight that dementia has affected some aspects of her cognitive abilities more than others. “There are still certain things, for example — communicating with those I love — that are important enough for me to try to hang onto, but others, such as trying to entertain friends at home, are somewhat easier to give up,” she said.

With the support of her husband, Peter Saunders, she makes the best out of what she can still do, all the while, accepting what she has to let go.

Results from Gerda’s neurological tests

Marissa Saunders, Gerda and Peter’s daughter, is a data scientist. When her parents received Gerda’s neurological testing results in 2019, they asked her for help. The tests were originally summarized in a 14-page report, which the couple said was hard to make sense of. Marissa thought it might be helpful to visualize the data.

Ultimately, according to Peter, Marissa’s graphs helped the family get some clarity on Gerda’s condition, allowing them to identify aspects of her life that she needs help with, as well as areas where she can maintain her own independence.

Peter and Gerda said they’ve also been able to use these charts to help friends and other family better understand Gerda’s strengths and weaknesses.

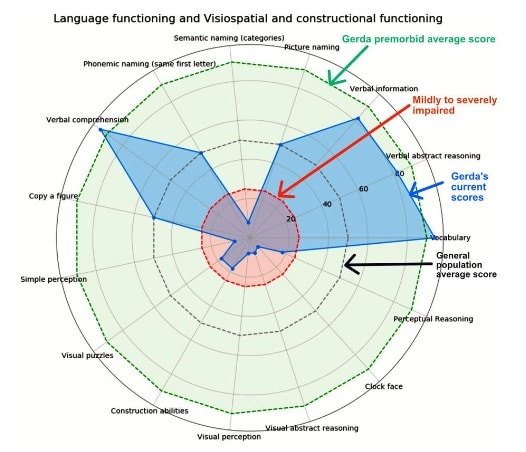

Visualizing how dementia impacts Gerda’s

language ability and her ability to navigate a space

In the above graph, “Language functioning and visuospatial and constructional functioning,” the blue shaded ‘wings’ show that Gerda’s verbal skills have remained strong, Peter noted, which explains why she can often communicate well with others. But her severely impaired perceptual and constructional abilities, as well as her impaired abstract reasoning abilities, prevent her from being able to quickly evaluate situations and make simple choices when presented with multiple options.

“People cannot imagine my level of impairment if they just hear me talk,” Gerda said. “But we’ve shown these graphs to so many people who know me well and they all just say, ‘Now I get it.’”

She continued, “They see I need help in certain things. They see me getting lost in the restaurant, trying to find the bathroom. If somebody gave me an explanation of how to get to the bathroom, I could probably recite it, but I can’t follow it in space. They always help me go to the bathroom and find my way back.” With the graph, she added, people “understood why somebody who could talk cannot find the bathroom.”

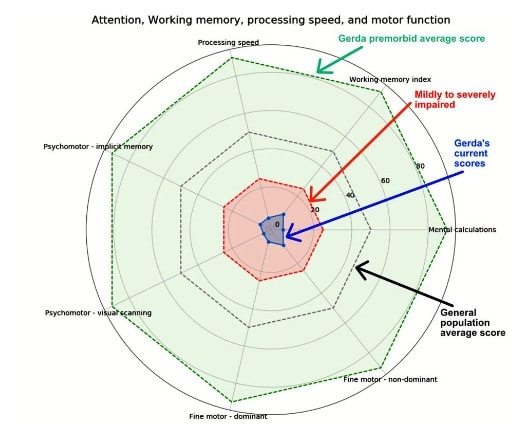

Visualizing how dementia impacts Gerda’s attention,

working memory, processing speed and motor function

The difficulties that Gerda faces in daily life are anxiety-provoking, Peter told Being Patient. But it was hard to understand just how dramatic they are until Marissa created a visualization of the way Gerda’s dementia affects cognitive factors like her attention, memory and motor functions.

In the graph, “Attention, working memory, processing speed, and motor function,” the tiny blue area in the center shows how severely impaired Gerda’s abilities are in the area of attention, working memory, processing speed and motor functions. Owing to slow processing speed, for instance, Peter said that Gerda’s ability to catch jokes, answer a question in casual conversation, or understand and deal with day-to-day logistical problems have all been eroded.

When it comes to Gerda’s fine motor skills, she often drops things, which can be a source of embarrassment, Peter said. Understanding this a little better has allowed the couple to make small modifications for comfort and convenience, as simple as, for example, switching to melamine plates rather than china plates, which are less breakable if dropped.

“We just have decided that peace of mind and simplicity is better,” Gerda said. “I am able to accept that as a result of my understanding that there are certain things I can’t do and certain things I can do.”

Some of these changes are tough to swallow for both Gerda and Peter, they told Being Patient. Fully embracing these losses, Gerda said, is a process: “You can’t rely on the previous identity. You have to accept the new identity. I accept the fact that I cannot be productive anymore in writing or a million other things that I used to do. Acceptance helps me find greater joy in the things I’m still capable of.”

All photos courtesy of Gerda and Peter Saunders.