New animal studies hint that non-hallucinogenic psychedelics could help reduce the toll of stress on the brain.

Researchers at the University of California Santa Cruz have taken the trip out of psychedelics and are delving into the question: Can these types of drugs actually help our brains?

Psychedelics are usually known for causing mystical, magical trips — temporary, altered states of consciousness, which often come with hallucinations and distortions of reality. But those trips can sometimes have terrifying side effects, and in the most severe cases, hallucinations can lead to reckless behavior and, anecdotally, even PTSD.

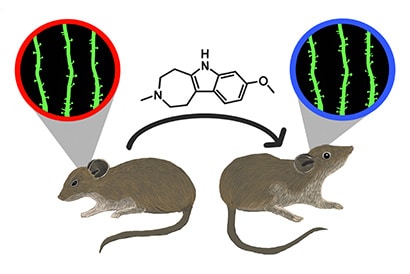

A recent animal study published in Molecular Psychiatry set out to find ways to solve two problems in one: Researchers focused on a novel compound called tabernanthalog (TBG) which appeared to negate the hallucinogenic effects of psychedelics, while rapidly reversing the damage caused by stress on the brain.

UC Santa Cruz chemical neuroscientist David E. Olson synthesized TBG and found that the compound did not induce hallucinations but still retained the antidepressant effects in mice.

“It was very surprising that a single treatment with a low dose had such dramatic effects within a day,” corresponding author Yi Zuo, professor of molecular, cell, and developmental biology at the university, said in a news release. “I had a hard time believing it even when I saw the initial data.”

A single dose of TBG corrected stress-induced behavioral deficits, including anxiety and cognitive inflexibility. Additionally, the scientists found that TBG promotes the regrowth of stress-damaged neuronal connections and restores neural circuits in the brain.

The brain contains electrically excitable cells called neurons that branch out and send signals to neighboring neurons to communicate. Prolonged stress causes neurons to atrophy, their branches to wither and shrivel up, then lose their connections with other neurons. In addition to the physical detriments, stress can also cause increased anxiety, deficits in sensory processing, and reduced flexibility in decision-making. According to the study, TBG is thought to promote the rapid formation of neuronal branches, called dendrites, and elevates their rate of survival, “leading to more newly formed [dendritic] spines being consolidated into the neuronal network.”

Want to learn more about clinical trials

for Alzheimer’s and dementia?

Check out the Lilly Trial Guide.

The synthetic compound of TBG is modelled after a naturally occurring hallucinogen extracted from the African plant iboga, called ibogaine. While this powerful drug has demonstrated anti-anxiety and anti-depression benefits, it can also cause dangerous side effects from heart arrhythmias and fatal heart attacks to neural toxicity. Olson hopes the new synthesis compound will prove to have all of ibogaine’s benefits but none of its toxicity.

TBG has a long way to go before it is determined whether the benefits found in animal studies will transfer to humans. But research is looking into whether taking specific brain-enhancing benefits could possibly possess significant advantages over classical psychedelics.