Retired neurologist Daniel Gibbs speaks about his own Alzheimer’s diagnosis, his unusual and severe case of side effects in aducanumab (Aduhelm) clinical trials, and the importance of participating in Alzheimer’s research.

UPDATE: 3 March 2024, 8:34 P.M. ET. In February 2024, Biogen took Aduhelm off the market, citing financial concerns. Although the drug did receive accelerated, conditional FDA approval for the treatment of early Alzheimer’s disease in 2021, it is no longer available to new patients. The company announced it would sunset trials in May 2024 and cease supplying the drug to current patients in November 2024.

The FDA’s accelerated approval of the Alzheimer’s drug Aduhelm (aducanumab) has spurred controversy in the Alzheimer’s community, with some experts certain that the approval was premature. Meanwhile, others believe the move will help usher in a new era of Alzheimer’s treatments, therapies that may slow the progression of the disease.

For Daniel Gibbs, a retired neurologist who was a participant in Aduhelm’s clinical trial, Aduhelm is a mixed blessing. While it is the first drug to be approved that targets Alzheimer’s pathology, Gibbs shares the unease of other experts who see the pitfalls of approving a drug despite little evidence supporting its benefits for patients.

At issue is also Aduhelm’s broad label for the Alzheimer’s population without restriction to early-stage Alzheimer’s, Gibbs said. The treatment has only been tested in patients with early symptoms of the disease, leaving its risks and benefits for patients in the later stages of Alzheimer’s unknown.

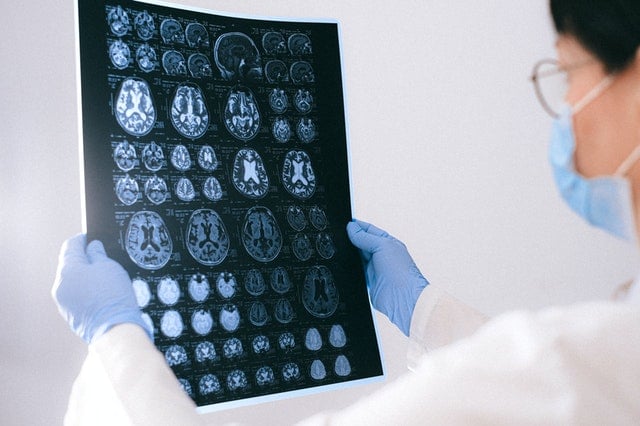

The most common side effects include amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIAs) — brain swelling or bleeding that usually do not cause symptoms. These side effects can be detected by MRI scans and often resolve over time.

Clinical trial participants who had the genetic variant ApoE4, which increases Alzheimer’s risk, appeared more likely to develop ARIAs.

Gibbs, who carries two copies of ApoE4s (roughly two to three percent of the general population has two copies of ApoE4s), experienced a unique and severe case of ARIA, an episode that gave him brief insights into the later stages of Alzheimer’s. Gibbs has since recovered, and the marks of his ARIA episode remain, inspiring the title of his book A Tattoo on My Brain.

Being Patient spoke with Gibbs about his reaction to the FDA’s decision and his participation in the clinical trial of Aduhelm.

Being Patient: What do you think about the FDA’s accelerated approval of Aduhelm?

Daniel Gibbs: I have mixed feelings about it. I really come at it wearing two different hats. As somebody living with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease and a participant in the aducanumab study, I can’t help but be pleased that the drug was approved. The drug shows the ability to remove amyloid from the brain and it’s effective at least in some people in slowing cognitive decline.

Wearing my neurologist’s hat, I am less enthusiastic, and there are several reasons for that. One is that there were two identical trials and one showed benefit and one did not. Biogen tried to do a post-hoc, or after-the-fact, examination of why that might have been the case, picked out parts of the trial that didn’t seem to show effect and tried to explain why those people should have been thrown out. But that really is not statistically appropriate to do. From a strict point of view, it probably shouldn’t have been approved without a third trial.

Having said that, if I were a neurologist practicing now, I would probably offer it to my patients with early-stage disease after fully explaining the risks and the expected benefit, or lack thereof, and letting them make the decision.

What I’m really disturbed about is the apparent blanket approval for anyone with Alzheimer’s disease. I hope that will be fixed because there have been no studies that I know of of this drug in people with even moderate Alzheimer’s disease, let alone advanced Alzheimer’s disease. And there are theoretical reasons to think, at least in my brain, that it may be more harmful in people with advanced disease because they will have a greater amount of amyloid angiopathy.

Being Patient: What’s amyloid angiopathy?

Daniel Gibbs: The amyloid that we talk about in Alzheimer’s disease is more the amyloid plaques — the sticky amyloid protein — within the substance of the brain, between nerve cells. But amyloid also is found in the walls of small blood vessels in the brain in Alzheimer’s, and sometimes people who don’t have Alzheimer’s. Almost everybody in their 80s who has Alzheimer’s will have amyloid angiopathy and it’s a major cause of big hemorrhages in the brain in the elderly.

The ARIA that we see with aducanumab and related drugs are tiny little areas of swelling and/or bleeding, but they’re not catastrophic for the most part. In fact, most people don’t even know they have them, but I worry what would happen if we gave this drug to people who have more amyloid angiopathy and who have more severe Alzheimer’s.

Being Patient: What was it like when you first saw your amyloid PET scan in 2015 as part of your involvement in a brain-imaging study?

Daniel Gibbs: That was a longitudinal study looking at amyloid PET and a then-new tau PET, which is now available commercially. I also went through two days of cognitive testing, which showed very, very mild changes, mainly in verbal memory. Everything else was fine. Seeing the amyloid was oddly reassuring because I knew specifically what we were dealing with. When you don’t know what’s going on, it’s much harder to know how to be proactive in making things better.

Being Patient: In hindsight, what were the early signs of Alzheimer’s?

Daniel Gibbs: In retrospect, my first symptoms of Alzheimer’s occurred over 15 years ago when I started to lose my sense of smell. At the time, that didn’t raise any red flags because I just thought it was natural aging. About a year later, I started to have these illusory odors that would come out of nowhere and they’re called phantosmia. Again, I thought that was interesting but I was thinking more in terms of “Well, maybe I’m going to get Parkinson’s someday because the association of olfactory disorders in Parkinson’s is much better known among neurologists.”

Alzheimer’s shows up in the brain about 20 years before cognitive impairment does. Actually, in my first PET scan, you could see amyloid in some of the olfactory parts of my brain so that was really kind of cool to see that association.

I accidentally found out I was an ApoE4 carrier. I had two copies of it, which greatly increased my chances of getting Alzheimer’s but I still didn’t have any cognitive impairment at that time [in] 2012. Then, about a year later I started to notice some things that again, weren’t particularly alarming. I had trouble remembering the names of colleagues and I could never learn the new telephone number of my new office or address. But I hardly ever used them. By that time we were using cell phones and email.

I did retire because even though I just had minimal trouble in 2013, I just didn’t want to be in the position of developing significant cognitive impairment while I was still practicing medicine because there’s just no room for that kind of possibility for error.

“Seeing the amyloid was oddly reassuring because

I knew specifically what we were dealing with.

When you don’t know what’s going on, it’s much harder to

know how to be proactive in making things better.”

Being Patient: What motivated you to join the clinical trial of Aduhelm?

Daniel Gibbs: I’ve been in four trials, and I tried out for a fifth one but was cognitively not bad enough, and so I didn’t make it into that anti-tau trial. My reason for joining trials is to try to do all I can to hurry up the process of finding something that works for Alzheimer’s.

I think everyone who has Alzheimer’s or even those who are at risk for Alzheimer’s should think about being in a trial. The reason to be in a trial primarily should be your ability to contribute to finding, if not a cure, at least drugs that help slow down Alzheimer’s, or lifestyle changes or something else. But if you go into the trial thinking that this will save me, you’re liable to be disappointed. I’d like people just to get that out of their mindset.

Being Patient: Participation is important even if people are involved in a trial that failed in the end, isn’t it?

Daniel Gibbs: All these trials are like the building blocks of a pyramid. We have a hypothesis. We test it, and then if the data supports the hypothesis, we place that block in the pyramid and the next block goes on top of it. We build on the knowledge gained before. If the hypothesis is not supported, then we revise it or we throw it out and start over. But the contribution, even to failed studies, is very, very important.

Want to learn more about clinical trials

for Alzheimer’s and dementia?

Check out the Lilly Trial Guide.

Being Patient: What was it like being a participant in Aduhelm’s clinical trial?

Daniel Gibbs: I got into a groove. There was a 6:30 [a.m.] flight out of Portland, and [I] got to San Francisco a little over an hour later. Occasionally I’d be delayed by fog because in some times of the year, San Francisco could be fogged in. If I was running late, I’d take a taxi, but otherwise I would get on the BART train and take it into San Francisco, and switch to the MUNI cable car. Then I would almost always have time to stop at my favorite coffee shop and get breakfast, and then be there in time for my infusion at 11 [a.m.] or 12 [a.m.], and then leave on a late afternoon flight to come home. It was kind of fun. I kind of enjoyed it.

Being Patient: You were randomized to receive placebo in a Phase 3 clinical trial. Then, you received Aduhelm treatment in the open-label extension of the study, where all participants received Aduhelm. Under active treatment, you experienced a severe and unusual case of ARIA. Can you share with us your ARIA episode?

Daniel Gibbs: I should say first, and this is the dogma which is largely true, that [ARIAs] are usually benign. Most people don’t know they have it. [ARIAs] are only caught on MRI scans where there’ll be little areas of swelling or little tiny areas of iron deposition from bleeding. If people have symptoms from them, they’re usually mild. Headache is the most common one, occasionally confusion.

But almost always, even with symptomatic ARIA, if you stop the drug, they’ll go away in a few months. The drug can be restarted again safely. There have been very few cases, at least that have been discussed by the maker of the drug Biogen, [of] catastrophic ARIA or serious ones, and mine was in that category.

“The little spots of hemorrhage interestingly are still there

and that gave me the title for the book. It’s the tattoo on my brain,

that little bit of iron-containing pigment.”

What they’ve discovered is that the only dose of aducanumab that seems to be effective is the highest one that was used in trial, which is 10 milligrams per kilogram. But you always ramp it up slowly to that to minimize the chance of getting these side effects.

I had received two doses of one milligram per kilogram and then two doses of three milligrams per kilogram before I started to have symptoms.

I started to have an increase in headaches. I get headaches not uncommonly so I didn’t really think anything of it, but they became a little more frequent and perhaps a little more severe but still relieved by over-the-counter [medications].

I [then] started to have just a little bit of increased cognitive trouble. What really lucked out was trouble reading, and it kind of came and went, but I’m a big reader. I read about two books a week, and I found that my reading speed really slowed down and I had to use my finger to kind of follow along with words. It got so bad that I couldn’t tell the difference between the letters ‘p,’ ‘d’ and ‘b,’ the same basic shapes with a line and a circle. But I couldn’t distinguish them. That’s called alexia, but I still had no trouble writing. I wasn’t thinking very clearly, and what I assumed was that I was just experiencing worsening of my Alzheimer’s disease. The ARIA business didn’t cross my radar at all.

Then a night or two before Christmas of 2017, I had the worst headache of my life, the kind that we as neurologists would associate with subarachnoid hemorrhage, massive bleeding into the brain. I took my blood pressure and it was sky high and remained high, so I thought I was having a stroke.

I had my wife take me to the emergency room, and by the time I got to our local hospital, I really couldn’t give a coherent history. They couldn’t get my blood pressure under control and admitted me to the intensive care unit for intravenous drugs to get my blood pressure down. I was, what we call encephalopathic, very confused. The score on my MoCA, which is the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, was 20 when I was in the ICU, so it dropped down to the clear dementia range. It’s on a scale of 30 and usually I scored about 27 or 28.

But within a few days I was doing a little bit better. My headache went away, but I still had trouble reading. Over the next month, it got a little worse. My MRI scans by that time showed this was ARIA with both the swelling and the bleeding all over my brain. Because it increased, it was felt that it should be treated. I received five doses of high dose steroids and that immediately relieved the headache and confusion. But it took about six months for the swelling in my brain to totally go away.

The little spots of hemorrhage interestingly are still there and that gave me the title for the book. It’s the tattoo on my brain, that little bit of iron-containing pigment.

Check out part II of Being Patient’s LiveTalk with Gibbs about his journey living with early-stage Alzheimer’s after more than two decades caring for patients with the disease.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Contact Nicholas Chan at nicholas@beingpatient.com

Until you’ve lived this diagnosis to death, with someone, you have no idea, what a F’ING mess this diease is…. as a Catholic, cradle to grave with this disease is punishment. Whatever it takes to find a more merciful way to live with this brain disease, please find it….. Mom, Aunt, Grandmom, and 5 great Aunts….. all died of this brain disease….