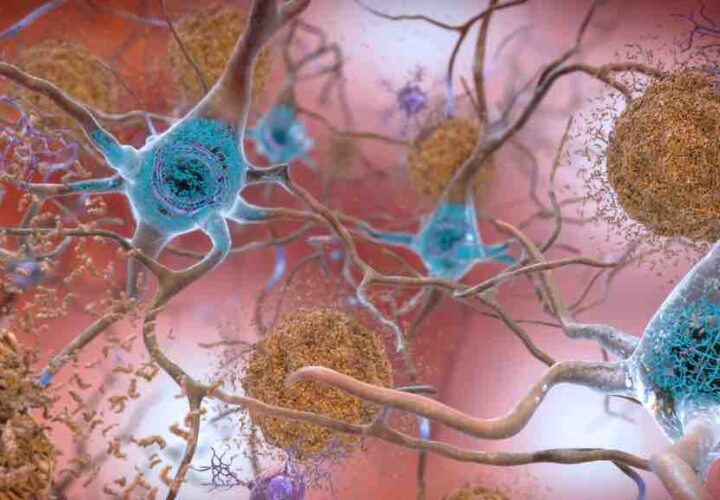

A mouse study found amyloid plaques first emerged in the deep brain structures, then spread throughout the brain in six to 12 months.

One of the most pressing mysteries of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias is how long—and where—amyloid plaques have been developing, before the disease becomes apparent through memory loss or cognitive impairment.

In a study published last week, scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) shed some light on the mystery. Using mouse models, they found that amyloid proteins—believed to be a hallmark of Alzheimer’s—begin their terrible march through the brain in as little time as a month after birth.

Amyloid plaques show up early

The research team found that amyloid plaques first emerged in the deep brain structures in the mice and then spread throughout the brain in six to 12 months (a mouse’s lifespan is approximately three years).

In a news release, lead researcher Wen-Chin “Brian” Huang said the new findings could help develop treatments that target the early development of Alzheimer’s rather than waiting until symptoms appear.

“Alzheimer’s is a neurodegenerative disease so in the end you can see a lot of neuron loss,” Huang said in the release. “At that point it would be hard to cure the symptoms.”

Huang works in the lab of study co-author Li-Huei Tsai, Picower Professor of Neuroscience and director of the Picower Institute at MIT.

“It’s really critical to understand what circuits and regions show neuronal dysfunction early in the disease,” Huang added. “This will in turn facilitate the development of effective therapeutics.”

Using the mouse model, Huang explained, allowed researchers to trace the development of the disease over time. Their findings suggest that amyloid starts deep in the brain and spreads to “increasingly complex memory and cognitive networks with age.”

The Beta-Amyloid Target

In past research, scientists examined how beta-amyloid impacts the brain over time to result in symptoms like memory loss. In one study, researchers found that beta-amyloid molecules were preventing glutamate, a chemical that plays a role in activating neurons, from working properly.

The focus on beta-amyloid as the main driver of Alzheimer’s disease—what’s known as the “beta-amyloid hypothesis”—has led to the development of several potential therapy pathways and even blood tests that can predict beta-amyloid plaques in the brain.

But failed drugs in development that target beta-amyloid, like Biogen’s cancelled trials, has led many researchers to question whether this focus is the best pathway to treatment. Now, more and more scientists are expanding their areas of research to other factors, like inflammation, that may play a role in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease.