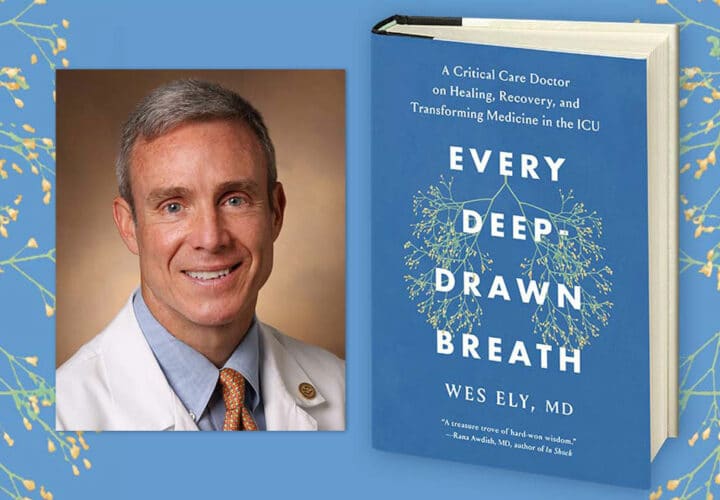

Dr. E. Wesley Ely discusses the frequency with which intensive care unit survivors go on to experience symptoms of brain dysfunction and dementia, mental health issues and other ailments. His new book Every Deep-Drawn Breath tells their stories.

More than six million people in the United States were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) annually before the pandemic hit. For ICU patients, their chances of survival have drastically improved over the last decades, but clinicians are grappling with the fact that many patients can experience cognitive, psychological and physical impairment after being sedated and immobilized for long periods of time in the ICU.

More than six million people in the United States were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) annually before the pandemic hit. For ICU patients, their chances of survival have drastically improved over the last decades, but clinicians are grappling with the fact that many patients can experience cognitive, psychological and physical impairment after being sedated and immobilized for long periods of time in the ICU.

In our LiveTalk series Being Patient spoke with Dr. E. Wesley Ely, professor of medicine and critical care at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and author of Every Deep-Drawn Breath: A Critical Care Doctor on Healing, Recovery, and Transforming Medicine in the ICU (Sept. 2021), about the personal stories of ICU survivors and their families, his own reckoning of the ways medical technologies in the ICU could end up harming people, and strategies to protect and rehabilitate ICU patients’ brains and bodies.

The following transcript has been edited for length and clarity, and the *** mark the beginnings and ends of excerpts from Ely’s book.

Being Patient: In the book, you wrote about an ICU patient of yours, Teresa Martin, when you were a resident in training. She was heavily sedated and kept on life support after an attempted suicided. She survived and went home afterwards. But life just wasn’t the same for her anymore. Tell us about your experience with Teresa.

Dr. E. Wesley Ely: The title of the book Every Deep-Drawn Breath comes from John Steinbeck’s East of Eden. It’s one of the most beautiful pieces of prose ever written, in my opinion. The title [Every Deep-Drawn Breath] really gets at the glory of the human condition, the interactions that we have with each other [in] deep, true communication. Every deep-drawn breath is sweet and the air in the room is sweet when we have real, unhindered communication with another person.

Unfortunately, many times in our lives, we don’t have such unbridled communication. In medicine, that happens a lot and I think it causes a form of injustice, which I call testimonial injustice. It’s a form of silencing of the other, which happened with Teresa, because when Teresa was my patient, she was kept deeply sedated and immobilized by me. I, at the time, thought that it was the right way to care for her. But I’m going to read to you what the interaction was like after I thought I’d done this great job, and she and her mother [came] back to the clinic.

***

Almost immediately Teresa’s mom asked, “Why can’t she bend her arms at the elbows or move her shoulders?” Her mom looked drained, more tired even than when she’d visited her daughter in the hospital. We ran through a litany of other problems that Teresa was having. She couldn’t swallow properly or sleep or go to the bathroom alone. She couldn’t shower or dress herself. She could walk only a few steps at a time, and stairs were impossible. The idea of returning to her old job as an administrative assistant was exhausting. The list of ailments was dizzying. I had no immediate solutions for any of it, and even less understanding of where the problems were coming from, so I did what I knew how to do: I ordered blood work and X-rays.

The labs didn’t show anything alarming, but the X-ray images of her arms and legs revealed large calcium deposits in her elbows, shoulders, and knees. Teresa had heterotopic ossification, a condition in which bone develops where it shouldn’t due to extreme inflammation and prolonged immobilization. It was as if she had rocks growing inside her joints. I had never seen anything like it before and didn’t know what to think.

Teresa didn’t react at all when I showed her the disturbing images, but her mother nodded in affirmation, as if she now had permission to talk about other concerns. She told me that Teresa’s brain wasn’t working properly, that she would forget things, people’s names, that she’d grown afraid. Mrs. Martin stopped and shifted in her seat. “She’s a completely different person now.” She glanced at her daughter sitting next to her in the wheelchair and sighed.

After Teresa and her mother left, I sat in the room alone, my door closed against the world. Usually when I finished with a patient, I’d ask for the next one right away. Not this time. Earlier that morning, I’d seen the name Teresa Martin on my list of scheduled patients and imagined a triumphant reunion. A cheerful “You’ve given me a whole new lease on life!” At the very least, a smile. I’d thought she would have been back at work by now, laughing with her friends, enjoying life after her close brush with death. Instead, she was a broken young woman in a wheelchair whose life now was much worse than the one she’d lived just a few months ago before coming under my care. What if she never walked again? What if her brain was permanently injured? In my gut I knew that something about the care she had received in the ICU had damaged Teresa. She had come in with failing organs, and we had fixed them, but somehow she had acquired completely different ailments. New trauma to her body and her brain. I thought I’d found my calling, pulling patients back from the maw of death, but now I wasn’t so sure. I started to wonder if saving lives was also causing harm.

***

We have to recognize in this time of the pandemic [that] this is happening to millions and millions of COVID survivors who are getting care and leaving with this form of brain and body injury. That’s even before the 100-day delay of the onset of what we all know now as long COVID. They get this first problem, which we call post-intensive care syndrome, or PICS. Then 100 days later, the immune system kicks in in a form of pathology and also creates long COVID. People are suffering from these two major problems. The least that we can do is try and organize the first part of care to create less injury and less PICS.

“Every deep-drawn breath is sweet and

the air in the room is sweet when we have real,

unhindered communication with another person.”

Being Patient: Can you tell us more about what PICS is?

Dr. E. Wesley Ely: PICS is the condition of millions of survivors of critical illness or hospitalization generally, whereby somebody leaves the hospital with these new problems: Neck up, [there’s] brain dysfunction that manifests as dementia, which looks a lot like Alzheimer’s disease. In addition, [there’s] post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and also depression. Neck down, [there’s] muscle and nerve disease that prevents them from being able to walk up a couple of stairs or do their old job, care for their house, etcetera.

So, PICS is acquired dementia, PTSD, depression and muscle and nerve disease that creates an overall body disability that stops people from going back to work and being the person that they were before.

Being Patient: How common does PICS occur in patients?

Dr. E. Wesley Ely: This occurs in probably one third to one half of people who leave intensive care. It probably occurs in about 15, 20 percent of people who just have a regular hospitalization and never even land in the ICU.

Being Patient: In the book, you wrote about the culture of “deep sedation and immobilization” in critical care. Tell us more about this culture and how it can end up harming patients?

Dr. E. Wesley Ely: In Abraham Verghese’s book Cutting For Stone, there’s a line that I use as the quote to begin one of the chapters in Every Deep-Drawn Breath, which says that the patient had scuba gear shoved down their throat, and felt like they were at the bottom of the ocean. I’ve used that analogy for years about the ICU because when we put the endotracheal tube down somebody’s throat to put them on a ventilator, and then we sedate them, it’s as if we’re submerging them in water 10, 15, 20 feet down.

But sometimes, we submerge them so deeply that they’re 100 feet down, and they’re essentially depersonalized in the ICU. Technology should be used in that way [for a] very, very, short time. I often have to do that at the very beginning of somebody’s critical illness, but I want to keep that period as short as possible.

What happened in COVID, and what happened back in the 1990s before we undid it prior to COVID, was that we kept people like that for days and weeks: Teresa Martin was kept deep down 100 feet below the water for days and weeks.

From 2002 to 2018, we studied this and proved a better way forward, which is called the safety checklist of the A2F bundle. The A2F bundle stands for the ABCDEF steps that we take in the ICU. If you or your loved one comes to the ICU, you could say to your doctors, ‘Are you using the A2F bundle? Are you complying with this because I want you to wake my loved one up every day, get them out of the bed, [and] get me as a family member next to them in the hospital.’

The F for example is family: to get [family] next to [the patient’s] bed. We abandoned [families] at the beginning of the pandemic because we were afraid of the infectivity of the virus and that did a lot of harm to people. How many people died because they lost hope or lost sight of their own selves when no one that they loved was allowed to be with them for days and weeks? I believe that people can die of a broken heart. The A2F bundle is a way to resurrect humanism in medicine and help us to do things better in a systematic fashion.

Around 2018, 2019, we were complying with the bundle in the 80 percent range all across the country and the world. Now, we’ve documented that in COVID, we’re in the 10 to 20 percent range of compliance. It’s just been completely undone and we have to find our way back.

Being Patient: What’s happening to ICU patients’ brains when they are are deeply sedated?

Dr. E. Wesley Ely: This is a conglomerate from the chapter called “Delirium Disaster.”

***

I heard one patient describe an attack by a mob of green aliens; another recounted a story about being swarmed by snakes; and yet another said he was constantly being pushed down a long, dark tunnel. I listened to story after story with a sense of growing comprehension and alarm. We had thought our ventilated patients were sleeping, protected by sedatives, paralytics, and pain medication from the intense discomfort caused by life-support machines. But clearly, they were not serenely dreaming. They were delirious, afraid and confused. When family members turned to me, looking for help in how to respond, I was unsure. Should they dismiss the stories and say that they weren’t real, or should they acknowledge them, suggest they were hallucinations and delusions? Neither response seemed especially reassuring to the patient.

***

Being Patient: Your team studied the link between delirium, cognitive impairment and dementia in the BRAIN-ICU study. Tell us more about the study’s findings.

Dr. E. Wesley Ely: In that study, we studied 800 patients and we proved for the first time that delirium is a predictor of the development of dementia. Nobody really knew that in the ICU. They thought, ‘How could you get dementia after a few weeks when dementia is something that should come on in years?’ But we felt like it was happening in extra fast time, and that is what we proved.

Want to learn more about clinical trials

for Alzheimer’s and dementia?

Check out the Lilly Trial Guide.

There’s a patient in the book named Sarah Beth Miller. There’s lots of people in the book with this problem. One day, she came in and said, ‘I’m an engineer. I’m a mathematician. I was just kicking butt life. I got sick and now I’m having to retire early. I can’t go back to work because I can’t think well. My brain doesn’t work.’ (Beth was previously admitted to the ICU after developing pneumonia, sepsis, and acute respiratory distress syndrome.)

We tested her and we told her, ‘We got your test back in, and your IQ is okay. It’s 110 to 115.’ Sarah Beth just freaked out and said, ‘My IQ is 110, 115? It’s always been 140.’ We said, ‘You’ve had IQ testing before?’ She said, ‘Yes, I’ve had IQ testing multiple times.’

We wanted to image her head, but after she got out [of the ICU], she was so depressed about her life that she got braces on her teeth. She was like, ‘I got to have something to lift me up here.’ We had to wait because you can’t put somebody in the MRI if they have metal on their teeth. When she finally gets her braces off, here’s what happened. (Miller received MRI imaging during her ICU stay.)

***

I soon had the results in hand, and what I saw was devastating. Her previous scan had not shown any signs of brain atrophy, loss of brain tissue, but this new imaging, according to the neuroradiologist, looked “like the MRI of a demented eighty-five-year-old.” Sarah Beth was fifty-two.

As anyone who observes a drawing of a brain quickly notices, the outside has a wrinkled appearance made up of bumps and grooves. These are the gyri and sulci. And on the interior, spaces called ventricles are filled with cerebrospinal fluid. This fluid courses down from the inside of the brain into the spinal canal, and it’s what doctors drain with a needle when we do a spinal tap to look for meningitis or a bleed. Since the skull encases all of this in a fixed amount of space, our heads are filled with varying amounts of brain tissue and fluid. As I stared at Sarah Beth’s latest MRI, I saw immediately that she had lost a huge amount of actual tissue. The sulci were much deeper, and the ventricles filled with fluid were larger, having grown to fill the void left by disappearing brain tissue. Millions of brain cells were missing. It was as if tons of rich soil had been removed from a garden, leaving behind puddles of muddy water and a few wilted perennials. Two areas of her brain showed especially significant degeneration, the hippocampus and the frontal lobes, regions that specialize in memory and executive function. This made sense. She had told us about her forgetfulness and her inability to organize her life. It was sickening to look at, yet I couldn’t pull my eyes away. I saw the scan of Sarah Beth’s badly damaged brain as a map of her muddled and tangled thinking. Visible confirmation of an invisible illness.

***

Being Patient: How do physicians help and treat patients like Sarah then?

Dr. E. Wesley Ely: What we’re finding is that even months or years later, we can [offer] cognitive rehabilitation. Let’s say I get bonked on the head with a car wreck. I will have a macro form of injury in my brain. In a CT scan, you’d see a big stroke or a bleed in my head. What Sarah Beth has is micro injury, meaning that all over her whole head, she’s got millions of lost neurons.

What do we do for that? We give exercises like Sudoku and scrabble, brain exercises that actually work the brain like you would work your bicep, like you would lift weights and do curls to build that bicep back. If I put your arm in a cast after it was broken, and I took the arm out of the cast 12 weeks later and your arm was all shriveled up, you’d go back to the gym and start rehabbing your arm. We need to rehab the brain the same way.

Watch the full conversation with Dr. Ely on video here.

Contact Nicholas Chan at nicholas@beingpatient.com