First it was a diabetes drug, now researchers have turned their attention to an HIV drug. Could a drug that would slow down Alzheimer’s disease already exist?

Researchers from Brown University think that could be the case. A new study has found that a drug created to treat HIV reduces inflammation—long implicated in Alzheimer’s as a potential cause of the disease—and other signs of aging associated with neurodegenerative diseases.

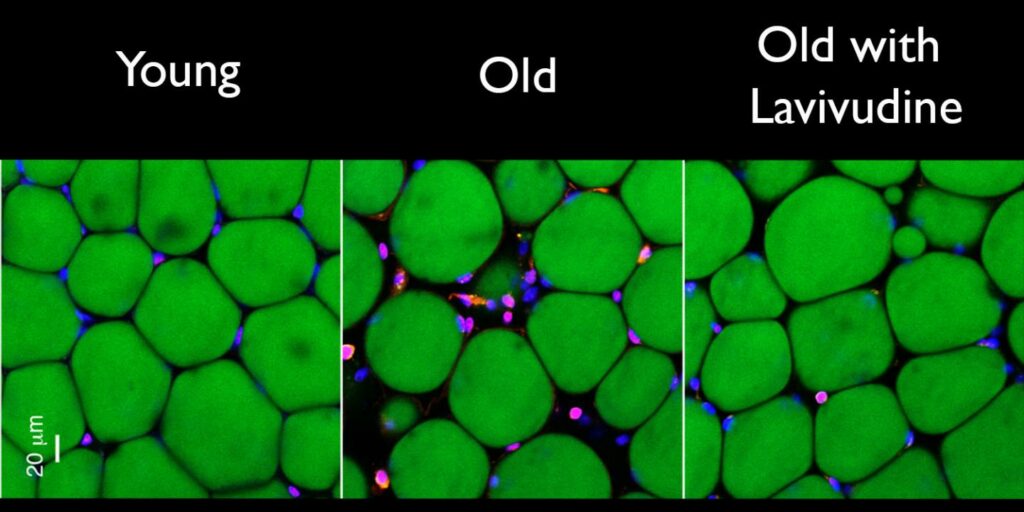

To test the drug, called lamivudine, scientists gave it to 26-month-old mice—the human equivalent of a 75-year-old. Those mice saw a significant reduction in inflammation. When they gave it to 20-month-old mice, they saw less fat, muscle loss and kidney scarring. Of the six HIV drugs they tested, mice had the best response and the least amount of side effects to lamivudine.

“This holds promise for treating age-associated disorders including Alzheimer’s,” said John Sedivy, professor of medical science and biology at Brown University. “And not just Alzheimer’s but many other diseases: Type 2 diabetes, Parkinson’s, macular degeneration, arthritis, all of these different things. That’s our goal.”

Here’s how the drug works: It stops DNA replication and movement—a process called retrotransposon—from occurring. Because this process is related to the spread of viruses, the body typically stops the genes from replicating and traveling elsewhere on its own. But older cells can fail to control the retrotransposon.

The researchers found that certain types of retrotransposons called L1 were able to escape and start to replicate in human cells and the cells of older mice. These fugitive cells trigger an immune response called interferon, which causes inflammation in the body. This inflammation, the researchers believe, can lead to all sorts of age-related conditions.

“This interferon response was a complete game changer,” Sedivy said.

Researchers realized that the L1 retrotransposons and viruses like HIV both require a specific protein to kick off the inflammation. These proteins, called reverse transcriptase, are halted by many HIV drugs, including AZT, the first drug to treat AIDS. If a drug could prevent the genes from replicating, it could also stop the inflammation response.

“When we started giving this HIV drug to mice, we noticed they had these amazing anti-inflammatory effects,” Sedivy said. “Our explanation is that although L1s are activated relatively late in senescence, the interferon response reinforces senescence-associated secretory phenotype response and is responsible for age-associated inflammation.”

Senescent cells are older or damaged cells that have stopped replicating. These zombie-like cells produce inflammation and promote conditions like arthritis and cataracts.

The researchers saw results in mice in as little as two weeks. The drug was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1995 and is considered a safe drug with minimal side effects.

“If we treat with lamivudine, we make a tangible dent in the interferon response and inflammation,” said Sedivy. “But it doesn’t quite go back down to normal. We can fix part of the problem, but we don’t actually understand the whole aging problem yet. The L1 reverse transcripts are at least an important part of this mess.”

Next, Sedivy’s team would like to test the drug in humans with frailty, Alzheimer’s disease and arthritis.