Scientists are studying brain cells called microglia to better understand the causes of Alzheimer’s — as well as new avenues for treatment.

Imagine the brain as a sprawling art exhibit: Several large marble and clay statues are visible as far as the eye can see — our neurons. The exhibit is divided into different rooms, connected to different types of statues — Renaissance, Modern, or Greek — grouping individual neurons into brain regions. Each sculpture carries a small amount of information about its artist and era, but combining the information conveyed by multiple sculptures, organized in interconnecting rooms gives a better idea.

But neither this analogy, nor the brain’s development, would be complete without discussing the sculptors that make it all possible: microglia. These small round cells help the brain refine the connections between individual neurons, sculpting out any unnecessary appendages and links. Afterward, they act as sentries that clean up damage and debris, protect against infection, and even regulate blood flow to the brain.

Microglia as the brain’s fixers and protectors

“For a long time, people assumed that the microglia played mainly a detrimental role through pro-inflammatory signaling pathways, since they are chronically activated around the amyloid plaques,” Brigham Young University professor David Hansen told Being Patient.

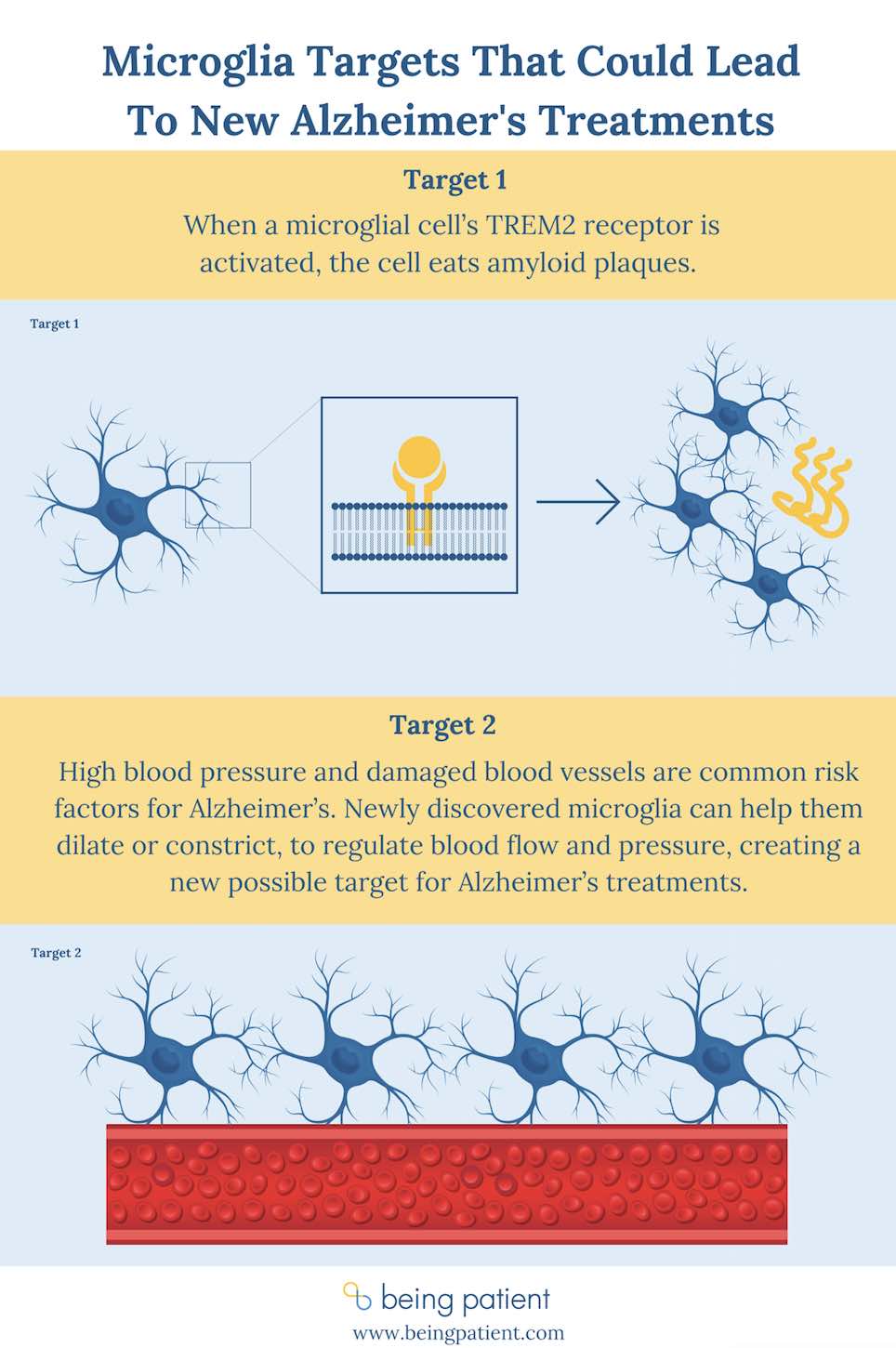

Newer studies have found that, despite this bad reputation, microglia serve important neuroprotective functions that can stave off degeneration. In fact, it appears that in Alzheimer’s, these cells’ function may be impeded, rendering them unable to repair the cellular wear and tear.

“When they’re functioning very well, microglia are able to degrade amyloid fibrils and prevent them from turning into neurotoxic plaques. And even when plaques do form, the microglia still help make the plaques less neurotoxic,” Hansen explained, adding that microglia may become compromised due to aging or specific genetic variants. From the microglial perspective, Alzheimer’s could be caused by a rapid proliferation of amyloid plaques, or if the microglia cannot clear them quickly enough.

The TREM2 receptor is a microglia protein that plays an important role in protecting the brain. This protein helps clear out or recycle debris in the brain, respond to infection and deal with other types of damage. TREM2 is occasionally shed from the cells, allowing researchers to measure its concentration in the cerebrospinal fluid. With a lot of activation of this protein, there is more turnover and more of it ending up in the cerebrospinal fluid.

“Higher soluble TREM2 levels correlate with a slower rate of disease progression,” Hansen said. “When there are more microglia, or when there’s more robust microglial response to the pathology, then that actually helps slow the rate of disease progression.”

Microglia as crowd control

To keep any art exhibit running long-term, there needs to be a steady flow of visitors. If too many people are touching and bumping into the sculptures, the wear and tear accumulate faster. Not enough, and the exhibit can’t muster the funding to stay open. The flow of visitors is analogous to blood circulation, flowing through the halls of the brain’s vasculature to deliver oxygen and nutrients.

“About a third of the microglial population is actually situated on the vasculature,” University of Virginia professor Ukpong Eyo said. “If we eliminate these microglia, we can see that the vasculature diameter actually increases.”

This situates the microglia as perfect targets for potentially preventing Alzheimer’s disease: High blood pressure is a large risk factor, while individuals taking certain drugs to lower blood pressure are at a reduced risk.

Eyo and his lab are excited to continue studying these microglia. Targeting the microglia could help reduce blood pressure and potentially reduce the risk of developing Alzheimer’s.

Where next?

A biopharmaceutical company called Alector is already in Phase 2 trials testing an antibody that activates TREM2, in the hopes that it will slow the progression of Alzheimer’s.

Meanwhile, Eyo and his team are carefully teasing apart the intricacies of microglia and their relevance to Alzheimer’s. For example, in animal models, microglia from male and female animals respond differently to damage from stroke. According to Eyo, these experiments suggest that microglia in females provide some kind of neuroprotection, though it isn’t yet clear what that means for Alzheimer’s disease, which disproportionately affects women — much less whether the same sex-based differences will hold true for humans.

While there are many mysteries left to solve, these researchers say, microglia — though often maligned and misunderstood — could one day help aging brains stave off Alzheimer’s.