As part of our LiveTalk series, Being Patient spoke with Dr. Daniel C. Potts about the legacy of his late father Lester E. Potts, Jr., who discovered his artistic talents in watercolor painting following his Alzheimer's diagnosis.

Expressive arts like music, painting, and even dance have the potential to evoke powerful emotion and long-buried memories in people living with Alzheimer’s. For Lester E. Potts, Jr., who was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s at the age of 72, watercolor painting became an avenue to express his life experiences.

Lester created more than 100 art pieces after discovering his artistic talents at Caring Days Day Care facility in Tuscaloosa, Alabama — and his artwork has lasting impacts: His journey with Alzheimer’s, and the creativity that emerged during that journey, changed the way his son Dr. Daniel C. Potts, a neurologist at the Tuscaloosa Veterans Affairs Medical Center, cares for patients in his own practice. After Lester passed away in 2007, Dr. Potts also established the nonprofit organization Cognitive Dynamics, educating students about Alzheimer’s and other dementias, and connecting them with people who have the disease.

Being Patient spoke with Dr. Potts about his late father’s artwork and how Lester’s journey with Alzheimer’s has taught him to better help his patients build on their strengths, to better support their caregivers, and to take care of himself as a physician.

Being Patient: Dr. Potts, can you tell us a little bit about Lester’s background?

Dr. Daniel Potts: Dad was a great guy. He was a Korean War veteran. He was a good, solid wood worker, farmer, saw miller, rural Alabama guy. He married an English teacher and so my mom and dad raised me in rural, small town Alabama. Dad was the best man I’ve ever known. He continues to be my idol and I looked up to him in so many ways.

Being Patient: How did Lester discover his artistic talents?

Dr. Daniel Potts: Creating art was not something that anyone would have believed my dad would have done or would have been interested in because he was a utilitarian child of the depression years.

But once my dad began to show signs of Alzheimer’s disease, which was eventually diagnosed as Alzheimer’s, he attended an adult daycare program here in our town, which is just a wonderful place. Dad went there and was validated and supported in his current situation and was given the opportunity to explore talents and gifts that he may still have even though there were some losses. One of those [talents and gifts] was the expressive arts.

There was a retired art teacher named George Parker that volunteered his time at Caring Days (the adult daycare center). He was not an art therapist, but he really knew how to facilitate this process and so Dad did it. Mother said, ‘Lester’s not going to do that. You can try it but he won’t do it.’

Lo and behold, my dad loved it. He painted over 100 watercolors — some of the most beautiful things that I’ve ever seen and I still look at these and say, ‘I can’t believe he did this.’

Being Patient: What do you think were some of the messages Lester was trying to convey?

Dr. Daniel Potts: There’s something I think in human beings that can well up and support us when we are being challenged like this. For Dad, I think it was his faith background, I think it was his strong family rootedness and love and I think it was those relationships that had buoyed him up all these years, and the sense of occupational identity that my dad had hung onto. He was a saw miller. He was a hard worker. He was dependable. He pulled from that deep well that was still inside of him, and I think he expressed that richness and put it on canvas.

He needed something to buoy him up and he reached in and found it with the help of others who cared for him and who knew how to facilitate this. And guess what? It also buoyed us up. I was sinking in a deep place and my mother too and all of us who loved Dad. We drew energy from the very one who was living with dementia and that energy continues to motivate me today actually. It’s unbelievable.

Being Patient: You published the book “The Broken Jar” featuring Lester’s artwork and your poetry. Can you share with us some of the artwork?

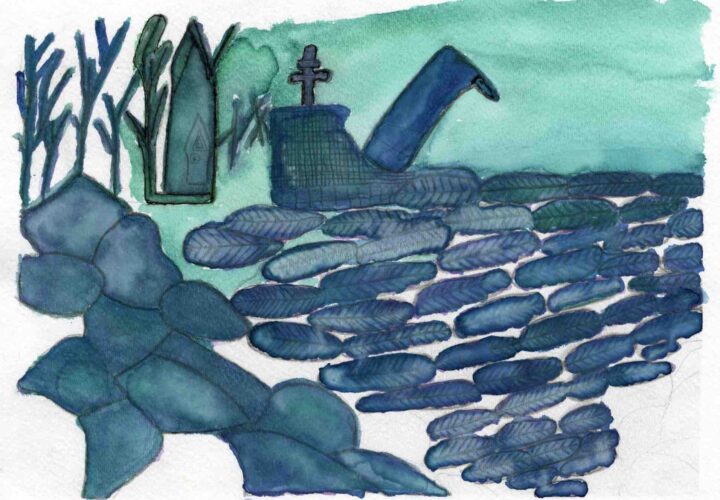

Dr. Daniel Potts: One of these paintings that’s probably Dad’s best known painting is called The Blue Collage. In this blue collage are images of his home with his father. There’s a crosscut saw. There’s a high top shoe. There’s a cross with a hat on it. That is an abstract image of Dad’s father because Big Daddy always had a hat on. He always had high top shoes and he was always pulling a crosscut saw.

At a time when Dad could not say that’s what that was, he was painting his own father. There are rocks, leaves, birdhouses which Dad used to make all the time and give people, and there are trees. This really is an abstract image of his early life.

Lester was painting his narrative in art therapy. I think one of the things that was happening was that because of the supportive care he was getting and because of the opportunity to create and be in the moment, he was able to access some of those remote memories and bring them out and support his own personhood. He was painting with his colors of yesterday on a picture of today.

When he did some of his best work, he was in the moderate stage of Alzheimer’s. He was already having terrible short-term memory loss, aphasia. He had trouble even fixing a garden gate, plugging in a lamp, dressing himself.

He even did some art in the late stages. As a matter of fact, the last image he painted in Caring Days was a saw without handles. It’s not colored. That’s different from his other art. He had so much art that was brightly colored, beautiful. He eventually came down to blues, greens and eventually no color at all. But that saw really speaks to us because that’s the tenacity, steeliness and the strength of his family right there on the canvas. He’s still there. Lester’s still there.

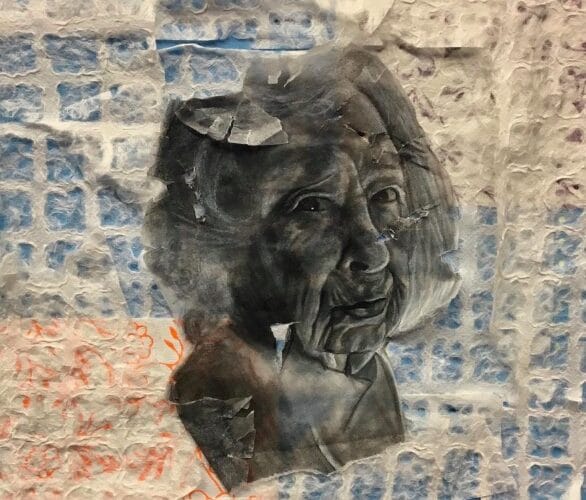

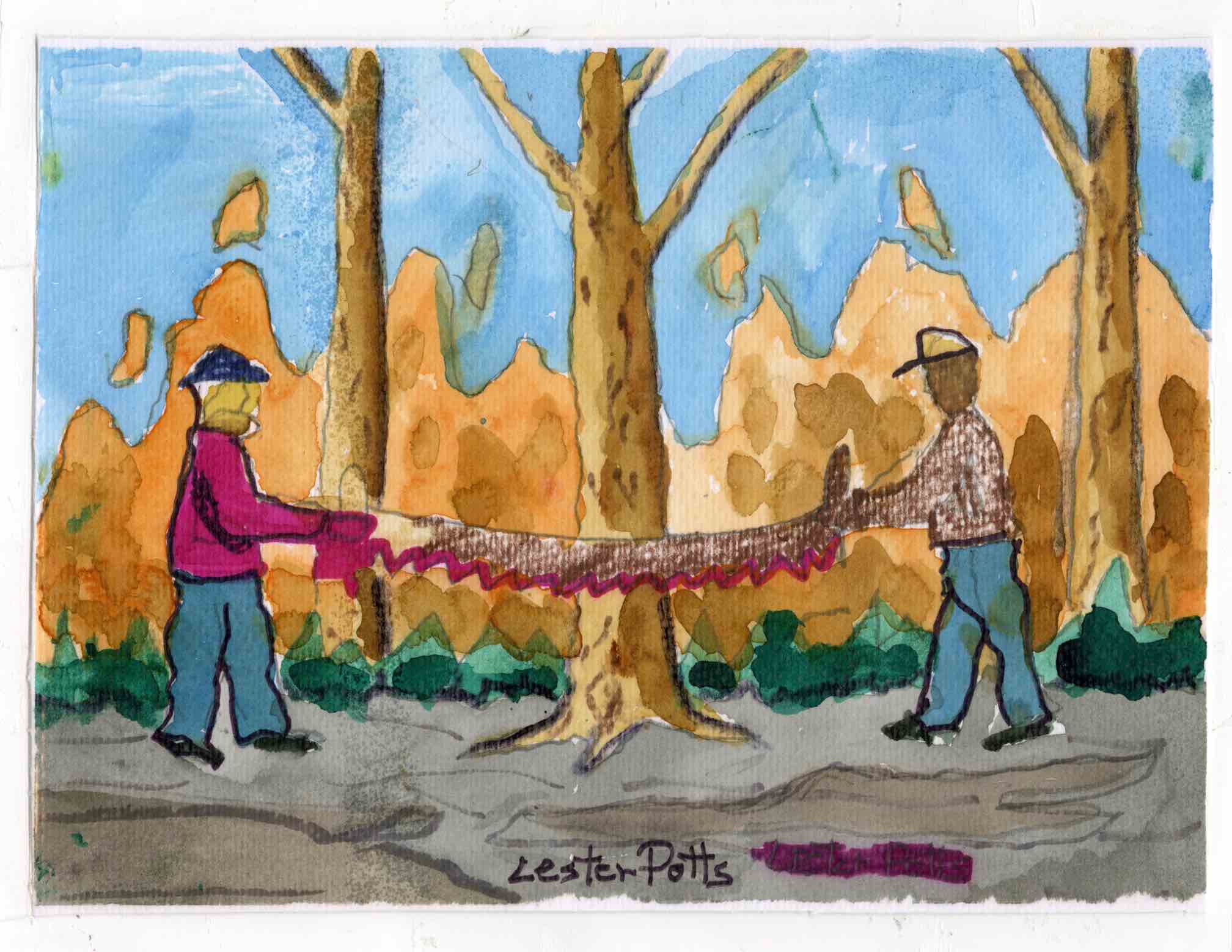

He painted a picture of him and his friend Albert Corder. When he painted that, he could not tell us who that was pulling the saw with him. There’s a white man and a Black man pulling the saw together. All their lives, they respected and loved each other. We saw that image and we said ‘Dad, is that Mr. Albert?’ All he could do was put his hand on Albert and cry.

That relationship was very important to Dad. My dad told me one time, ‘If something happens to me, call Albert.’ [The relationship] continued to be important to him even late in life when he couldn’t speak anymore. That showed me the power of relationships to buoy us through our troubles, even the trouble of Alzheimer’s.

Being Patient: The diagnosis must have been very tough for both Lester and the family.

Dr. Daniel Potts: It was a dark time. I don’t want to minimize the effects that people have to deal with with this condition. Dad was depressed about his losses. His language and memory was leaving etc., and he was not able to do the things that he needed to do to take care of himself day by day.

But after going to Caring Days and being exposed to the art, he blossomed. He was producing things. Some of the most interesting art that he produced was excellent memories that he had of childhood and relationships and places that he frequented as a young person.

I want to acknowledge my mother, who was the primary caregiver for Dad and who was there with him day in and day out, and who struggled mightily to bring him the best. My hat goes off to care partners, caregivers like my mother.

Being Patient: How has your experience changed the way you care for patients with dementia?

Dr. Daniel Potts: I went into neurology because his father — my grandfather — had a series of strokes that eventually took his life. I was a little boy. He was my best friend. I wanted to help people who had strokes so that’s why I went into this.

One of the primary things [that my father’s Alzheimer’s] has done is I’ve learned to try to look inside the person and not just see loss — deficits, disability that I’ve been trained to see as a neurologist — but to see what remains and to build on strengths that people have. I always try to support them through that.

It’s taught me to be hopeful in this and other conditions that seem on the outside to be hopeless. It’s taught me that I need to listen to caregivers, care partners and support them better. It’s taught me that I need to take care of myself as a physician because one of the things that happened to me was that I burned out. My family and I struggled through that burnout. But my own father and his carers showed me that I’ve got to be compassionate toward myself or I can’t be compassionate toward anybody else.

I always listen to the person with dementia first. When a care partner and a person with dementia come to my office, I always make a point to listen to that person first because that’s the patient, even though they may be confused about some of the details. We can fill those in a minute, but I’ll always focus on that human being. I believe that I can help people live well now because I’ve seen people help my dad live well. I know I can’t cure things at this point, but I do the best I can to give people the resources they need and the support and tools they need to live well with this condition.

All photos courtesy of Dr. Daniel Potts via LestersLegacy.com. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.