The blood-brain barrier is a wall of defense between toxins and pathogens in the bloodstream, and the brain. Blood-brain barrier damage has been linked to — among other brain health issues — neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s. For scientists seeking to understand how to prevent or treat neurodegeneration, a better understanding of why this wall of defense may break down, and of the cells that help to maintain it, is crucial.

Recently, some scientists have called into question a long-standing hypothesis that certain star-shaped brain cells known as astrocytes support the integrity of the blood-brain barrier. But in a new study, researchers have found that astrocytes are indeed essential to blood-brain barrier health — a discovery that study senior author Dr. Stefanie Robel said can help us better understand what goes wrong in traumatic brain injury, in Alzheimer’s disease, and in other health problems associated with blood-brain barrier damage.

“Blood-brain barrier leakage is a problem in the aging brain as well as many different neurological diseases,” Robel, an assistant professor at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at Virginia Tech, said in a news release. “Without astrocytes, the blood-brain barrier becomes leaky and ineffective, leaving brain tissue vulnerable to a variety of medical conditions.”

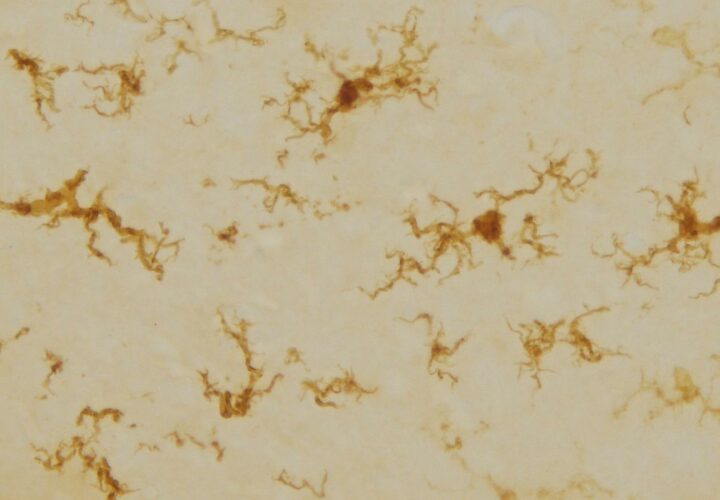

Astrocytes are a type of glial cells in the central nervous system that help maintain a stable environment in the brain through a broad range of functions including regulating communication between neurons and the immune response of the brain. The networks of human astrocytes are extensive: not only do they interact with networks of glial cells, but they also signal to the junctions known as synapses where neurons release chemical messengers. And scientists hypothesize that astrocytes play a key role in consciousness and the formation of memory.

In a study published in the journal GLIA, Robel and colleagues disrupted the genes of adult mice’s astrocytes, mimicking the effects of removing their cells to determine whether the astrocytes are necessary for the health of the blood-brain barrier.

By using molecular tracers of various sizes to examine how permeable the mice’s brains became, the scientists found that all the markers passed through certain areas of the barrier. In other regions of the blood-brain barrier, only small tracers seeped through. These are indications that there were leakages in the barrier of various sizes. And neighboring astrocytes did not rescue the damaged blood-brain barrier.

According to Benjamin Heithoff, an author of the study and a graduate student who conducts research at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute, this can tell us that there may be long-term dysfunction in the barrier.

“When people sustain a concussion, we used to consider this a ‘minor injury,’ but our follow-up study shows that the blood-brain barrier leakage persists in areas where astrocytes are not functioning correctly, which suggests there is a long-term, lasting dysfunction in the barrier,” Heithoff said.

“Understanding how that problem occurs and how it can be remedied are important public health questions,” he continued. “We have to know what makes this barrier functional in order to develop effective treatments when it becomes dysfunctional.”

Contact Nicholas Chan at nicholas@beingpatient.com