Scientists have discovered that the cells linked to Alzheimer’s disease are far more diverse than previously thought. In a new study, researchers examined what’s known as glial cells — cells in the central nervous system that help maintain and protect the brain’s neurons. The study provides a basis for researchers to understand how glial cells function in neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s.

Researchers once assumed that glial cells were passive cells that filled the space around the brain’s neurons. Over the last 20 to 30 years, however, they have found that glial cells possess functions every bit as vital as those of neurons. Glial cells supply nutrients and oxygen to neurons, clean up brain debris and help hold neurons in place.

It’s well-established that neurons are organized into different layers in the cerebral cortex of the brain, each layer consisting of different types of neurons with unique functions. Until now, researchers didn’t know whether glial cells had complex layers like neurons.

“We asked the question [of] whether glial cells show a similar amount of diversity and heterogeneity,” Dr. Omer Bayraktar, group leader at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, said in an interview with Being Patient.

The researchers examined a type of glial cell called astrocytes in mice and human brains. Astrocytes maintain the balance of ions around neurons, synchronize blood flow to the brain and manage the activities of axons—nerve fibers that transmit information to different neurons.

The scientists developed a novel method called large-area spatial transcriptomic (LaST) to map the gene expressions of astrocytes within the cerebral cortex, a region of the brain that regulates speech, thinking and memory. They combined the maps with single cell genomic data, creating a three-dimensional, high-resolution picture of astrocytes within the brain.

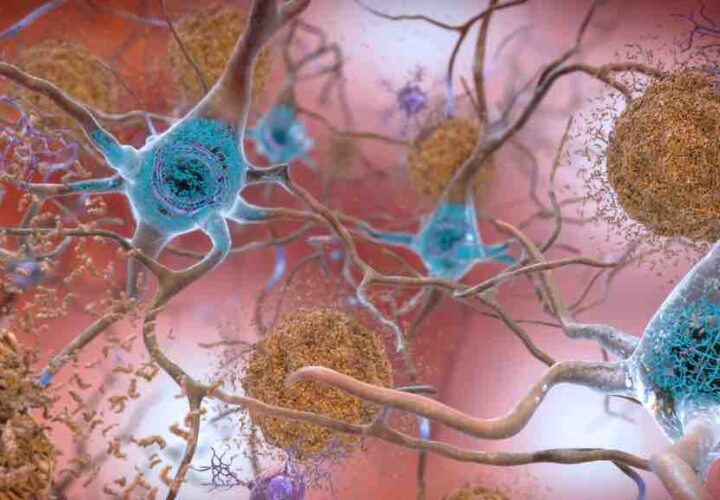

The team’s findings show that the structure of the cerebral cortex can no longer be seen simply as the structure of neurons, the researchers said. They found that astrocytes have distinct molecular forms in different regions of the cerebral cortex. Astrocytes are also organized into multiple layers that overlap neuronal layers in the cerebral cortex. While the structures of neuron and astrocyte layers are similar, the layers of astrocytes appear to have less sharply-defined edges.

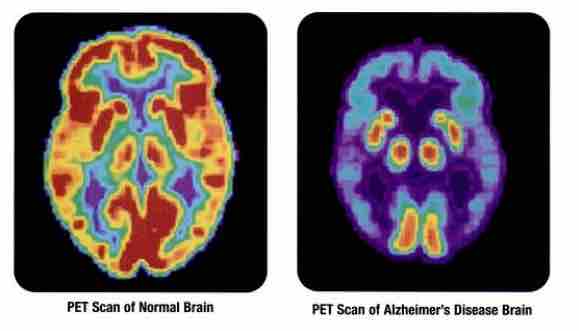

“The different roles that different brain cells play … are very, very intimately linked to how they function or dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases,” Bayraktar said. “To be able to understand what happens at the cellular or molecular level in neurodegenerative diseases, you need to understand what different cell types are doing in the healthy brain and then observe how those functions are altered in the disease.”

Previous research has shown that astrocytes are linked to brain health and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. In one recent study, researchers developed a drug that blocks a receptor of astrocytes in mice, improving their brain function and ability to learn new tasks. Scientists have also found that astrocytes in patients with Alzheimer’s produce more beta-amyloid—an abnormal protein that is a biomarker of Alzheimer’s—than in people without the disease.

Not only will the latest study expand researchers’ knowledge about astrocytes, but its new methodology will also enable scientists to compare how molecular properties of glial cells in brains with Alzheimer’s differ from brains without the disease, Bayraktar said.