Blood tests intended to detect signs of Alzheimer's in a non-invasive and affordable way are under rapid development. In one recent study, scientists have designed a blood test that detects 19 different blood proteins associated with Alzheimer's.

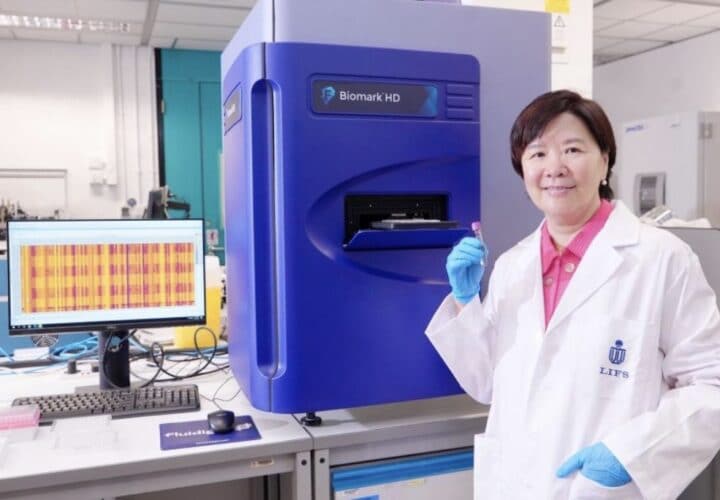

Using the blue device (pictured) that performs the ultrasensitive proximity extension assay technology, Professor Nancy Ip Yuk-Yu and her team have developed a blood test for early detection and screening of Alzheimer’s from Chinese patient data, with an accuracy level of over 96 percent. Image courtesy of the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

An hour answering cognitive health questions, drawing blood, testing urine, 90 minutes in a magnetic resonance imaging scan, and sometimes, a lumbar puncture, drawing fluid from the spine: This is the process that a person must through to properly diagnose Alzheimer’s disease. The long drawn out process is exhausting and, for many, unaffordable — two of many reasons why researchers are scrambling to find a more efficient alternative.

The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology is one of the latest research institutions developing a single blood test that allows early detection and screening of dementia, according to the lead scientist Professor Nancy Ip Yuk-Yu, neuroscientist and vice-president for research and development at the university.

“With the advancement of ultrasensitive blood-based protein detection technology, we have developed a simple, non-invasive and accurate diagnostic solution for AD,” Ip told Being Patient. The blood test is designed to capture changes in novel protein biomarkers linked to Alzheimer’s, and even help differentiate various stages of the disease.

With an estimated price tag of around $100 USD, the new blood test is relatively inexpensive and affordable compared to current diagnostic methods, which can cost as much as $10,000. It is also less invasive and can be made available in more countries.

In recent years, alteration of the Alzheimer’s blood profile has been increasingly recognized as a potential diagnostic tool. The most recent ones include the C2N test and P-tau blood tests, which examine the presence of beta-amyloid proteins in the blood as an indicator of beta-amyloid plaques—a hallmark of Alzheimer’s—in the brain, and certain forms of tau protein in the blood to detect both tau and amyloid pathologies in the brain, respectively.

While these tests each only use a single biomarker to detect Alzheimer’s, the new blood panel from Hong Kong looks at 19 different plasma proteins. Ip said this will help researchers to “achieve a highly accurate classification and staging of the disease.” In fact, studies so far show 96 percent diagnostic accuracy — higher than the existing, more invasive approaches for diagnosis.

Ip also noted that the blood panel can be used to monitor the progression of Alzheimer’s over time, which would “greatly facilitate population-scale screening and staging of the disease.”

“While the test was not a cure for the disease, early detection would allow early management and closer monitoring to slow the rate of deterioration,” Ip said, adding that she hoped that this may also pave the way for “novel and effective AD therapeutic treatments.”

As the most comprehensive study of blood proteins in Alzheimer’s patients to date, the work has recently been published in Alzheimer’s & Dementia.

Why is early diagnosis important?

For people with Alzheimer’s, neuropathological changes start to accumulate in the brain 10 to 20 years before the first clinical sign of dementia. Although early intervention in the disease would greatly improve disease prognosis, the current tribulations involved in accurate early diagnoses means that many patients miss the “golden period” for therapeutic intervention or disease management, resulting in poor outcomes.

An early diagnosis also increases one’s eligibility for a wider variety of clinical trials, which contribute to research and involve regular monitoring from doctors.

Last, early diagnosis gives people living with Alzheimer’s and their families the opportunity to play a more active role in their own healthcare, making lifestyle changes to prioritize health include exercising, quitting smoking, and staying socially active. These are just a few of the lifestyle changes that have been shown to help delay dementia symptoms.

What’s next for Alzheimer’s blood tests?

Don’t get too excited yet: Clinical studies of the 19 plasma protein test will have to be replicated to validate its performance and clinical value in other populations.

Still, Ip and her colleagues hope that this blood test “becomes a routine clinical test for aged individuals to achieve early screening and diagnosis of AD.”

Since the test only requires a small volume of blood (just a little more than a tablespoon), the researchers are considering the possibility of self-testing: obtaining a blood sample from pricking your fingertip and sending it off to the lab. Optimizing the process of sample collection may eventually enable self-testing.

However, Ip suggests that self-testing may be some way off, due to concerns about obtaining a sterile blood sample.

Ip said the findings go beyond just the development of a high-performance, blood-based clinical Alzheimer’s test: This research also identifies new protein targets for Alzheimer’s, setting the stage for the development of new therapeutics in the future.

The new blood plasma test is only one of many that will debut in the coming few years. So far, the only commercially available test is C2N Diagnostics’ PrecivityAD, available in every U.S. state except New York, as well as Puerto Rico.