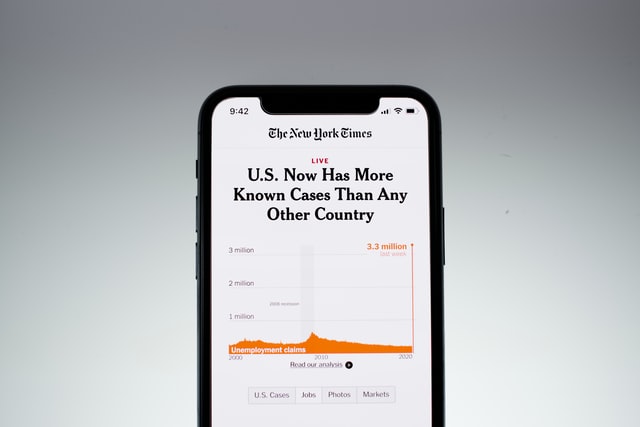

At AAIC, scientists from around the world shared new findings on COVID-19 risk factors for cognitive impairment, as well as factors could help protect the brain.

A large percentage of people who develop COVID-19 go on to experience cognitive problems. The virus’s detrimental effects on memory, clarity of thinking, ability to focus, and more may persist for months after the initial infection. Experts around the globe are already investigating the relationship between this post-COVID cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. On July 31st, several research groups reported their findings at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

A research team in Argentina discovered that after older adults became infected with COVID-19, the loss of smell was a stronger predictor of cognitive impairment than the severity of the disease. Another group discovered that older individuals hospitalized in the intensive care unit had double the risk of developing dementia, though it isn’t clear if this increased during the pandemic. Meanwhile a study conducted in Latin American countries identified protective changes during the COVID-19 pandemic that were linked to a reduction in cognitive symptoms.

“COVID-19 has sickened and killed millions of people around the world, and for some, the emerging research suggests there are long-term impacts on memory and thinking as well,” Heather M. Snyder, Ph.D., vice president of medical and scientific relations at the Alzheimer’s Association, said in a news release. “As this virus will likely be with us for a long time, identifying the risk and protective factors for cognitive symptoms can assist with the treatment and prevention of ‘long COVID’ moving forward.”

Loss of smell as a predictor of cognitive impairment

Argentinian scientists followed more than 750 older adults who were exposed to COVID-19 for a year, assessing their physical and cognitive health. More than seven in eight individuals developed an infection after exposure. Two-thirds of the adults who caught COVID-19 showed memory impairments more than a year after their infection.

To the researchers’ surprise, the degree of cognitive impairment was best predicted by the persistent loss of smell — but not the severity of the infection. The loss of smell occurs when cells in the olfactory cortex that are responsible for processing this sense die off.

“The more insight we have into what causes or at least predicts who will experience the significant long-term cognitive impact of COVID-19 infection, the better we can track it and begin to develop methods to prevent it,” said Gabriela Gonzalez-Aleman, LCP, Ph.D., professor at Pontificia Universidad Catolica Argentina, Buenos Aires who presented the study.

Interestingly, the loss of smell could be a predictor of Alzheimer’s disease that presents years before other cognitive symptoms appear.

Stay in intensive care may increase dementia risk

Scientists from the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center leveraged the Medicare claims records of more than 3,800 older adults from 1991 until 2018 to understand the link between hospitalization and dementia risk. After controlling for age, sex, education and race, they found that a stay in intensive care doubled the risk of Alzheimer’s and other types of dementia.

“More research is necessary to replicate these findings and elucidate the factors that may increase dementia risk,” said Bryan D. James, PhD, and author on the study. “For example, is it the critical illness that sends someone to the hospital or potentially modifiable procedures during the hospitalization that drives dementia risk?”

Referencing the increase in hospitalizations due to the COVID-19 pandemic, James said: “Understanding the link between ICU hospitalization and the development of dementia is of utmost importance now more than ever.”

A buffer against cognitive impairment

Researchers across Latin America and the United States looked at the impact of different life changes and demographic factors on cognitive symptoms in older individuals. They used a phone or internet survey to assess the positive and negative effects of the pandemic of more than 2,000 Spanish-speakers across Uruguay, Mexico, Peru, Chile, Dominican Republic, Argentina, Colombia, Ecuador, and Puerto Rico. Approximately 6 percent of the individuals who participated experienced COVID-19 symptoms.

Cognitive symptoms during the start of the pandemic between May and December 2020 were more pronounced among women, people with lower socioeconomic status, and people who were unemployed. Negative life changes during the pandemic which included financial challenges were associated with more cognitive symptoms. But participants who reported positive life changes such as spending more time with family and friends were able to buffer against this effect.

“Identifying risk and protective factors for cognitive symptoms during the pandemic is an important step towards the development of prevention efforts,” said María Marquine, an associate professor at the University of California, San Diego who presented the study.

Future research and partnerships will help improve our understanding of the risks and protective factors related to cognitive impairments, as well as how they link COVID-19 and Alzheimer’s.