We’ve all seen the movie: tons of hand-to-hand combat, enemy soldiers lurking behind every wall. Now place that movie in your bloodstream and imagine that the bad guys are a variety of bacteria, viruses and plaques. The heroes that save the day are the cells that comprise our immune system.

But what if, during the endless grinding wars, our hero cells go rogue?

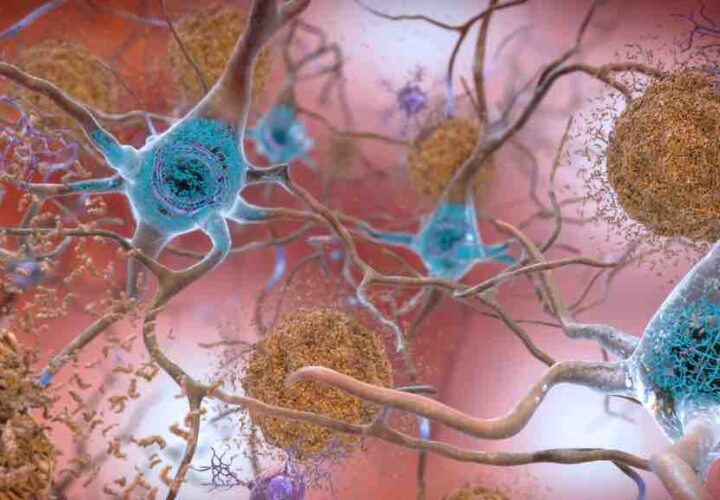

Scientists increasingly believe that inflammation—our hero cells going rogue—is one of the causes of Alzheimer’s and other dementias. One expert colorfully described the process of immune cells fighting against toxic plaques in the brain as a “smoldering battle” in which healthy brain cells “can be caught in the friendly fire.”

In a new paper, however, scientists from Australia’s RMIT University said they were successful in temporarily restoring hero status to our rogue immune cells, and using them to power memory and learning. In rat studies, they were able to alter the cells in the brain’s immune system—known as microglia—to improve performance in simple memory tests by up to 50 percent.

The researchers said their discovery suggests these cells could be targeted in the development of new therapies designed to enhance memory formation with the hope of preventing cognitive decline as people grow older.

Regenerating Microglia in the Immune System

Lead investigator Sarah Spencer said the unexpected results of the study expands our understanding of memory formation and the role of neuroinflammation in memory loss.

“Our study has for the first time shown a link between changes in the immune cells of healthy brains and improved cognitive function,” Spencer said in a news release.

“While it’s early days and a lot more research is needed,” she added, “we hope our findings may lead to new therapies that can stimulate these immune cells to boost memory and keep our brains powering as we age.”

In the study, published in the Journal of Neuroinflammation, the researchers worked with a unique type of rat to test the effect of microglia on cognitive function. The study looked at how the rats performed memory tasks when the immune system cells were present and compared this with their performance when almost all the microglia were knocked out.

They found that removing almost all the microglia made no difference in memory tasks. But when the microglia regenerated, the researchers called the results “astounding.” There was 25 percent to 50 percent improvement compared to “normal” rats.

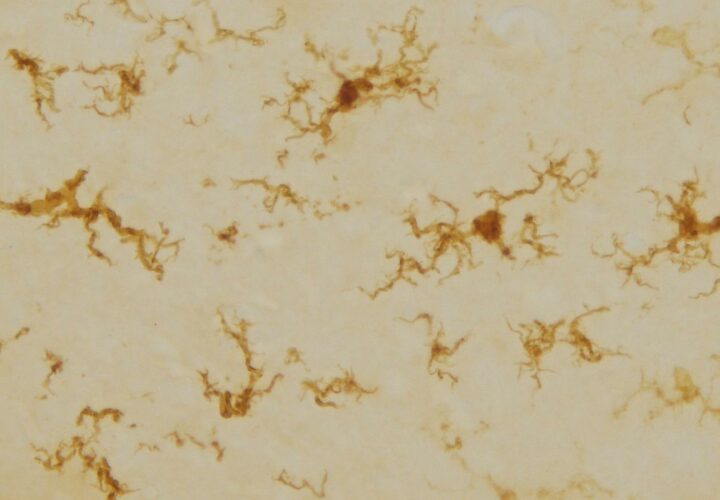

“We are still exploring what makes these cells different when they repopulate the brain, but their shape tells us they may be more active than usual, potentially making the neurons more effective to encourage better memory,” Spencer added.

“The next stage in the research,” she said, “is closely investigating these regenerated microglia to better understand the mechanisms at work, with the aim of finding ways to turn the temporary memory boost into a long-lasting effect.”

While most Alzheimer’s drugs in development have focused on reducing beta-amyloid, more researchers are beginning to design therapeutic interventions that can fight inflammation.

The Alzheimer’s Association, for example, has launched a new initiative to speed up the pace of research and is looking at neuroinflammation as a key-but-complicated mystery. “Too little inflammation,” the Association writes, “may allow amyloid plaques to form unchecked, while too much may kill vital neurons.”