As part of our BrainTalk series, newscaster Genevieve Glass speaks with Dr. Michael Geschwind about the causes of rapidly progressive dementias — relatively uncommon dementias that can potentially be treated, reversed and cured.

Unlike the slow-paced cognitive decline typical of Alzheimer’s, rapidly progressive dementias can take hold in months or even weeks in people of any age. In some cases, rapidly progressive dementia may be reversible or curable, depending on its cause.

Being Patient spoke with Dr. Michael Geschwind, professor of neurology at the UCSF Memory and Aging Center, about why rapidly progressive dementias occur and how they differ from typical Alzheimer’s and other more common forms of dementia.

- Often, rapidly progressive dementias (RPDs) are caused by prion diseases such as Jakob-Creutzfeldt disease.

- While RPDs can be caused by prion diseases, there are other causes of RPDs — such as blood clots and autoimmune conditions — that are potentially curable.

- The survival of patients with RPD vary depending on the condition’s root cause. For patients with Jakob-Creutzfeldt disease, the median survival rate is about four to seven months.

- While it is rare, Alzheimer’s can be a cause of RPD.

Being Patient: What are rapidly progressive dementias?

Dr. Michael Geschwind: There is no set definition for a rapidly progressive dementia or RPD. I usually use the definition of a person going from normal cognition to dementia in less than two years. Usually, it’s a matter of weeks to months from normal cognitive function to dementia.

I define dementia as somebody who is impaired in one or more cognitive domains — memory, language, visual-spatial function, executive function, organizing, planning, multitasking — that they can no longer function the way they could prior to the onset of the condition. There has to be functional impairment due to cognitive dysfunction and usually it occurs over weeks to months. But I extend it up to two years.

Although the survival of most of the patients with prion disease is less than a year from onset, let alone onset to dementia which is much shorter — we do have patients who sometimes have a slower course of prion disease and they may not develop full dementia until up to two years or sometimes even longer. But the vast majority of RPDs, we’re usually talking about somebody who has less than a year from onset of symptoms to development of functional impairment due to cognitive dysfunction.

Being Patient: What are the causes of RPD?

Dr. Michael Geschwind: I tend to categorize rapidly progressive dementias into different etiologies, different causes. I use a mnemonic to help me think through all the different possible causes. The mnemonic that I like is called VITAMINS, where each letter of the word refers to a different etiologic cause.

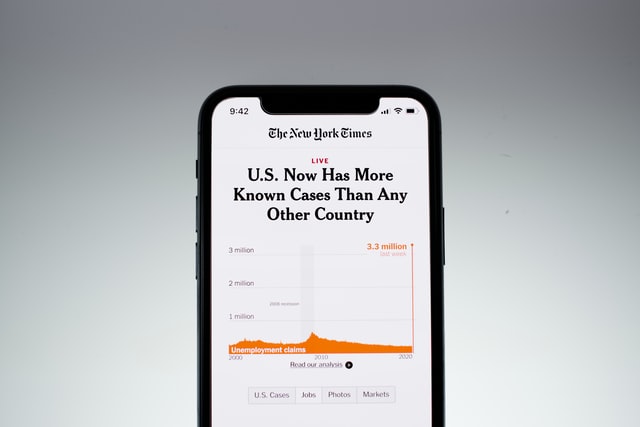

‘V’ is for vascular. Vascular could be strokes, vasculitis where you have inflammation of the blood vessels, blood clots. We’re in COVID now and there are patients who are developing blood clots in the brain and that would be a cause. Medication can sometimes cause it. Certain bodily states like pregnancy can lead to a hypercoagulation. Cancer can lead to increased clotting.

‘I’ is for infectious. COVID-19 would be one possible example. Usually, COVID-19 doesn’t directly affect the brain. It’s very rare to find the virus in the brain. It’s usually through secondary effects that you get neurologic involvement. [Other examples include] herpes encephalitis, Lyme disease, HIV — all of those can affect the brain.

‘T’ would be toxic metabolic: vitamin excesses, vitamin deficiencies, disorders of nutrition, different drugs of abuse, different drugs that you’re given to treat something sometimes have side effects.

The ‘A’ is for autoimmune – usually antibody-mediated etiologies. Sometimes these antibodies occur spontaneously, sometimes they’re the body’s reaction to fighting off a cancer and those antibodies accidentally cross-react not only attacking the cancer but also attacking the brain or the nervous system.

The next would be ‘M.’ I use M for a couple of things. Mitochondrial disease [is one]. The mitochondria are the energy or the building blocks of the cell. Disorders of mitochondria [occur] often through genetic mutations in one’s mitochondrial DNA or one’s regular nuclear DNA … Then, metastases if somebody has cancer and it spreads sometimes to the brain – that’ll be another ‘M’ in the VITAMINS mnemonic.

Then another “I” of VITAMINS is iatrogenic, usually caused by medical intervention. Usually, it’s medications that cause it. Chemotherapy for example can sometimes have side effects that can lead to rapidly progressive dementia – radiation therapy as well.

The next is “N” for neurodegenerative, and for neoplasm being a cancer either directly invading the brain or affecting the brain or through antibody-mediated process.

The last letter ‘S’ I use for a couple of things. Seizures [is one]. Sometimes patients can have seizures and they’re non-motor seizures so they’re not obvious. ‘S’ can be systemic disease, sometimes autoimmune, rheumatologic, cardiac diseases, diseases of the liver. The other things I use for ‘S’ are structural. Sometimes there can be structural changes in the brain, such as maybe a mass, maybe a tumor, maybe not a tumor such as a cyst, that actually are interfering with the flow of spinal fluid or are growing large and impinging on part of the brain. Sometimes, one can have a leak of the spinal fluid. That can often happen to someone who overexerts themselves or has trauma … If that spinal fluid leaks, the brain can sag and it pulls down on the veins and the nerves that are connected to the brain, and it can compress the top of the spinal cord and the brainstem.

Being Patient: How are typical cases of Alzheimer’s and other dementias similar and different from RPD?

Dr. Michael Geschwind: I would think of it as a Venn diagram, where you have two circles overlapping and the overlap would be extraordinary. The symptoms alone don’t usually differentiate rapidly progressive dementia from other dementias. It’s the time course of the presentation of those symptoms.

All the symptoms you see in a slower dementias — Alzheimer’s disease where you have episodic memory loss and later on in the disease you have long-term memory loss, Parkinson’s disease where you have motor dysfunction, frontotemporal dementia where you have a lot of behavior and personality changes, Huntington’s disease where you have abnormal increased movements — all of these things can occur in rapidly progressive dementia, but the time course, the evolution of the onset of these symptoms is faster. That’s usually what would tell somebody, ‘This isn’t a normal dementia. This is rapidly progressive.’

It’s important to know that because like that Venn diagram, there is a similar workup or differential, but there are things that normally you wouldn’t think of for a slow dementia.

Being Patient: Is there a way that you can rapidly reverse symptoms?

Dr. Michael Geschwind: That’s what sometimes differentiates RPD from regular dementia – many RPDs, not all of them, are completely reversible or at least treatable. Some are curable and some you can at least stop it from progressing. It really depends on the category. If they were strokes, you can intervene to stop the strokes. Some of the damage might be done and it might be hard to recover from. If it’s a clot in the brain that you catch early enough, those are usually 100 percent curable and reversible. Inflammation of the vessels in the brain – often very reversible. Autoimmune causes, depending on the type of antibody and whether there’s a cancer associated with it or not, can be highly treatable, very curable and even if it’s not curable, somebody can have a long life if you treat it effectively.

One of the most common causes of rapidly progressive dementia are atypical presentations of other neurodegenerative diseases. That’s one of the terms you can use for the ‘N’ in VITAMINS. Alzheimer’s disease rarely presents as rapidly progressive dementia, but Alzheimer’s is really common. If you look at the numbers of patients who have an atypically fast presentation of Alzheimer’s, that would be a large portion of RPD. So, atypical presentation of a typically slower dementia would be a pretty common cause … Prion disease — CJD (Jakob-Creutzfeldt disease) — that’s also neurodegenerative disease … Those neurodegenerative diseases, we don’t have any cures for them right now.

But it still would help us to know that this patient has a neurodegenerative disease such as Alzheimer’s or CJD or Parkinson’s, because then we can at least put them into the right treatment trial, and we can help prognosticate what their expected time course might be, what medications might help, what to expect over time and how to relieve the symptoms that arise.

Being Patient: What are the symptoms of CJD?

Dr. Michael Geschwind: I call prion disease the great mimicker because CJD, which is the predominant form of human prion disease, can look like anything. Many different parts of the brain can be involved. A patient may present depending upon where the disease starts. If the disease starts in the visual processes of the brain, the patient might have visual symptoms. If it starts in the hippocampus, they might have short-term memory problems. If it starts in the parietal lobe, particularly the right parietal, they might have visual-spatial processing problems. If it starts in the frontal lobes, they might have behavioral, personality, executive function changes. If it starts in the cerebellum, or areas of the brain that have connections to the cerebellum, they might have incoordination, ataxia.

I have one patient whose first symptom was complaining that she lost her own autobiographical memory. She couldn’t remember parts of her own life. This was 20 years ago. She went right to the psychotic psychiatric ward. Then about a week later she started to develop other symptoms that made us realize this was a neurologic problem, not psychiatric. At that point we did a brain MRI. We saw the classic features of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease and we had our diagnosis. Unfortunately she died within a few weeks.

Being Patient: What is the prevalence of RPD?

Dr. Michael Geschwind: Unknown. At our center, we specialize in cognitive impairment and dementia. We also see a lot of movement disorders usually associated with cognitive impairment. We found that between between two and three percent of all the cases referred to us with cognitive impairment were actually rapidly progressive.

Being Patient: What is the lifespan of patients with RPDs?

Dr. Michael Geschwind: It’s all very varied. Let’s talk about CJD for example. The shortest I’ve seen is two weeks from onset to death. I’ve followed other patients for eight years with CJD. Now, the last probably six years of their life was in pretty much a persistent vegetative state. It wasn’t a quality of life, but it took two years to get to that point.

Typically for CDJ in the literature, the median survival is about four to seven months, so about half the patients will live less than that and half will live longer than that. 90 percent of patients in the literature live less than a year.

In my own cohort. I find it’s a little longer: 90 percent of patients will probably live less than a year and a half. That’s why it’s really important to make a diagnosis quickly and correctly because you don’t want to give somebody a wrong diagnosis if it’s in fact something treatable or reversible if you catch it quickly enough. You don’t want to tell somebody they have CJD when they have a treatable autoimmune disorder, which is why there are things that can help us differentiate between these diseases. It takes clinical experience but often we can tell. There are certain features that are more common in CJD and less common in autoimmune diseases, and vice versa.

Being Patient: Can RPD occur at any age?

Dr. Michael Geschwind: Yes, they can occur at any age. We have some of the autoimmune causes in six-month-old babies and yet, we have autoimmune causes in people who are 90 years old. For CJD, the youngest sporadic patient I’m aware of is 12 years old, the oldest is 96. But the peak age is in the early 60s. That’s the most common age for CJD and probably for most rapidly progressive dementias. But I have patients in their 20s, 30s. When they’re that young, often it’s a genetic disorder, an inborn error of metabolism. They can be a little harder to diagnose. Sometimes we have to do more complicated, urine, blood, spinal fluid analyses to detect inborn errors of metabolism.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Contact Nicholas Chan at nicholas@beingpatient.com

what vitamins and minerals or herbs are helpful for dementia. Have been using lions mane for a while. please answer. thank you

Why was there no mention of Lewy Body Dementia? This is the number two in the dementia umbrella and has been called THE WORST OF ALL THE DEMENTIAS, yet gets very little, of any, in these type of articles. As A person with LBD, I find it inconsiderate, unprofessional, and personally insulting to all who suffer from LBD!

Hi William,

We have a lot of coverage on Lewy Body dementia. If you go to https://www.beingpatient.com Here is where you can find some of our coverage: https://www.beingpatient.com/?s=lewy+body&asp_active=1&p_asid=3&p_asp_data=1¤t_page_id=5942&qtranslate_lang=0&filters_changed=0&filters_initial=1&asp_gen%5B%5D=title&asp_gen%5B%5D=content&asp_gen%5B%5D=excerpt&customset%5B%5D=post&customset%5B%5D=voice