Targeting beta-amyloid protein before symptoms of cognitive decline or Alzheimer’s appear may be the key to slowing down the disease, researchers say.

Targeting beta-amyloid protein before symptoms of cognitive decline or Alzheimer’s appear is the goal of one trial out of the National Institute on Aging (NIA), which recently released its first data set from its prevention trial. The Anti-Amyloid Treatment in Asymptomatic Alzheimer’s Disease (A4) study is testing a drug called solanezumab, which aims to slow down cognitive decline before Alzheimer’s symptoms appear by targeting amyloid. The new data shows that elevated levels of amyloid in the brain is a sign of the early stage of Alzheimer’s, and that it’s associated with family history of the disease and lower cognitive test scores.

Plenty of past trials have examined different drugs in their effectiveness in fighting amyloid. Many have failed, leading Alzheimer’s researchers to question in recent years whether the “amyloid hypothesis” is indeed correct.

But researchers working on the A4 study believe that the problem with the past failed drugs is that they started too late, well after amyloid had already built up in the brain. It’s targeting amyloid in the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s that may hold the key, they argue.

“A major issue for amyloid-targeting Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials, and one that is being addressed with the A4 study, is that previous trials may have been intervening too late in the disease process to be effective,” Dr. Richard Hodes, NIA Director, said in a news release.

“A4 is pioneering in the field because it targets amyloid accumulation in older adults at risk for developing dementia before the onset of symptoms,” he added.

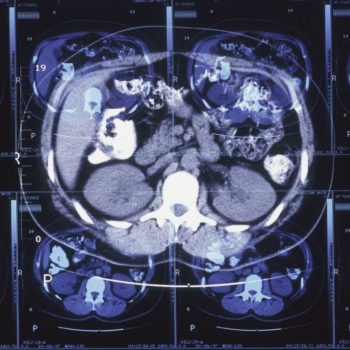

In the latest data, the A4 researchers examined 15,000 cognitively normal people and parsed those down to some 4,486 participants to measure amyloid in the brain through PET scans. Of that group, some 1,323 participants showed elevated levels of amyloid. The goal was to hone in on people who weren’t showing cognitive decline yet—but who had amyloid building up in their brains already.

“A4 demonstrates that prevention trials can enroll high risk individuals—people with biomarkers for Alzheimer’s who are cognitively normal,” Laurie Ryan, chief of the Dementias of Aging branch at NIA’s Division of Neuroscience, said in the news release.

“Ultimately, precision medicine approaches will be essential,” she continued. “Alzheimer’s disease is never going to have a one-size-fits-all treatment. We’re likely to need different treatments, even combinations of therapies, for different individuals based on their risk factors.”

When it comes to drugs fighting amyloid, though many trials have failed, Biogen’s aducanumab made headlines in 2019 when it was resurrected after showing efficacy in reducing cognitive decline. The new clinical trial recently began and the first participant received a dose in March.

Another trial at the University of Southern California (USC) is testing a drug called BAN2401, which is an antibody that sticks to amyloid in the brain, to see if it can fight Alzheimer’s in the earliest stages, before symptoms develop.