In a decade-long clinical trial, Eli Lilly’s Alzheimer's drug solanezumab failed to hit its benchmarks in slowing cognitive decline.

Recently, Eli Lilly announced that their anti-amyloid drug solanezumab failed to prevent Alzheimer’s in cognitively healthy older individuals who showed amyloid plaque accumulation in their brain, over the course of its 10-year-long trial (called the A4 study).

More than 99 percent of Alzheimer’s drugs fail out of clinical trials. Only two of these drugs have succeeded so far: Aduhelm (aducanumab) and Leqembi (lecanemab). (In February 2024, Biogen took Aduhelm off the market indefinitely.) These drugs, like many others in trials now, are designed to slow cognitive decline by targeting toxic beta-amyloid plaques in the brain. But the jury is still out on whether they are yielding meaningful clinical improvements for patients. Rather than targeting plaques like Aduhelm or Lecanemab, solanezumab was designed to clear a smaller, small free-floating soluble form of beta-amyloid called Aβ42. It is believed that Aβ42 is a key component of amyloid plaques, so reducing Aβ42 would prevent plaque formation.

“The A4 Study concludes our clinical development of solanezumab and indicates that targeting soluble amyloid beta through this mechanism is not effective in this population,” said John Sims, head of medical, global brand development for solanezumab, at Eli Lilly and Company in a company press release. “While this study was negative, the unique data generated have increased our understanding of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease and will advance the next generation of Alzheimer’s Disease prevention studies.”

The study launched in 2013, enrolling a total of 1,100 cognitively healthy individuals aged 65 to 85 who showed amyloid plaque accumulation in the brain. The participants were randomized to either receive solanezumab infusions or placebo over the course of 4.5 years. Regardless of treatment group, the individuals in the study experienced cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s progression at the same rate. Higher levels of beta-amyloid plaques measured at the start of the study were associated with a greater risk of progression to Alzheimer’s.

Expert reactions to the data

Dr. Reisa Sperling, a neurologist at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital at Harvard Medical School and the A4 trial’s director, believes the negative findings support the idea that amyloid plaques are causing Alzheimer’s.

“These findings indicate that amyloid is a key driver of cognitive decline at the preclinical stage of Alzheimer’s disease,” said Reisa Sperling, M.D., a neurologist at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School and the trial’s director. “Solanezumab did not substantially impact amyloid plaque burden in the brain, and unfortunately did not slow cognitive decline. These data suggest that we may need to be more aggressive with amyloid removal even at this very early stage of disease.”

Dr. Alberto Espay, the study’s senior author and professor of neurology at the University of Cincinnati, who was not involved with the study disagreed, writing that the study does not support the amyloid hypothesis. Removing the precursor to amyloid plaques, Aβ42, did not stop new plaques from forming or the disease from progressing — suggesting that the amyloid plaques are not the sole cause of Alzheimer’s progression.

What’s next?

Eli Lilly is currently testing two other anti-amyloid drugs in Phase 3 clinical trials, both of which target the plaques themselves.

Donanemab has completed Phase 2 trials but the FDA declined to grant it an accelerated approval based on those results. If Lilly’s Phase 3 trial data shows the drug is safe and effective, the company will apply for donanemab’s FDA approval “shortly thereafter.” Trials are expected to be completed by 2027.

Remternetug — which Eli Lilly’s executives have dubbed the “next generation” of anti-amyloids — is currently recruiting 600 participants in the early stages of cognitive decline who test positive for beta-amyloid.

One of the unique aspects of the trial is how the drug will be delivered. Trial participants will be randomized across two groups, where one will receive intravenous infusions, while the other group will receive injections just under the skin. This will give researchers new insight into whether one delivery method or another is more effective. The results from this trial are expected by 2025.

Like Biogen and Eisai, Eli Lilly’s has gone all in on the anti-amyloid plaque strategy for treating Alzheimer’s.

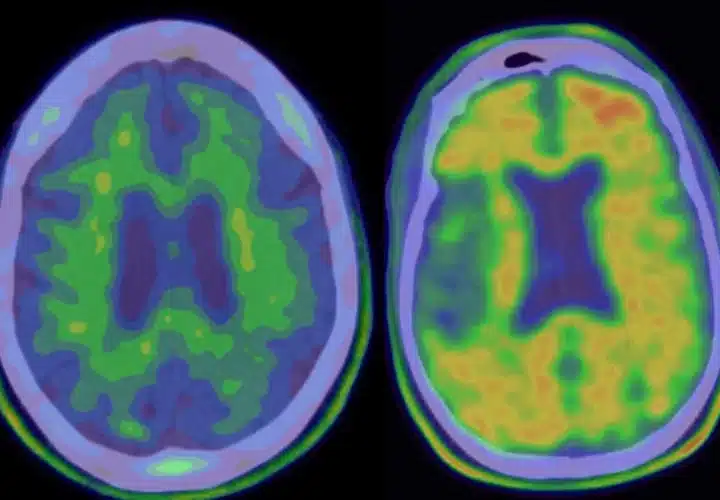

Image: A PET scan of a brain that is negative for Alzheimer’s disease pathology; a scan of brain with beta-amyloid build-up, which would be eligible for solanezumab trial. Columbia University Medical Center.

UPDATE: 3 March 2024, 9:21 P.M. ET. In February 2024, Biogen took Aduhelm off the market, citing financial concerns. Although the drug did receive accelerated, conditional FDA approval for the treatment of early Alzheimer’s disease in 2021, it is no longer available to new patients. The company announced it would sunset trials in May 2024 and cease supplying the drug to current patients in November 2024.