Scientists still don’t know what causes Alzheimer’s, but they do have one, long-standing theory: the amyloid hypothesis. Some say it’s on the brink of being proven. Others say it’s “too big to fail.”

Want to start a ruckus in a room full of neuroscientists? Just yell: “The Alzheimer’s amyloid hypothesis has been proven!”

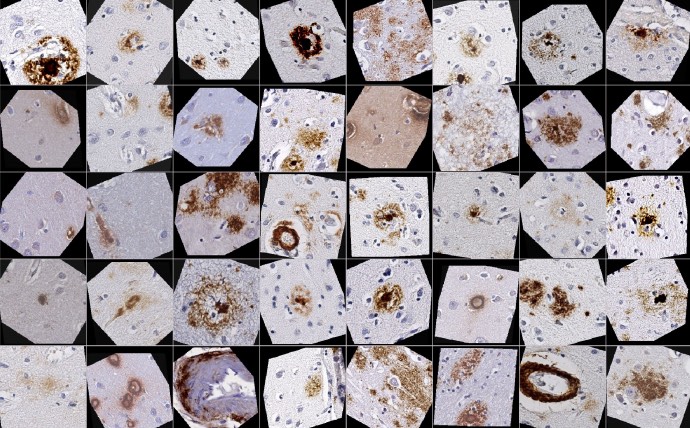

You’ve probably heard about beta-amyloid, a protein that builds up into a plaque, clogging up the brains of people living with Alzheimer’s disease. This association between the plaque build-up and the disease is well founded. But when this association is called the definitive cause of Alzheimer’s, that’s when some neuroscientists start to squirm.

In the brains of people with Alzheimer’s, amyloid protein is known to clump together in plaques, eventually leading to cognitive symptoms like impaired memory and other problems. According to the “amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s,” this process is the root cause of the disease. And for the past three decades, that has been the leading theory. But what if these protein clumps are not the cause — what if they’re just another symptom of a cause that scientists still have yet to pinpoint?

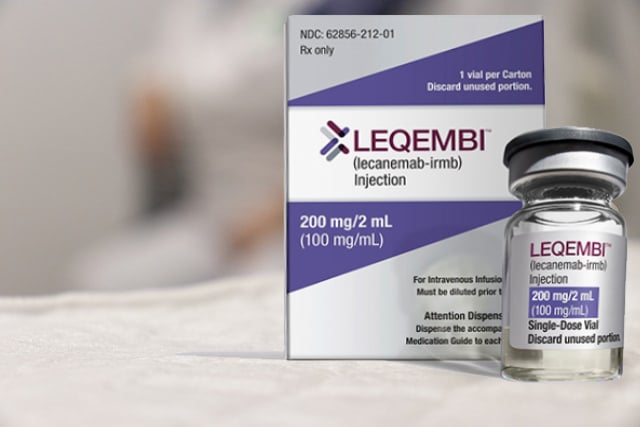

Some scientists, like Marwan Sabbagh, a clinician and professor of neurology at the Barrow Neurological Institute who was involved in the trials for newly FDA-approved anti-amyloid Alzheimer’s drug Leqembi, are certain that amyloid plaques play a major causative role in Alzheimer’s. Case in point:. This camp says effectively targeting the protein clumps early enough should stop the disease in its tracks.

Others, like Ruth Ithzaki, a leading researcher on the link between viruses and Alzheimer’s, say it’s time to set amyloid aside and look to other possibilities. Yet other researchers, like clinician Alberto Espay and scientist Bruno Imbimbo, are skeptical that removing amyloid plaques will stop the disease. While they don’t completely disregard amyloid, they believe that the key to protecting the brain is raising the levels of a form of beta-amyloid that does not form plaques.

Here’s an in-depth look at how this debate is playing out.

Affirmation in anti-amyloids

After decades of mixed results, the amyloid hypothesis does have some new marks in its favor: In the past two and a half years, two new drugs for Alzheimer’s — the first disease-modifying interventions ever approved — hit the market.

“The question isn’t whether amyloid is relevant, the question is, are we treating it too late,” Sabbagh said.

In clinical trials, Leqembi was shown to be effective in improving cognitive function and slowing cognitive decline by at least a small amount. Aduhelm, approved by the FDA two years earlier, was also designed to slow cognitive decline caused by early-stage Alzheimer’s, though there is some dispute as to its efficacy.

Is the approval of these two anti-amyloid drugs for Alzheimer’s enough to vindicate the amyloid hypothesis?

Sabbagh says yes: “The field is energized by the new findings” behind the Leqembi trial. Given the positive results from the Phase 3 Leqembi trial, “People who question the amyloid hypothesis are not spending their day job deep in the weeds” of Alzheimer’s drug development and clinical trial data, he said.

With the certainty of amyloid plaques as a cause established, Sabbagh believes that “the real question then is, are we treating [Alzheimer’s] too late?”

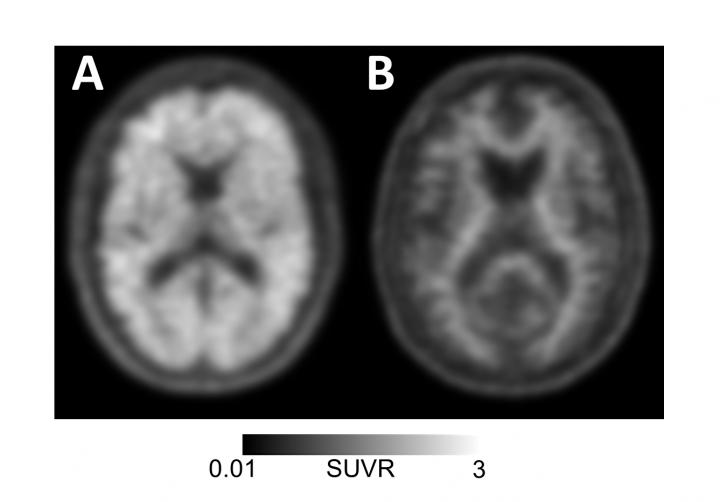

He points out that a lot of the “amyloid accumulation is prior to the onset of memory symptoms.”

(In February 2024, Biogen took Aduhelm off the market indefinitely.)

This idea is supported when comparing different anti-amyloid trials against each other. Sabbagh compared the Leqembi trial to the failed gantenerumab trial. The patients in the Leqembi trial had lower levels of amyloid and more patients with mild cognitive impairment, which may be why it succeeded where gantenerumab failed.

But not all researchers are as convinced as Sabbagh that the Leqembi results are so compelling. Scientists have tested the amyloid hypothesis which has failed over and over in clinical trials. If all of these drugs designed to stop Alzheimer’s through the same mechanism failed, it is an indictment of the amyloid hypothesis regardless of one successful trial.

In fact, almost all 40 of the drugs developed to clear amyloid plaques have failed clinical trials — from avagacestat, to gantenerumab, to solanezumab to verubecestat. The most recent addition to the list is drugmaker Roche’s crenezumab, which failed to slow cognitive decline after a lengthy nine year-long trial. The results are still out on Eli Lilly’s donanemab, currently in Phase 3 trials.

‘Too big to fail’

Scientists working on the amyloid hypothesis have “been working in the field so long that they don’t want to get amyloid pushed out of the picture,” University of Manchester emeritus neuroscience professor Ruth Itzhaki told Being Patient.

Espay agreed that part of the attachment to the concept of amyloid as Alzheimer’s disease’s root cause is just a matter of investment.

“This hypothesis is ‘too big to fail,’” said Espay.

With three decades of research into amyloid, and few positive clinical trials to show for it, he said, this deeply entrenched theory “has sucked most oxygen from competing ideas.”

Increasingly, Alzheimer’s experts are making the case that the focus on amyloid has detracted from research into other potential causes — from neuroinflammation to metabolism Itzhaki’s focus, the Herpes-Simplex Viruses. “The virus gets to the brain in middle age, and then establishes itself, causing lesions (degeneration),” she said. “Every so often events such as stress, infection, and immunosuppression reactivate [the virus] and then recurrent events lead to development in the accumulation of damage.”

Bruno Imbimbo, a researcher and Alzheimer’s drug developer at the pharmaceutical company Chiesi Farmaceutici, says genetic pathways also deserve more research investment.

“I believe that the amyloid hypothesis has diverged funding from other interesting biological targets like the ApoE4 pathway,” he told Being Patient.

A parallel hypothesis: Not all amyloid is bad

There are many different “species” of amyloid proteins. The drug Leqembi targets a sticky, misfolded form that accumulates in plaques. Earlier on however, beta-amyloid proteins are soluble in the brain, meaning that they “dissolve” like sugar or salt in water. There is mounting evidence that this smaller, soluble-form of amyloid is actually beneficial for brain health.

Alberto Espay, a professor and clinician at the University of Cincinnati School of Medicine, for one, doesn’t believe that the published results from the Phase 3 Leqembi trial necessarily support the idea that the amyloid plaques are responsible for Alzheimer’s. Instead, it may be the measured increase in small soluble forms of beta-amyloid called Aβ42 was associated with cognitive improvements, rather than clearance of the plaques themselves.

“Aβ42 [a soluble beta-amyloid] increases [in the Leqembi trial], which is unexpected since this is not the objective of anti-amyloid treatments,” Espay said. “I think the field might not turn around until we have more than the data so far shared, which so clearly shows that low [levels of] soluble Aβ42 is detrimental whereas high [levels] Aβ42 is protective.”

Meanwhile, Imbimbo and Espay are both part of a camp of researchers who theorize that drugs like Leqembi might appear to work not because they get rid of amyloid plaques in the brain (which are composed of multiple units of smaller beta-amyloid proteins stuck together), but because they break it up into Aβ42 which may protect the brain and boost cognition. Espay has published studies supporting the idea. “We showed that the levels of Aβ42 above 800 pg/ml were associated with normal cognition regardless of increasing brain amyloid burden,” he said.

Some research has found that beta-amyloid may help protect the brain from stress or inflammation. When this particular type of beta-amyloid protein tics together and forms amyloid plaques, they are no longer able to do their job.

What does all this mean for future anti-amyloid drugs in the drug development pipeline?

Espay argues that because of the 40 or so failed trials, it is unlikely that amyloid plaques are the disease’s actual (and yet unknown) root cause, meaning they’re unlikely to be totally effective. Further, any successful results could be explained away and attributed to an increase in Aβ42. In October 2022, he published a commentary alongside Timothy Daly, a professor at Sorbonne University and Karl Herrup, a clinician-scientist at the University of Pittsburgh, arguing that it is unethical to keep testing these therapies because of the risk to participants.

“The Alzheimer’s research field must take stock and prioritize the wellbeing of people we ask to participate in our trials, and worry less about pet theories and stock portfolios,” Espay and Daly wrote in the op-ed. “This is particularly important given the personal costs endured by early-stage patients and families when hype around new drugs based on preliminary results of early trials becomes hope, later dashed by results of more definitive controlled trials.”

What’s next for Alzheimer’s treatments?

With the success of Leqembi, Sabbagh foresees that it will lead to big changes in treatment: “I think these next few years will lead to a radical change in how we practice medicine.” He believes that the Alzheimer’s field will continue its focus on anti-amyloid therapies.

The approval of Leqembi and other anti-amyloid allows clinics to get “more clinical experience post-approval on how to use these drugs [in a medical setting],” he said, adding that in the future blood biomarkers will be incorporated to allow for even earlier testing and treatment.

“I think the field might not turn around until we have more than the data so far shared,” Espay said. His research shows that low levels of non-clumping soluble beta-amyloid — small bits of these proteins that don’t form plaques — is detrimental while high levels are protective.

UPDATE: 3 March 2024, 9:20 P.M. ET. In February 2024, Biogen took Aduhelm off the market, citing financial concerns. Although the drug did receive accelerated, conditional FDA approval for the treatment of early Alzheimer’s disease in 2021, it is no longer available to new patients. The company announced it would sunset trials in May 2024 and cease supplying the drug to current patients in November 2024.