UPDATE, 7 July 2023: Lecanemab has received full, traditional approval from the FDA and is on the market as Leqembi. Medicare coverage will soon be made available for the drug, according to the CMS.

Lecanemab, Eisai and Biogen’s experimental anti-amyloid Alzheimer’s drug, which recently wrapped its Phase 3 clinical trials, continues to make the news. Some of these headlines discuss the deaths of clinical trial participants who were taking the drug. So, how safe is the drug, and how do the benefits for people living with Alzheimer’s disease stand up to the risks?

Here’s a little background: In early December 2022, at the annual Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease (CTAD) conference on Alzheimer’s research, Eisai and Biogen presented data about their monoclonal anti-amyloid drug lecanemab, concurrently publishing the results in the New England Journal of Medicine. The trial showed that lecanemab slowed the rate of cognitive decline in people with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia.

“They’ve been successful when others have not, with how a company should approach disease modification trials.” said Sharon Rogers, CEO of AmyriAD who led the development of the cholinesterase inhibitor donepezil (Aricept) while at Eisai in the 1990s.

The key findings of the trial, lecanemab slowed cognitive decline by 27 percent. This is repeated over and over again across different media outlets after the presentation at CTAD. From the sounds of it, 27 percent seems like a lot. But what does “slowing cognitive decline by 27 percent” actually mean for an individual living with Alzheimer’s?

“What is underreported in the press discussions is that both treatment and control groups declined, and it was just slower with the drug,” Karl Herrup, an Alzheimer’s researcher at the University of Pittsburgh, told Being Patient.

In the lecanemab trial, participants in both the control and lecanemab group started off scoring 3.2 out of a total of 18 points on the Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB) scale. This is a validated measure of cognitive decline where larger numbers indicate more impairment. During the trial, both the placebo and treatment groups experienced cognitive decline over the course of 18 months. At the end of the trial, the lecanemab group declined 1.21 points down to a score of 4.41 while the placebo group declined 1.66 points to 4.86.

This means that the participants that received lecanemab had a slower rate of decline over 18 months by 0.45 points. This is equivalent to slowing cognitive decline by 27 percent. For reference, a score between 3.0 and 4.0 indicates very mild dementia while a score between 4.5 and 9.0 indicates mild dementia.

Another way to think about the results is to compare them to the effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors like donepezil (Aricept). It is estimated that people taking the drug compared to a placebo group may slow their cognitive decline by 0.6 points over the course of 12 months.

Are the lecanemab findings clinically meaningful for individual patients?

Being Patient asked Eisai to explain whether their results were clinically meaningful — whether they would actually make a difference in an individual patient’s life.

“The degree of worsening in daily functioning and cognition experienced by an individual in the placebo group at 18 months might not be experienced by an individual treated with lecanemab until almost 7 months later,” a spokesperson told Being Patient. “Essentially, 0.5 represents clinically notable decline in a key domain of Alzheimer’s Disease symptomatology by physicians and care-partners.”

Some advocacy groups, including the Alzheimer’s Association, also made definitive statements emphasizing that “lecanemab will provide patients more time to participate in daily life and live independently” in a written statement. “It could mean many months more of recognizing their spouse, children and grandchildren.”

But what do scientists unaffiliated with the trials say about this important question?

Some researchers believe lecanemab will make a small but meaningful difference for people with Alzheimer’s disease.

Rogers explained that the results showed a six month slowing in the progression of mild-cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer’s. This could potentially slow the course of the disease by months, delaying the later stages of dementia.

The image below, modified from Eisai’s press release, shows that we can draw a horizontal line between the lecanemab datapoint at 18 months and the placebo data point at 12 months. On the graph, this indicates that the changes in cognition between these two data points are equivalent.

John Hardy and Bart De Strooper, professors working at the UK Dementia Research Institute at University College London called the trial “impressive” and “remarkable” in comments provided to the Science Media Center. However, neither researcher discussed the clinical significance of the findings in their comments.

Other researchers believe the meaning of the difference lecanemab will make for Alzheimer’s patients is still unclear.

“It is difficult to know if this will be noticeable for patients and their families,” Donald Weaver, a clinician and senior scientist at the Krembil Research Institute told Being Patient. He was uncertain whether the results would be clinically significant but added that “some families would argue that even a day or two would be progress.”

Tara Spires-Jones, a professor involved in the UK Dementia Research Institute at the University of Edinburgh, also provided a comment to the Science Media Center. “There is not an accepted definition of clinically meaningful effects in the cognitive test they used, and it is not clear yet whether the modest reduction in decline will make a big difference to people living with dementia.”

Similarly, Nick Fox who is the director at University College London’s Dementia Research Center wrote that he was unsure whether slowing the disease 27 percent was meaningful.

“A really key question is whether clinical benefits are progressive, if they continue beyond the 18 months, if they are sustained and cumulative.”

Yet other scientists believe the the difference in cognition that lecanemab will bring about is not clinically meaningful for patients.

Rob Howard, professor of old age psychiatry at University College London Institute of Mental Health is among them. “This is below what is considered the minimum clinically important difference of 1.0 point,” Howard wrote to Being Patient. “So, it isn’t clinically significant or noticeable in an individual patient.” He added that he does not believe the cognitive benefits outweigh the risks and was unconvinced by some of the analysis predicting patients’ response past 18 months.

“If you set the bar low enough, you can achieve almost anything,” Herrup said, referring to the trial’s success. “Everything I know suggests that that slowing is probably undetectable by the patient or their families,” Herrup said. Though he is a skeptic of the amyloid hypothesis, he did note that removing amyloid plaques with lecanemab provided some evidence linking it to cognition.

Matthew Schrag, a clinician-scientist at Vanderbilt University said: “I doubt that most individual patients would be able to detect this difference.”

These positions are supported by a 2019 study that asked when these results are clinically meaningful. The authors suggested that a minimum difference of 0.98 is noticeable for those with mild cognitive impairment while for mild Alzheimer’s, the clinically meaningful threshold is closer to 1.6 points.

A Lancet editorial written by a commission of prominent Alzheimer’s researchers also raised these concerns. They also cautioned that adverse events seen in more than one if five patients taking on lecanemab could accidentally unblind participants in the trial. Since they may know that they are getting a treatment, it introduces additional bias into the results. The authors emphasized that “the immediate impact of lecanemab should not be overstated.”

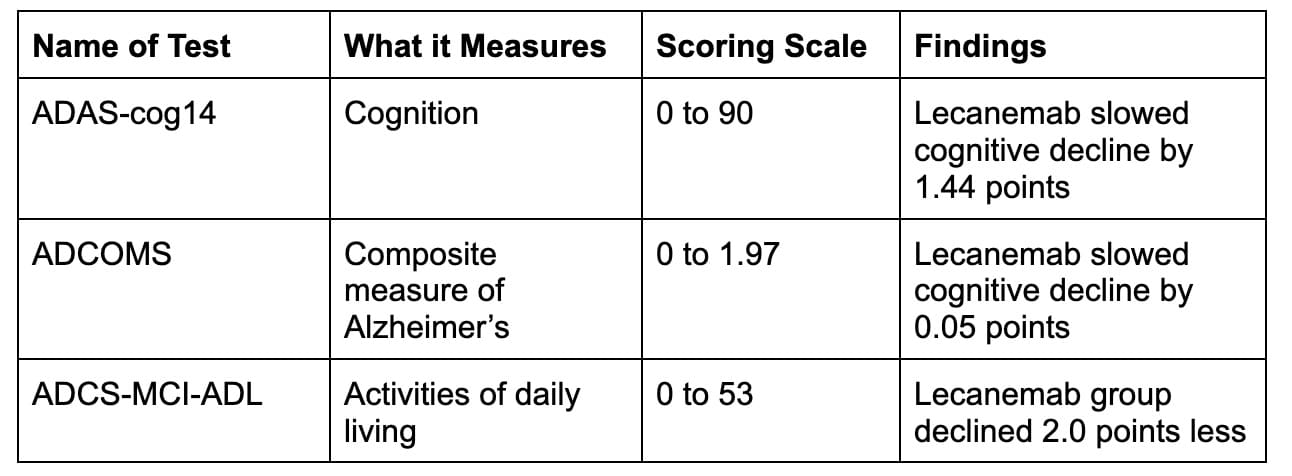

What else did the trial show?

The trial also took several other measures of cognition. Here is a quick summary of those findings.

The trial also found that lecanemab led to a significant reduction in brain amyloid compared to placebo, where the levels of brain amyloid remained high. The average reduction in brain amyloid moved lecanemab patients below the threshold of a positive amyloid PET scan.

The researchers also performed some exploratory analysis to understand whether some groups benefited more from lecanemab. Though the sample was small, the researchers found that people with two copies of the ApoE4 gene and received lecanemab actually showed faster rates of cognitive decline than carriers assigned to the placebo group. Although women are more likely to develop Alzheimer’s, they benefited substantially less from lecanemab than the men.

How safe is lecanemab?

Serious adverse events occurred in 14 percent of people receiving lecanemab and 11.3 percent in the placebo group. In addition, 6.9 percent of people in the lecanemab group left the study due to the side effects compared to 2.9 percent in the placebo group.

More than one in four people in the lecanemab group received an infusion-related reaction compared to less than one in thirteen people in the placebo group.

But the biggest flurry of discussion about lecanemab’s safety in the media has revolved around deaths that occurred among participants during the drug’s clinical trial.

Prior to the presentation at CTAD, STAT News and Science reported on two deaths linked to lecanemab. These deaths occurred in the open-label extension of the study, where some participants were observed as they continued taking lecanemab after the 18-month randomized Phase 3 trial concluded.

Eisai did not attribute the deaths to lecanemab. “The two cases on lecanemab occurred in the open-label extension study,” an Eisai spokesperson told Being Patient. “Both cases had significant comorbidities and risk factors including anticoagulation contributing to macrohemorrhage or death.”

A third death occurred during open-label extension in mid-September that was not discussed at CTAD. The media learned abotu this death in December 2022.

According to reporting by Science, the woman who died had no other underlying medical issues. Regarding this third death, Eisai shared comments with Science magazine and Being Patient.

“As a general comment on the unfortunate occurrences of participants in clinical trials who pass away, any evaluation of a death, or deaths, must consider the age of the population and their other medical conditions as well as the length of the study.],” a spokesperson for Eisai wrote.

“The rates of deaths and causes of deaths that we are observing in the lecanemab studies are consistent with those expected in people this age as well as what was observed in our long-term ARICEPT experience,” the spokesperson added. “Of course, the best source of information is the double-blind placebo-controlled studies, which were presented at CTAD and in the NEJM publication. The reports of deaths in the lecanemab treated patients is similar to the placebo group and does not suggest an increase in deaths overall or from any individual cause.”

The details regarding the cause of the individual deaths during the trial was not shared in the publication or in the conference making it difficult for scientists who aren’t involved in the trial to make any other determination about lecanemab-related deaths versus other causes.

Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities

Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) are a side effect of experimental anti-amyloid treatments. While they are usually asymptomatic, it is unclear whether ARIA is associated with harmful outcomes in the long-run.

Around one in eight people who received lecanemab experienced ARIA-E which refers to swelling of the brain. Among them, only 3 percent were symptomatic. One in seven participants developed ARIA-H which refers to brain bleeding. These reactions occurred most often in participants who carried two copies of the ApoE4 gene.

Do the benefits outweigh the risks?

Do Leqembi’s risks to a patient outweigh its cognitive health benefits? This is the million-dollar question that patients and caregivers must consider if the drug becomes available.

An Eisai spokesperson did not answer the question directly, writing that the company “believes this evidence is sufficient to obtain traditional approval” and that they will review the findings with the FDA by the end of the year.

Many of the scientific experts that provided comments to the Science Media Center did not explicitly state whether the benefits outweigh the risks. Instead, they mentioned that rigorous monitoring and further study of who is at risk of developing serious side effects is required. Those that did weigh in clearly did not believe the benefits outweighed the risks.

Rogers believes that if the drug is approved, the decision to take the drug will be individual. In addition, she believes it is important for emergency physicians treating stroke patients to know whether they are currently taking or have taken anti-amyloid monoclonal antibody drugs in the past. It may require strokes to be treated differently than usual.

“I would say to a patient group that I recommend against it,” Herrup said. He added that we don’t know the long term impact of ARIA. He worries that the price point may create more disparities in treatment.

“This is still a relatively small trial, so it is going to take additional trials with more patients to settle the issue of whether the benefits outweigh the risks,” Weaver said. “Additional use of the agent for longer periods of time will be crucial before any definitive conclusions can be reached regarding the ultimate safety and use of this agent.”

Howard also does not think that the benefits outweigh the risks, even though lecanemab may be safer than Aduhelm. (In February 2024, Biogen took Aduhelm off the market indefinitely.) Similarly, Schrag was concerned about the drug’s safety profile, believing it “washes out any marginal cognitive benefits.”

Answering the other frequently asked questions about lecanemab

If you’re just catching the news about lecanemab, or need a quick reminder, we answer some of the other questions people frequently ask about the drug.

Was lecanemab tested across all stages of Alzheimer’s disease?

The clinical trial tested lecanemab in people who had amyloid plaques in their brain and were diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment or mild Alzheimer’s disease.

What kind of drug is lecanemab?

Lecanemab isn’t like the drugs you might keep in your bathroom cabinet. It is an antibody created by scientists to target a specific type of toxic amyloid protein. Since it “sticks” to one particular spot on the amyloid, it is called monoclonal.

How is lecanemab administered?

Lecanemab is delivered intravenously to patients, via an infusion. This requires a specialty facility and staff to oversee the process and ensure patient safety.

What’s the difference between Leqembi and Aduhelm?

Aduhelm targets beta-amyloid plaques for clearance while lecanemab targets toxic beta-amyloid proteins before they form plaques.

What happens when people stop taking a monoclonal antibody anti-amyloid drug for Alzheimer’s like Leqembi?

According to the data, amyloid plaques are cleared below the Alzheimer’s threshold after 18 months. An Eisai spokesperson explained that participants who discontinued lecanemab after 18 months in their open label study experienced a gradual accumulation of beta-amyloid and decline similar to what the untreated group experienced.

“Continued treatment is required, although we are exploring less frequent maintenance dosing after amyloid clearance,” the spokesperson added.

The takeaway on Leqembi (lecanemab)

While experts think it is likely that lecanemab is approved by the FDA, few experts have stated that the benefits unequivocally outweigh the risks. The majority of scientists Being Patient interviewed who weren’t involved in the clinical trial either don’t think the results are clinically meaningful or unsure. Many of them worry about the adverse effects and some bring up the possibility of bias in the clinical trial.

We will continue to provide updates as we receive comments from other experts.

UPDATE: 3 March 2024, 9:21 P.M. ET. In February 2024, Biogen took Aduhelm off the market, citing financial concerns. Although the drug did receive accelerated, conditional FDA approval for the treatment of early Alzheimer’s disease in 2021, it is no longer available to new patients. The company announced it would sunset trials in May 2024 and cease supplying the drug to current patients in November 2024.