Science-backed information on the where, when and how of mid-stage dementia — along with expert-backed caregiver guidance for dementia's middle stages.

Dementia progresses in stages. Alzheimer’s disease, for example, is considered to have seven distinct stages, delineated by the areas of the brain the disease affects. But the progression of dementia is often unpredictable, and people’s symptoms can ebb and flow. To keep things simple, most people talk about dementia overall as having three stages: early-stage, middle and late-stage dementia. Clinicians can distinguish the different stages of dementia, identifying the common symptoms that characterize each phase, which helps people living with dementia and their loved ones plan ahead.

What is middle-stage dementia like?

Dementia is a complex illness — one that is often misunderstood. The person’s age at the time of diagnosis, the severity of the symptoms and nature of its progression vary from one person to another, but dementia is often thought of as a condition that only affects older adults, one that strips people of their day-to-day abilities shortly after a diagnosis. Misconceptions of dementia, however, are stigmatizing for those living with the illness.

As people living with dementia will tell you, it is often assumed that people with dementia are, by default, in the late stages of the illness — wheelchair-bound or bed-bound, disoriented and unable to recognize loved ones. This is true of dementia’s late or end stages, but certainly not for the majority of people the majority of time in early and in middle-stage dementia.

Middle-stage dementia, in particular, is usually the start of physical and cognitive functioning changes that significantly impact a person’s ability to perform everyday tasks without assistance and quality of life. Although moving from one stage to the next signals deteriorating cognitive functioning, and each stage comes with new and worsening symptoms, as well as personality and behavioral changes, people in middle-stage dementia experience emotions like anyone else, and social interactions and friendships are more important than ever.

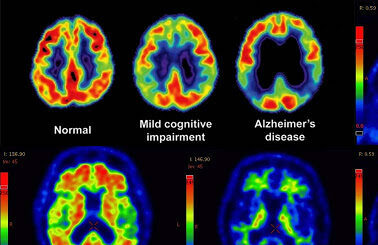

What happens in the brain in middle-stage dementia?

In the middle stage of dementia, persistent and continuous brain changes affecting memory, thinking, emotions, and behavior may result in dementia symptoms becoming more noticeable and disruptive to normal functioning. For instance, if a person could go about with daily activities like shopping or getting dressed by themselves in their early stages, they may lose this ability and require help from others.

Caregiving may become more demanding, and caregivers may need to intensify monitoring, support, and care for people in this stage by hiring professional services for in-home care and getting assistive devices like GPS trackers.

Dr. Zaldy Tan told Being Patient that people living with dementia and their caregivers can ask their doctor what stage of dementia they or their loved one is in. The doctor may confirm the dementia stage by evaluating symptoms.

When does mid-stage dementia occur?

Generalizing about what stage a person living with dementia will be in at any given point after their diagnosis is tough: For one thing, different types of dementia progress at different rates. For example, while people with Alzheimer’s typically experience a slow progression of the disease, and might live a relatively “normal” life for years or decades after a diagnosis without symptoms becoming debilitating, vascular dementia — which tends to cause mini-strokes — may lead to a more rapid pace of cognitive and motor decline.

Other factors can play into this rate of decline as well: The cognitive symptoms of people with dementia who are hospitalized may deteriorate more quickly than expected. And during the COVID-19 pandemic, many families report a more rapid decline in loved ones, which has been linked to increased stress and to isolation — a risk factor for brain health.

Is the middle stage of dementia the longest phase?

How long can a person live with middle-stage dementia? Again, every person’s case is unique, and some may progress faster than others into the late or final stages of dementia. But in many cases, the middle stage of dementia is the longest phase in the course of this condition. It may last for years.

How do you know what stage of dementia you’re in?

In an expert LiveTalk on the stages of dementia, Dr. Zaldy Tan, director of the Cedars-Sinai Health System’s Memory and Aging Program and medical director of the Jona Goldrich Center for Alzheimer’s, urged people living with dementia and their caregivers to ask their doctors the question, “What stage of dementia am I or my loved one in?”

According to Zan, understanding the stage of one’s dementia progression starts the conversation between patients, families and doctors to plan for treatment, day-to-day needs and care services appropriate for the person’s specific stage of dementia. To help doctors help them, Tan said, caregivers will want to describe in detail about the symptoms they have observed in the person they are caring for, providing clues for the clinician to determine the stage of dementia. What are some of these symptoms?

What are the typical symptoms of middle-stage dementia?

Middle-stage dementia is usually accompanied by behavioral and psychological symptoms that significantly interfere with daily functioning and may cause distress to people with dementia and their loved ones. Some of these symptoms and behavioral changes include:

- Forgetfulness and memory loss

- Confusion

- Trouble organizing and planning

- Difficulty following instructions

- Difficulty recognizing family members and friends

- Difficulty adapting to new environments and situations

- Difficulty reasoning

- Difficulty with language

- Difficulty reading, writing, and working with numbers

- Social withdrawal and apathy

- Sleep and appetite changes, including sundowning

- Mood swings

- Impulsive behavior

- Wandering

- Restlessness

- Anxiety

- Hallucinations, delusions, and paranoia

- Repetitive behavior — repetitive movements or speech

- Agitation, which might involve aggression, and potentially physical acting out or yelling

- Bladder and bowel control problems

How to care for someone living with middle-stage dementia

How to keep someone healthy and active in the middle stages of dementia

It isn’t always obvious how best to entertain a loved one with Alzheimer’s or dementia. Activities like chores, gardening, and reminiscing about the past can help keep people busy — and be a mood booster, too.

- Social interaction is so important for people living with dementia. Old friendships could fade away as people may feel uncertain about ways to communicate with the person living with dementia or fearful of what the future holds. But a diagnosis could also strengthen old ties and lead to new connections. Caregivers should build it into the schedule whenever you’re able — in ways that give them some time for themselves, if they can.

- As much as possible, engage the subject of your care in activities they’re comfortable doing, within and outside the home. Here are eight expert-vetted suggestions for manageable activities that can benefit people living with dementia.

- Music can be therapeutic and good for engaging the brain. Neurologists and licensed music therapists can confirm that this is true for people with and without dementia. Here are a few expert-backed tips for incorporating music into dementia care at home.

- Plan easy-to-prepare and varied meals — for yourself and for your care subject. Allow them to choose what they’d like to eat whenever possible.

How to support everyday care needs through middle-stage dementia

- Create a routine for doing daily tasks like eating, bathing, and sleeping, and help them follow it strictly.

- Keep the person’s appointments, meetings, and tasks in a note or calendar.

- Create time every day for activities they enjoy.

- Choose comfortable outfits for them to wear

- Allow them to participate in personal tasks like bathing as much as possible.

- Serve them with foods they’re used to and in a familiar environment.

- Set up reminders to encourage them to do tasks like taking their medications.

How to manage middle-stage dementia’s behavior changes

While dementia leads to memory loss and makes it difficult to carry out everyday tasks, the disease also changes one’s personality. Among some of the expert advice we’ve gathered on managing dementia’s behavioral and personality changes:

- Listen and reassure a person with dementia when they air out their concerns.

- Respect their privacy and need for quiet time.

- Gently remind them when they show forgetfulness or confusion.

- Have regular and normal conversations with them. (Have you checked out our panel conversation on how to talk to someone with dementia?)

- Help them feel secure and comfortable in their environment by keeping it familiar with cherished photographs and objects.

- Allow them to live as independently as possible.

How to make the home safe and accessible for a person in mid-stage dementia

Speaking of living independently: Adapting to the physical, cognitive and behavioral changes associated with dementia is key to living well — and making a home environment safer and easier to navigate plays a central role. However, creating a safe, comfortable home environment for a person living with dementia isn’t just about shopping up the right homewares and creating the right design features: Experts say it also takes some planning ahead. For example:

- Simplify and organize — follow these expert tips for dementia-friendly design and decluttering.

- Vision problems grow more common with aging, and because dementia can affect parts of the brain that handle visual information, it often compounds age-related vision impairment. This can mean depth perception issues, a smaller field of vision, diminished tolerance of glare, and difficulty distinguishing one object from another. Consider lighting and contrast to help prevent falls.

- Make architectural and design modifications for safety, like ensuring stairs have at least one handrail, or putting grab bars in the bathrooms.

- Dig deeper into dementia-friendly home design and organization considerations in this LiveTalk with home design expert Grant Warner.

How to care for yourself — while caring for someone in dementia’s middle stage

A caregiver’s responsibility increases with each stage of dementia. Alzheimer’s and dementia caregiving experts remind caregivers to care for themselves as well, ask for help when they need it to avoid caregiver burnout — there are resources out there. For example, did you know it may even be possible to get paid for being a family caregiver?

Learn more about assembling a caregiving team here.

Learn more about avoiding burnout and seeking support with dementia caregiving here.