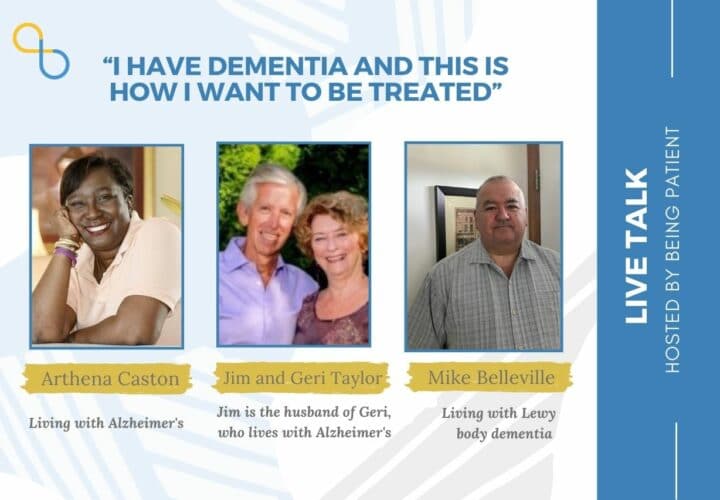

Perspectives from people living with dementia: Arthena Caston, Mike Belleville and Geri Taylor, who are living with dementia, and Taylor's husband Jim, talk about the stigma around the illness.

Dementia is a complex illness — one that is often misunderstood. The person’s age at the time of diagnosis, the severity of the symptoms and nature of its progression vary from one person to another, but dementia is often thought of as a condition that only affects older adults, one that strips people of their day-to-day abilities shortly after a diagnosis. Misconceptions of dementia, however, are stigmatizing for those living with the illness.

Being Patient spoke with Arthena Caston, Mike Belleville, Geri Taylor, who are living with dementia, and Taylor’s husband Jim, about the interactions they have encountered — both the good and the bad — and ways for people to become more attuned to the realities of those living with dementia.

- It is often assumed that people with dementia are, by default, in the late stages of the illness — wheelchair-bound or bed-bound, disorientated and unable to recognize loved ones.

- Old friendships could fade away as people may feel uncertain about ways to communicate with the person living with dementia or fearful of what the future holds. But a diagnosis could also strengthen old ties and lead to new connections.

- Interviewees urged clinicians to offer a more hopeful message to patients, helping them find resources, stay socially connected and participate in clinical trials.

Being Patient: In terms of the way people treat you, what has been the hardest since you’ve received a diagnosis?

Mike Belleville: As soon as you tell someone you have a dementia diagnosis, especially if it’s somebody you haven’t seen for a long time who may not know or even a stranger, their automatic assumption is that you’re in the latter of progression of the disease, that you’re not capable of doing things that you used to do before, that you’re not capable of learning new things. They talk slower to you. Some of them may talk louder to you. It’s just a laundry list of things that go on and on and on.

Geri Taylor: I had a soft landing … but Jim just reminded me of one of the interesting points. A couple of years ago I needed to go to the doctor to fix up something around my neck or whatever. He kept talking to Jim … It diminishes your own ability to work yourself.

Jim Taylor: Geri was audacious enough to question what he wanted to do. In the 1970s, Geri wrote the first article about second opinion. But I think he was trained overseas and didn’t like to be questioned.

For so many years, people have hidden the disease as long as possible because of the stigma. Therefore society viewed someone with Alzheimer’s as in the late stage because people would only come out when they couldn’t hide this information more.

Because the stigma has diminished and these three wonderful people on the screen here and you (LiveTalk host and Being Patient Founder Deborah Kan) are working very hard to diminish it continually, I think people have the courage now to come out earlier, but people dumb them down. One of Geri’s presentation a year or two ago was called ‘We’re Not Stupid.’

Arthena Caston: People that know me know that I’m very outspoken … The doctors tend to want to speak to my husband and that happened to me before I even got the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s.

I just calmly said, ‘But I’m sitting right here. I can hear. I don’t need you to talk to my husband. Talk to me about what you want to say.’ And the doctors’ like, ‘Yeah, but I don’t know if you understand.’

Being Patient: Do you get upset when people say you don’t seem like you have dementia. Is that offensive?

Mike Belleville: It used to be. I used to pull out the old Foghorn Leghorn. For folks who don’t know, it’s like, ‘Listen to me boy. Listen to me when I’m talking to you.’ But now I tell them, ‘Thank you.’ I’ll ask them if they have any questions or any concerns or what made them even say that to begin with.

It’s almost a double edged sword for us, especially because appearance wise, talking wise, we’re doing pretty well. But when people see us during our downtimes, it’s almost automatically assumed [it’s the disease]. I’ll just give an example. If I’m trying to do something on a computer or if I’m trying to do something like cooking and I’m getting frustrated, angry, it’s automatically assumed that it’s the disease: ‘Oh, Mike can’t do that anymore.’ It could just be I’m having an off day. It’s got nothing to do with the darn disease. It is what it is. I say a double edged sword because I understand that it’s tough for care partners and family and everybody else to see us going through struggles, but let us continue to try. Let us continue to attempt to do the things we want to do. Don’t just assume because we had a bad day, that means that part of our life is over.

Being Patient: Are friendships hard to maintain?

Geri Taylor: I’ve been very fortunate and I had a group of friends coming together, mostly for book groups – very lady thing. That was a very good thing for my coming out and that group has continued … When they’re going too fast, somebody will say, ‘Wait, Geri can’t get that.’ I kind of love that because it isn’t like having a disease that goes in a month. We’re around. We’re part of the community and we act that way, just slower. I was fortunate to have an embedded group of people and we have a few people in the family as well. That makes it easier to be with people.

Mike Belleville: In the beginning, a lot of people that I thought I was really close with, which was mostly my work relationships, just kind of faded away. I do have a couple of close friends that I am still very close with, thankfully. They haven’t disappeared. Something like that bothered me for a long time, but I’m actually closer with Geri and Jim and Arthena and people that I’ve met online through this journey of ours. I consider them family. I’m closer with the majority of these folks than I am with some of my own siblings.

Arthena Caston: My friendships are just like Mike’s: I started friendships with some people in a group that have early stage Alzheimer’s. Those are my best friends. It was nine of us in a group and we are like sisters and brothers. I have two or three friends that I was very close with. They’re still really close. We’ve been friends over 30 years. But the new friends that I’ve picked up, I’m closer to them than any other group and I love that because they know what I’m going through. They understand what I’m going through. They may call and say, ‘You having an off day?’

‘I’m having an off day today,’ and they understand what I’m saying whereas if you tell somebody else, they kind of think maybe it’s time that she’s moving down.

Understand me for who I am. I’m the same person. I am the very same person that you knew before. I might be a little slower with some things. I talk a little slow, take a little more time to understand, but I am the same person.

Being Patient: Arthena, how has your relationship with your husband changed?

Arthena Caston: Our relationship has gotten better because he is more of a person who will take the time to say, “Are you okay? How are you feeling today?” I wouldn’t trade him for nothing in the world. We even work together now. He gave me a little part time job at his store … He’s a keeper. He has really stepped up to the plate with this journey. I know it’s a journey for him. It’s a journey for both of us. It’s a journey for my whole family, as with all of us. He has always said that God put him on this earth to take care of me and that’s what he’s here for. If roles were reversed, I would do the same for him.

Being Patient: Having a wonderful companion makes a big difference, doesn’t it?

Mike Belleville: I would like to add a caveat to that though. I know some single individuals who are going through this journey alone who are doing extremely well. I honestly think the biggest reason is because we’re all staying socially engaged. We’re staying connected. We’re staying active. We’re doing things that are meaningful to us.

We’ve all sat on committees and councils and all these types of things and they’re not tokens. The people fortunately that we’re working with are taking it seriously. I truly think that means a lot.

Being Patient: How could doctors better approach and care for their patients with dementia?

Arthena Caston: When you get ready to tell me, or you find out that I have Alzheimer’s or dementia or whatever, stop telling me and everybody else to go home and get your house in order. Everybody that I have talked to says the same thing.

Don’t tell me that because the day that he told me, ‘I have given you five to eight years to live. Go home and get your house in order,’ even though I’m a very happy person, I came home and I was just done.

Jim Taylor: Maybe it’s different whether you hear the words from a neurologist or from a general practitioner (GP). A majority of people hear it from a GP. They are not experts in dementia and that’s just a small part of their general practice.

But probably from a neurologist, you would think you would get a more enlightened handling of informing you. But that’s I think not the case. Very often it’s diagnose and adios because there’s no medication they can give you now that slows or cures or prevents the disease, and that may change soon, and there are some that mitigate the symptoms.

When we were diagnosed, Geri took it very well. I did not take it well at all. She has had family experience and her health background, but I was depressed and really uncommunicative for a number of weeks. It would help so much if the referring physician could say, ‘Here are resources. Go to the Alzheimer’s Association. Go to your local support group. Here are online resources where you can go and learn about the disease, and consider being in a clinical trial.’

These are all such positive things and so easy and should even be the GP’s response. So many people don’t join clinical trials. Why? ‘My doctor didn’t recommend it. I’m not sure if it’s good for me.’ That just doesn’t make any sense. There’s a lot we can do, like Arthena said, to educate and help with that.

Mike Belleville: Stop the doom and gloom. Stop the tragedy narrative. We all know what the endgame here is. You don’t have to tell us. But instead, try giving us a little bit of hope instead of despair. No doctor knows how long a progression is going to take. So stop telling us to go home, like Arthena said, and get your affairs in order. One doctor looked at Cheryl and told her I’d be in the nursing home in three to five years. We did things based on that information because he was a doctor. Wrong information. Obviously.

[Doctors may say,] ‘This is not the best news I want to give you, but you can still live a meaningful, purposeful life. You can still contribute to society. There’s things you can still do and get engaged with. Find out whatever your creative outlet is and get connected with people.’

I truly believe the number one prescription doctors should be giving a person with a dementia diagnosis is social engagement. It’s not a pill. Don’t get me wrong, we’ll take our medication but people should be getting connected, socially engaged.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Contact Nicholas Chan at nicholas@beingpatient.com

Thank you Deborah Kan for the thoughtful interview. The interviewees provided information which we can use to understand and communicate with others who have this disease. I also appreciated the journalist, Nicholas Chan for the edited text version. Providing the video and text version helped me to retain the information.

Thank you, both my Mom who is 95 and my husband 84 have dementia. My Mom was put in a Foster Home, bur my husband is at home with me. Now I know more that my husband can do some housechores and activities. I just have to ask him for his help. He has very short term memory.

Gloria, thanks so much for being here and for sharing your story. Involving your husband in simple household tasks and activities is a great way to keep him engaged and give him a sense of purpose. We’re sending our best wishes to the two of you and to your mom.