Certain medications and health factors could increase your risk of side effects when taking LEQEMBI™ and other monoclonal antibody drugs for Alzheimer’s. Here's what patients need to know.

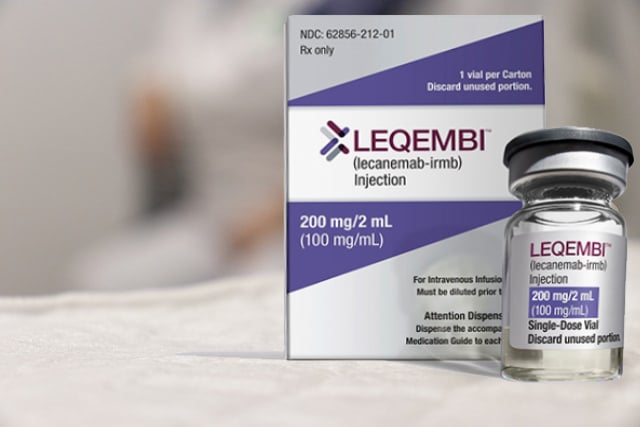

In January of 2023, the Food and Drug Administration approved the second anti-amyloid therapy for Alzheimer’s disease, Leqembi (generic name lecanemab). A new Alzheimer’s drug by drugmakers Eisai and Biogen, it earned this early approval via the FDA’s Fast Track, Priority Review and Breakthrough Therapy designations. Then, in July, Leqembi became the first Alzheimer’s drug of its kind to receive full, traditional approval from the FDA.

This is the drugmaker’s second monoclonal antibody. The first was Aduhelm (generic name lecanemab), which was given conditional FDA approval in summer of 2021 and is on the market but with limited availability. Clinical trials for Aduhelm are still underway.

(In February 2024, Biogen took Aduhelm off the market indefinitely.)

Also in summer of 2023, the CMS announced that, due to Leqembi‘s full traditional approval status, it does plan to extend Medicare coverage for Leqembi. The drugmakers had previously released a statement saying the price will average $26,500 per year per patient. (Aduhelm is not covered by Medicare.)

Monoclonal antibodies like Leqembi are designed to target the disease itself by targeting beta-amyloid protein plaques that build up in the brain during Alzheimer’s. Most previous drugs approved for Alzheimer’s are designed to treat Alzheimer’s symptoms like brain fog, confusion and memory problems, but they don’t impact the pathology of the disease itself.

Virtually all drugs carry some degree of risk. Leqembi is no different. Here is what you need to know about the risks that increase the chances of adverse events.

Leqembi side effects

The new Alzheimer’s drug label lists a few potential effects. Common but minor side effects via intravenous infusion, according to the Leqembi label, include: “Cough, diarrhea, headache, nausea, flu-like symptoms, vomiting, blood pressure (especially during first infusion).”

Then, there are side effects that are known to be linked to this class of Alzheimer’s drugs, monoclonal antibodies. Those include something called ARIA.

Amyloid Related Imaging Abnormalities (ARIA)

Looking closely at people on the drug within the first of 14 weeks. Risk of ARIA (symptomatic and asymptomatic) is higher for people with two copies of APOE4. If a patient experiences symptoms suggestive of ARIA, clinical evaluation should be performed, including MRI scanning if indicated. “Consider testing for ApoE ε4 status to inform the risk of developing ARIA when deciding to initiate treatment with LEQEMBI.” Later in the booklet, it says that you should tell parents there’s an APOE4 test available if patients want.

Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIAs) are small brain bleeds and swelling that occur as a side effect of anti-amyloid drugs. These reactions occurred most often in participants who carried two copies of the APOE4 gene, a genetic variant linked to Alzheimer’s risk.

In the aducanumab trials leading up to Aduhelm’s FDA approval for Alzheimer’s treatment in the summer of 2021, ARIA occurred in more than one third of patients receiving the high dose of the drug.

Comparatively, Leqembi appears safer: One in five people who received Leqembi experienced ARIA. Among these cases — only 3.5 percent were symptomatic.

Some factors that may increase a person’s likelihood of an adverse event while taking Leqembi

While the drug is very new, there is evidence that certain health factors may increase a person’s likelihood of an adverse event while taking a monoclonal antibody drug for Alzheimer’s, including Leqembi.

Infusion-related Reactions

Like its predecessor Aduhelm, Leqembi is administered by intravenous infusion. (Other injection methods are in trials.) The drug’s label warns that if a person is prone to or experiences infusion-related drug reactions, the drug may not be advised.

“The infusion rate may be reduced, or the infusion may be discontinued, and appropriate therapy administered as clinically indicated,” the label reads. “Consider pre-medication at subsequent dosing with antihistamines, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or corticosteroids for those reactions.”

APOE4, or the “Alzheimer’s Gene”

Leqembi’s drugmakers have highlighted that carrying two copies of the APOE4 gene does confer “an especially high risk of life-threatening brain hemorrhage.” Experts strongly recommend patients undergo genetic testing for the presence of this gene variant before deciding whether or not to take the drug. Presently, this testing is an out-of-pocket cost to patients.

According to Madhav Thambisetty, neurologist and senior clinical investigator at the National Institute of Aging, experts are watching the data for Leqembi closely to better understand specific risks for patients.

Thambisetty believes that if the drug does receive FDA approval, physicians must account for risk factors like APOE4 before prescribing the drug.

Other researchers and clinicals Being Patient interviewed took an even stronger stance, saying that the risks are too great to justify the drug’s use: Karl Herrup, an Alzheimer’s researcher at the University of Pittsburgh, expressed concern about the long-term impact of ARIA for patients taking monoclonal antibody drugs for Alzheimer’s. “I would say to a patient group that I recommend against it,” Herrup told Being Patient.

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy

Up to 80 percent of people with Alzheimer’s people with Alzheimer’s have a condition called cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). In CAA, amyloid plaques crowd the brain’s blood vessels, replacing the muscles that normally surround them. Leqembi and other anti-amyloid antibodies weaken the blood vessels by getting rid of these plaques. The blood vessels become weak and susceptible to hemorrhage.

People living with Alzheimer’s and CAA might have a higher risk of brain bleeds if they opt for a monoclonal antibody treatment like Leqembi.

A pre-existing history of vascular events in the brain

Leqembi’s label warns that people with the following factors take “extra caution” when taking Leqembi: “Four or more microhemmorhages, brain lesions, brain swelling, aneurysm, vascular problems, stroke.”

Blood thinners / anticoagulant medications

In the middle of Leqembi’s Phase 3 trials, the drugmakers issued a revised study consent form that included an updated warning for patients: Taking anticoagulants or blood-thinners along with Leqembi increased the risk of serious brain bleeds or death. They estimate this occurs anywhere between one in 100 to five in 100 people.

Patients who were already enrolled in the clinical trials were asked whether or not they wanted to continue, given this additional risk. Some common clot-busters are also given as the first-line of treatment for stroke; this means that doctors who see patients with stroke-like symptoms will need to consider previous anti-amyloid usage.

According to third-party experts who reviewed the Leqembi death cases, anticoagulant use may have contributed to worsening of ARIA in the first two reported deaths from the open label-extension trial.

While Eisai acknowledged and investigated these deaths, they said in a previous statement that they did not believe they were linked to Leqembi — despite warning of the link during the consent process in the trial.

“Both cases had significant comorbidities and risk factors including anticoagulation contributing to macrohemorrhage or death,” Eisai said in earlier statements. “Therefore, it is Eisai’s assessment that the deaths cannot be attributed to Leqembi.”

Matthew Schrag, a neurologist who reviewed the medical documents for the third death in the open-label extension trial and raised concerns over transparency about the risks of these treatments. “This appears to be a highly unusual cause of death and should not be dismissed as expected or common,” Schrag tweeted. “If Eisai and Biogen will not acknowledge that this case has an extremely high probability of being treatment related, how can you trust [the] remainder of their safety data for Leqembi?”

How to mitigate the risks of Alzheimer’s drugs like Leqembi

Unlike in previous Alzheimer’s trials, where only those among the healthiest 25 percent of people with Alzheimer’s disease might qualify, Leqembi trials welcomed participants with other medical comorbidities, such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, hyperlipidemia, and heart disease. This is riskier for trial participants, as drug interactions with these comorbidities aren’t well known. It also leads to a more accurate representation of risk in a general population, ideally producing data that could save lives later.

At this point, however, it isn’t clear whether any of these conditions increase the risk of developing complications during the course of Leqembi treatment. Instead, it will be up to patients and their clinicians to be vigilant for signs of side effects and stay one step ahead.

This has left many patients, advocates, and clinicians wondering how to best assess the risk and spot ARIA early. It is expected that this guidance on this will be provided to clinicians after approval.

“Whether routine APOE genotyping of eligible patients will be required by regulators if the drug is approved is an important question,” said Thambisetty. “Assessment of an individual patient’s risk versus benefit profile is a crucial part of clinical decision making and I hope that the prescribing label for the drug, if approved, will provide detailed guidance on this issue.”

According to Eric Smith, a neurologist at the University of Calgary, patients who receive the drug will need to be monitored through several annual MRI scans and education may be needed to ensure that doctors outside of specialized clinics recognize the signs of ARIA.

The lecanemab trial protocol outlined that safety MRIs should be conducted at nine and 13 weeks of treatment, then every three months for the first six months, and every six months afterward.

Lon Schneider, physician and professor of psychiatry at Keck School of Medicine tweeted that a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) may need to be implemented.

This means that the FDA could also require Eisai and Biogen to develop strategies, like increased monitoring or physician education, to ensure the safety of the patients taking this newly FDA-approved drug for Alzheimer’s.

UPDATE: 3 March 2024, 8:05 PM ET. In February 2024, Biogen took Aduhelm off the market, citing financial concerns. Although the drug did receive accelerated, conditional FDA approval for the treatment of early Alzheimer’s disease in 2021, it is no longer available to new patients. The company announced it would sunset trials in May 2024 and cease supplying the drug to current patients in November 2024.