Cinical trial investigators for aducanumab (Aduhelm) discuss the significance of the drug’s recent FDA approval, the controversy surrounding its efficacy, and the uncertainty ahead.

This talk is part of our LiveTalk series.

UPDATE: 3 March 2024, 8:40 P.M. ET. In February 2024, Biogen took Aduhelm off the market, citing financial concerns. Although the drug did receive accelerated, conditional FDA approval for the treatment of early Alzheimer’s disease in 2021, it is no longer available to new patients. The company announced it would sunset trials in May 2024 and cease supplying the drug to current patients in November 2024.

Despite much debate about aducanumab’s benefits for Alzheimer’s patients, the FDA has issued the landmark decision of approving the drug on Monday, making the drug, brand name Aduhelm, the first Alzheimer’s treatment to be green-lighted by the agency in nearly two decades.

Some experts say that the approval of aducanumab represents the first step into a new era of Alzheimer’s treatments, therapies that target the pathology of the disease such as beta-amyloid plaques. But others believe there is insufficient evidence to support its approval given the conflicting evidence from Phase 3 clinical trials, which were halted prematurely. Biogen, the drug maker that co-developed aducanumab with Eisai, is now required by the FDA to conduct a new clinical trial of the drug, and the federal agency noted that aducanumab could be removed from the market if the study fails to validate the benefits of the drug.

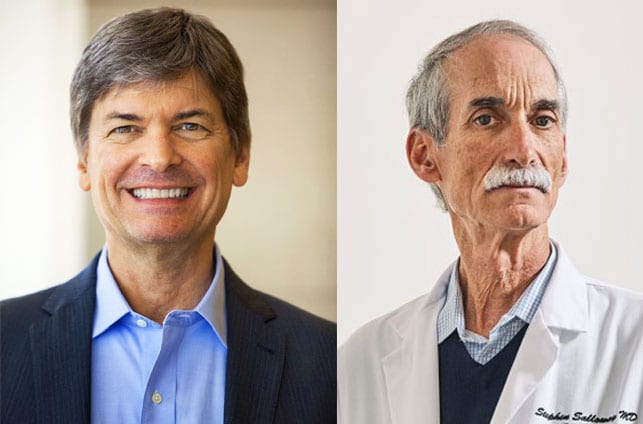

Being Patient spoke with Dr. Stephen Salloway, a principal investigator of the aducanumab clinical trial and the director of Butler Hospital’s Memory and Aging Program, and Dr. Lon Schneider, the director of the California Alzheimer’s Disease Center at USC who was a site investigator in one of its clinical trial, about the FDA’s approval of the drug and what it means for patients, families, researchers and clinicians in the Alzheimer’s community.

Being Patient: Can you sum the details of the aducanumab approval by the FDA?

Dr. Stephen Salloway: This was an accelerated approval pathway that the FDA used and they did impose a condition that an additional placebo, controlled trial would be conducted to try to replicate the positive results seen in one of the trials, and further action could be taken based on the results of that trial.

Dr. Lon Schneider: The basis of approval was on the antibody’s ability to decrease plaque and [the FDA believes] that the decrease in plaque would establish a reasonable potential that clinical benefit could be shown. This is a bit unusual to approve a drug on a biomarker — it has not been done in dementia or Alzheimer’s or most of neurology or psychiatry. It is done in cancer, where biomarkers that can predict, for instance, outcome to a greater or lesser extent, [are used]. For instance, the size of a tumor in some cancers and the reduction in the size of the tumor can predict survival.

Being Patient: How significant is the FDA’s decision?

Dr. Stephen Salloway: I think this is a turning point in Alzheimer’s research. I’m hoping this will open the door to a new treatment era for Alzheimer’s, where we have to do biomarker testing to confirm Alzheimer’s disease, and hopefully we have this treatment and others that will follow that we can build on that modify the underlying pathology and slow the course of the disease. Lon is right: There’s still much more work that needs to be done with this approach. There’s no time to waste. This is just the beginning, and this will pose challenges, but I think overall, this is clearly something very positive for Alzheimer’s patients and families and for the future.

One urgent need right now is to validate promising blood tests that can predict amyloid plaque and the build-up of tau tangles — another important protein in Alzheimer’s. Blood tests [are] looking really good. But there just aren’t going to be enough PET scans or it’s not going to be accessible or practical to do lots of spinal taps here in the United States. We need to really urgently move that forward.

The second issue is learning about your risk. I think it’s less of an issue once you already have cognitive impairment, because obviously something is wrong, causing you to have memory difficulty, and Alzheimer’s may be the reason. Finding out hopefully gives you new options for how to manage your life but also how to treat it. I think what’s going to be even a bigger issue in the future — and it’s already here — is finding out about your risk before there’s any memory loss. This is where the blood tests and PET scans and genetic tests and so many others would come in. That’s a very individual decision. Some people are very eager to know and be proactive. Some people are really frightened and don’t want to even consider it.

“I think this is a turning point in Alzheimer’s research. I’m hoping this will open the door to a new treatment era for Alzheimer’s.”

Being Patient: Dr. Schneider, what are your thoughts about the FDA’s approval?

Dr. Lon Schneider: This is a double-edged sword, and by approving the medication on the basis of a change in the biomarker, the FDA has essentially elevated that biomarker — the amyloid in general — to a premier place, to a major place, where just as Dr. Salloway described, we have these various tests to see if somebody’s amyloid is statistically higher, but older people in their 70s, for example, can be perfectly cognitively normal and have elevated amyloid. That then becomes a statistical risk that they are more likely to develop cognitive impairment than their twin who does not, but not that much more likely over the next several years.

So then what do we do? We have a drug that’s approved to decrease that biomarker — those plaques — and we have a good amount of uncertainty about ultimate benefits. That comes back to the uncertainty of the approval indication.

Dr. Stephen Salloway: I don’t really view it as a double-edged sword. But first of all, I want to give a big shout out to Lon. We’ve been warriors in the Alzheimer’s world for decades. This is one of many compounds that we tested and we participated [in many other trials] together. Even though we may disagree in our perspective, we’ve been united in fighting Alzheimer’s for many years.

I see it as an advance. I see that having this treatment — and I understand Lon’s points and they’re well-taken — will make these tests more readily available and hopefully covered. There will be spinal fluid testing. I’m hopeful amyloid PET scans will be covered as well. What was not available will now become available. I feel I’m a pretty good clinician. I’ve been at this for a long time, but some people I can’t tell if they have amyloid plaques: Some things look like Alzheimer’s but they aren’t. Having this test available is really going to help, especially for doctors with less experience.

I think we need to go the next step to develop the blood tests because these PET scans and the spinal taps just aren’t practical for a large number of people, and [they’re] too expensive. We got to do better. I think we’re on the verge of that, and this is sort of tangential to this approval, but I think this will accelerate that.

Being Patient: Dr. Schneider, do you think there’s enough data to bring aducanumab to the market [at which point it will be called Aduhelm] for people with Alzheimer’s?

Dr. Lon Schneider: The studies were set up to try to determine whether there would be cognitive improvement when we use the antibody. What was found is that the two studies were first stopped for futility, and then any evidence of cognitive improvement is not well supported. There’s no doubt this reduces plaque. Because there is not a demonstration of cognitive improvement, I think approving this for marketing was too soon.

“So then what do we do? We have a drug that’s approved to decrease that biomarker — those plaques — and we have a good amount of uncertainty about ultimate benefits. That comes back to the uncertainty of the approval indication.”

Dr. Stephen Salloway: This is a controversial data set. The trial was interrupted. We made a dose change right in the middle [of the study] for the ApoE4 carriers, which was two thirds of the trial population. A lot of them didn’t get to the top dose. Dose matters. [Biogen] did a futility analysis and they stopped the study early. The data set’s incomplete — [it goes] on and on. There are numerous issues with the data. Lon and I don’t disagree about that. But how do we interpret what the data in totality represents? I think we just have a difference of opinion about what the meaning is.

One of the studies in Phase 3 from the data that was available showed that there was a slowing of cognitive decline on global [and] cognitive measures. It was small but there was a significant difference. The other study did not show that, so that’s part of the controversy.

The earlier trial, which was smaller, showed some encouraging clinical results. One thing that I’m influenced by [is the fact that] I had 17 patients in that early trial that were on the drug for more than five years. This is data that Biogen presented to the FDA. Those that got the high dose for those five years had a slower cognitive decline. It wasn’t for every patient. We have to figure this out: Why does it work for somebody and not somebody else? I think we can test for tau and other things to try to start to solve that question to predict who’s likely to respond. The donanemab trial actually used a tau measure and only included people with a limited range of tau pathology in their amyloid antibody trial. Anyway, for 10 out of the 17 [patients in the early trial], there was a relative stability over more than three and a half years. You typically don’t see that in Alzheimer’s.

Want to learn more about clinical trials

for Alzheimer’s and dementia?

Check out the Lilly Trial Guide.

Being Patient: It’s important to emphasize that aducanumab has not been tested in patients in the later stages of Alzheimer’s, right?

Dr. Stephen Salloway: That’s really important … I think the approval [of aducanumab] is for Alzheimer’s disease … I’m concerned about this because the label is broad. I was hoping, if there was an approval, there’d be a more narrow label that mirrored the trial because the only evidence we have is from the trial.

Being Patient: What’s your team’s plan to administer aducanumab/Aduhelm?

Dr. Stephen Salloway: We’re planning to offer this drug, and we’re going to follow the clinical trial guidelines, and we’re going to make our own label … there’s really no evidence that it works for later stage disease and it probably doesn’t work for later stage disease because based on the biology of what we know about Alzheimer’s, the amyloid process pretty much peaks during the earlier stage.

Being Patient: So we don’t know whether aducanumab may benefit people in the later stages of Alzheimer’s.

Dr. Stephen Salloway: We have no data, and what we have is from other drugs that didn’t work. Also, I don’t know if the FDA gave guidance about amyloid testing, but I think we definitely need amyloid testing to determine eligibility for this treatment. In my opinion, it’s for those that are early Alzheimer’s [and] building up amyloid.

Being Patient: Do you have other concerns?

Dr. Stephen Salloway: I’m also concerned that … the safety guidance in the label doesn’t mirror the trial. I’m very experienced in monitoring for fluid shifts and we did it a certain way in the trial with a lot of backup [from] world experts … In the forums that I have, I’m going to encourage people to follow the evidence that we have, especially for safety, and we want good clinical practice. I can’t see how to do that by making it more liberal in a much broader population with much less expertise.

Dr. Lon Schneider: I hate to predict the future because I’m really not good at it, but I think that what we’ll also see is that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services will issue some considerable guidance about safety. They’ll essentially be saying, “We will reimburse to this amount in these particular patients who fulfill these criteria, and we’ll also reimburse for the appropriate safety tests if it’s followed in a certain way.” This is what we kind of depend on and we can’t depend on the FDA to give us all this detail when they approve the drug.

Being Patient: Dr. Schneider, do you have any additional thoughts about the uncertainties of aducanumab’s approval?

Dr. Lon Schneider: We don’t know the actual availability, the actual costs, the accessibility, whether people who are economically disadvantaged will have access to this.

Testing this in people who have more severe dementia, or for that matter, much more mild symptoms, would require formal studies. I wouldn’t want to wing it in the clinic.

Being Patient: Since aducanumab was tested in patients with early-stage Alzheimer’s, can you give us a better idea of the symptoms typically seen in this stage?

Dr. Lon Schneider: Earlier stages [of] Alzheimer’s disease pathology is having memory impairment that we can observe, that we can measure. It could be a slight degree but it’s clearly memory impairment that is not associated also with impairments of activities of daily living and function of driving, doing finances, doing checkbooks, shopping. That’s what we call mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Contact Nicholas Chan at nicholas@beingpatient.com