Here's the difference between treating Alzheimer’s symptoms and actually changing the course of the disease itself.

Despite decades of study, the underlying cause of Alzheimer’s continues to evade scientists. Because it’s such a mystery, there are only six drugs approved for treating this very prevalent disease. Most of them are just “band-aid” solutions — they’re deigned to improve people’s quality of life by treating Alzheimer’s symptoms, while the disease inevitably progresses.

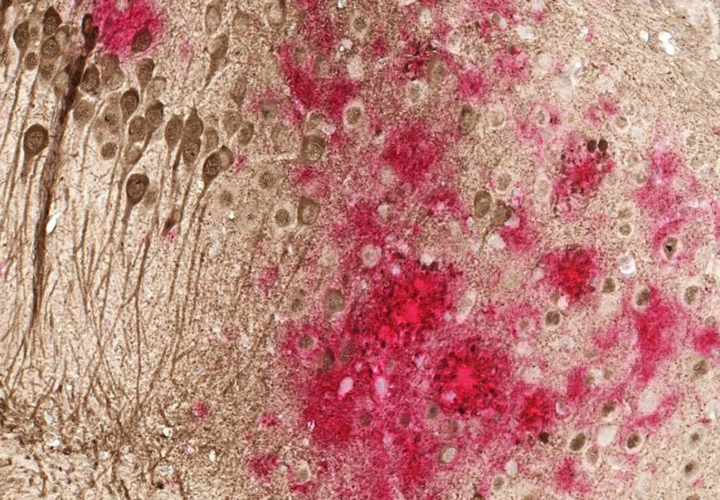

Until recently, because scientists don’t know the exact cause in order to target it, there haven’t been drugs designed to actually halt disease progression. But, honing in on the unproven but widely supported “amyloid hypothesis” — the idea that toxic beta-amyloid proteins clump in the brain and ultimately cause Alzheimer’s — scientists have designed a series of new drugs called anti-amyloids that are more than just a band-aid: They’re designed to target Alzheimer’s underlying pathology, stopping the disease from continuing to colonize the brain, instead of just treating its symptoms.

In the past two years, the FDA approved two of these landmark new anti-amyloid drugs: monoclonal antibody drugs called Aduhelm (aducanumab) and Leqembi (lecandemab). While the efficacy of Aduhelm is controversial, clinical trials of Leqembi were the first to show that reducing the levels of these plaques led to at least small improvements in cognition.

(In February 2024, Biogen took Aduhelm off the market indefinitely.)

So, what is the difference between treating Alzheimer’s symptoms and fundamentally treating the disease itself? And is this approach useful?

Treating Alzheimer’s Symptoms

The symptoms of Alzheimer’s often appear 10 or more years after the disease itself starts. By then, cell death in the brain has led to the collection of symptoms we recognize as Alzheimer’s: cognitive impairment, confusion, memory problems, trouble sleeping, and even changes in mood or personality.

Catching these symptoms at an earlier stage — in the first signs of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) — can give people with an Alzheimer’s diagnosis more time to make lifestyle changess that might mitigate symptoms and improve their quality of life.

In the meantime, there are a number of drugs out there designed to treat Alzheimer’s disease’s cognitive symptoms. For people with MCI or with early-stage Alzheimer’s, these symptomatic treatments can really improve day-to-day life.

However, behind the scenes, the disease will continue to progress. Brain cells continue to die off. And gradually, these treatments become less effective.

The mysterious extra benefit of galantamine

While symptomatic treatments aren’t intended to target Alzheimer’s root causes, some have shown the ability to go beyond their initial “band-aid” intentions, and actually potentially slow the disease’s progression.

Razadyne (generic name galantamine) was approved by the FDA in 2000 to treat Alzheimer’s disease’s cognitive symptoms, but it also appears to help remove amyloid plaque from the brain — just like the new wave of disease-modifying anti-amyloids that are currently in development.

A recent study published in the journal Neurology found that, compared to other symptomatic treatments, Galantamine may also reduce the risk of progressing to severe dementia.

Meanwhile, a Razadyne unexpectedly showed the ability to remove amyloid from the brain, but that was a happy coincidence, as it was designed as a “band-aid” treatment. New Alzheimer’s monoclonal antibodies on the other hand are specifically made to clear the beta-amyloid plaques. But the jury is still out on whether these drugs will make a meaningful difference for patients in the long run.

The age of the anti-amyloids?

There are more anti-amyloid drugs, designed to work similarly to Leqembi and Aduhelm, in the drug trials pipeline now. Time will tell if these drugs can turn the tide against Alzheimer’s, slowing the disease or halting its progression altogether.

The problem with anti-amyloid drugs is that are only designed to work for people in the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s. However, scientists are also working to design Alzheimer’s disease modifiers that can help people in the middle and later stages of the disease, too. Some of these later-stage Alzheimer’s drugs are already in trials.

UPDATE: 3 March 2024, 8:07 P.M. ET. In February 2024, Biogen took Aduhelm off the market, citing financial concerns. Although the drug did receive accelerated, conditional FDA approval for the treatment of early Alzheimer’s disease in 2021, it is no longer available to new patients. The company announced it would sunset trials in May 2024 and cease supplying the drug to current patients in November 2024.