My son was born one week before my father died and that near instant transition from caregiver to parent has defined the last sixteen years of my life. The day I travelled home for the memorial with a week-old baby was hectic, frightening and terribly sad. It was the first time I was reminded by a flight attendant to put my oxygen mask on before I attended to the needs of my child.

Whether you are a parent or a caregiver, this advice is crucial. Put your mask on first.

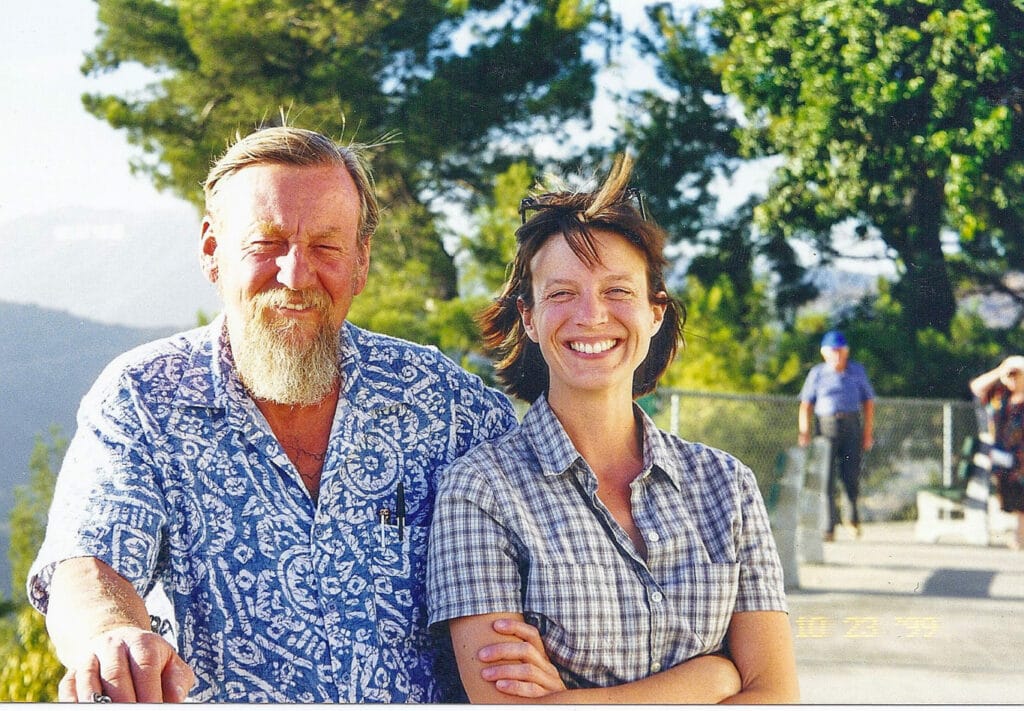

Of course, it’s an easier thing to say than to do. I know firsthand the difficult balance of caring for yourself and an ailing parent. My father was 57 years old when he was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. I was a few month’s shy of thirty. The doctors gave him five years to live and my mind went immediately to all the things I hadn’t done when I considered moving to be closer to home. I hadn’t been published, I hadn’t gotten married, I had no children, I had no direction. I’d been living in Los Angeles, working as an assistant in television production, but I had no savings account and no long-term employment goals. I said goodbye to my new boyfriend and dropped everything else (which is to say, nothing, but it felt like an upheaval of my life) and moved back to the mountains of Albuquerque, New Mexico.

According to the the Pew Research Center, 47 percent of adults in their 40s and 50s have a parent aged 65 or older and are either raising a young child or financially supporting a grown child.

Twenty years later, I realize how lucky I was to have the freedom to make this choice. Now I’ve got two kids, aged fourteen and sixteen. My husband works a demanding job and I write from home. I’m also the chief lunch-maker-homework-helper-driver-activity-planner-shoulder-to-cry-on-first-responder. As much as I would want to drop everything to care for my father, it would be hard to do. Long-distance caregiving would be another ball added to my daily juggling act.

According to the the Pew Research Center, 47 percent of adults in their 40s and 50s have a parent aged 65 or older and are either raising a young child or financially supporting a grown child. One in seven middle-aged adults are providing financial support to both an aging parent and a child. One fourth of those caring for parents with Alzheimer’s are members of this so-called “sandwich generation” and that number is growing.

I know it’s likely I’ll find myself in the role of caretaker again. I’ve got a set of in-laws, my mother and my stepmother. Added together, they’ve got over 300 years between them. They are all blessedly healthy in mind and body, but I think about how my life might change if one (or more) of them needed care. I think about what I would need to do to make sure I could balance my life as a parent, wife, writer, and daughter.

Remember that even as Dad began to lose his memories and words, it was still possible to connect over a meal.

In an effort to be gentle with my future self, I’ve come up with some helpful hints based upon my past experience. This is the letter I would give my past self—what I wish I had known from the very first phone call confirming a diagnosis.

- Ask for help. Your friends and family will undoubtedly say something like this: “If you need anything … ” They will trail off because although they want to help, they don’t actually know what you need. Tell them. Say, “That would be great. Could you to run to the market?” Then, hand them a list. Other things you might want to request: help with yard work, errand running and household fixes. You might ask this kind person to come over and hang out with your kids and/or your parent while you take a nap.

- Take as many naps as you can.

- As you become more focused on the health of your ailing parent, do not lose sight of your own health. Feed yourself good things. As I recall from my last round with Alzheimer’s, a diet of bourbon and potato chips is not going to sustain you, as comforting as it might seem in the moment. Instead, make a big pot of soup, fill your fridge with cut-up veggies and protein-rich snacks such as boiled eggs or hummus and pita. Remember that even as Dad began to lose his memories and words, it was still possible to connect over a meal. Come to think of it, the kids are old enough to cook without burning the kitchen to the ground. Provide them with recipes and ingredients. You’ll give them a sense of accomplishment and hone their life skills in one fell swoop.

- Hang out with people who “get you.” Chances are pretty good that other people in your community are going through a similar situation. If you can swing it, get out of the house to attend a support group. If that proves difficult, there are Facebook groups, blogs and websites for caregivers of all stripes and that means that there are like-minded souls ready to lend an ear at any time. Whether you need advice or just a little company, finding a support group online or in person can be a great source of sanity and comfort.

- Don’t forget that your kids need some alone time with you. Taking care of an aging parent can be all encompassing. A break with the kids might be just what you need. Watch bad TV, eat too much sugar, go for a bike ride or play video games. Get in touch with your kids and with your own inner child. Shooting down alien invaders or riding a roller coaster are great stress busters.

- Do you remember that day (OK, days) when the kids were little and your husband compared himself to a “screwdriver?” He was pretty bummed out that these new tiny humans zapped all your time and energy. He felt useful, but he didn’t feel loved. Your spouse deserves to feel loved. You deserve a healthy marriage. Walk around the block together, make a dinner date, write a love note or just say, “thank you for taking out the trash.” Sometimes it’s the smallest gesture that matters.

- If you are a long-distance caregiver, learn to trust those on the front lines. If you’ve hired help, assume that you’ve made a good choice. If other members of your family are doing the caregiving, try not to be a back seat driver. You will probably feel guilty. There will be some days when you won’t be able to stop thinking about your ailing parent and some days when you won’t think of them at all. Both scenarios are okay. When you visit, let yourself be fully present and do the same when you return home. Your brain and heart are going to ache with the effort of being two places at once. They will feel stretched to the limit, but trust that they will not break.

- You might shout at your kids, your parent or your husband. You will probably cry. You might slam a door or say something you regret. It happens. Try to make amends as best you can. Try to err on the side of love.

- Cut yourself some slack. You may recall that when Dad was sick, “It’s all we can do” became the family mantra. “All you can do” is not about doing everything, but about doing just what you are capable of in that moment. This phrase is one of reassurance and forgiveness. Realizing our limits was a way of being kind to ourselves and each other.

After school today, my kids will continue to tutor their grandparents in all things iPhone, my stepmother is preparing for a five-day hike and my mother is planning a bird watching road trip. Even though we are all happy and healthy and independent, once you’ve seen the devastation Alzheimer’s can swiftly deliver, you can’t help but plan for the future. I am grateful for the time we have. I’ll put my list away for now and savor this day.

Tanya Ward Goodman is the author of the award-winning memoir “Leaving Tinkertown,” which chronicles her experiences with the near-simultaneous diagnosis of her father with early-onset Alzheimer’s and her grandmother with Alzheimer’s. Her essays and articles have appeared in numerous publications, including the Los Angeles Times, Huffington Post, The Orange County Register, Luxe Magazine, Coast Magazine, and Panorama: The Journal of Intelligent Travel. You can find her on Instagram @twgoodman and on Twitter @campfiresally.

Spot on advice, Tanya. Caregivers need to take care of themselves, too, because if they break down, then they won’t be able to take care of the ones they love. We walked this road with my mother and her dementia.

Dear Tanya,

Thank you for this insightful article. Have you written anything else about the sandwich generation and coping with dementia from a family perspective? I’m starting a support group in my community for this demographic and including kids/teens. There doesn’t seem to be much communication about how dementia affects the whole family — focus is more on the primary caregiver and the person suffering from the disease.

Thanks!

Thank you for this! ❤️