Could an ultrasound unlock the secret to curing Alzheimer’s? Results from a recent study show that using the sound waves emitted by an ultrasound could be a game-changer for Alzheimer’s patients. Nir Lipsman, M.D., Ph.D., a neurosurgeon at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, and his research team shared the results from the first clinical trial that used ultrasound technology to open the blood-brain barrier in Alzheimer’s patients at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC) last month. The preliminary data from the trial, funded by the Focused Ultrasound Foundation, showed that using ultrasound technology to deliver Alzheimer’s-destroying drugs could be a real possibility in the future. But is it safe? And how does it work?

First, a little background: While the blood-brain barrier is meant to protect us by blocking toxins from getting into our brain, it can also prevent valuable substances from entering the brain, including potential Alzheimer’s drugs that could help eliminate beta-amyloid, the toxic protein that builds up in Alzheimer’s patients’ brains. In a non-invasive procedure that requires participants to wear a helmet and enter an MRI scanner for several hours, researchers sent high-frequency sound waves through five participants’ skulls to open the blood-brain barrier and target a specific area of the brain. Lipsman said that accessing the blood-brain barrier will allow researchers to deliver drugs into the brain more effectively. According to Lipsman, the act of opening the blood-brain barrier alone may prompt the body to start clearing beta-amyloid, so researchers are also studying how they can use this procedure by itself.

Although Lipsman said it will take years for this procedure to go through additional trials and receive FDA approval, he is hopeful that if focused ultrasound is approved as a treatment method, researchers can do additional trials that examine how this procedure may be able to treat various neurodegenerative diseases. Being Patient spoke to Lipsman at the AAIC about his findings, what it means to open the blood-brain barrier, whether there are any dangers involved with this procedure and how this technology could benefit Alzheimer’s patients.

Being Patient: You just announced that your research team used ultrasound technology in human patients with Alzheimer’s disease for the first time. Can you tell us about your research findings?

Dr. Lipsman: The tool we used was focused ultrasound. You can use low-frequency ultrasound to open the blood-brain barrier. The blood-brain barrier is a physical barrier that’s comprised of a layer of cells that [protect the brain]. We have this barrier for a reason: It prevents large compounds and toxins from getting into the brain and harming it. At the same time, it can also prevent a lot of potentially useful things from accessing the brain as well. The pursuit of a reversible and safe way to open the barrier has been sought after for many, many years because there may be effective treatments for various conditions, but you just can’t get them into the brain in a sufficient concentration. We showed in five patients with Alzheimer’s disease how to safely and reversibly open the barrier in a very focused way. That’s a necessary first step to using this technology to treat the disease.

Being Patient: Do your findings suggest that if you can open the blood-brain barrier, you can fight the plaques and tangles that are present in Alzheimer’s patients’ brains?

Dr. Lipsman: Yes. We’re looking at ultrasound in two ways: The first way is to look at it as a delivery strategy that essentially pokes a hole in the blood-brain barrier, temporarily, so that whatever is traveling in the blood stream—whether it’s an antibody or some drug that you want to get into the brain—can be delivered more efficiently. That’s using ultrasound as a delivery strategy. The second way is also potentially exciting, since it was shown in animal models that you may not even need to deliver a drug; just opening the blood-brain barrier alone may give the cells making up the body’s immune system access to those amyloid plaques and may activate cells in the brain that could help clear amyloid by itself.

Being Patient: What does opening up the blood-brain barrier entail? Does the process resemble a surgery using sound waves? How invasive is the procedure?

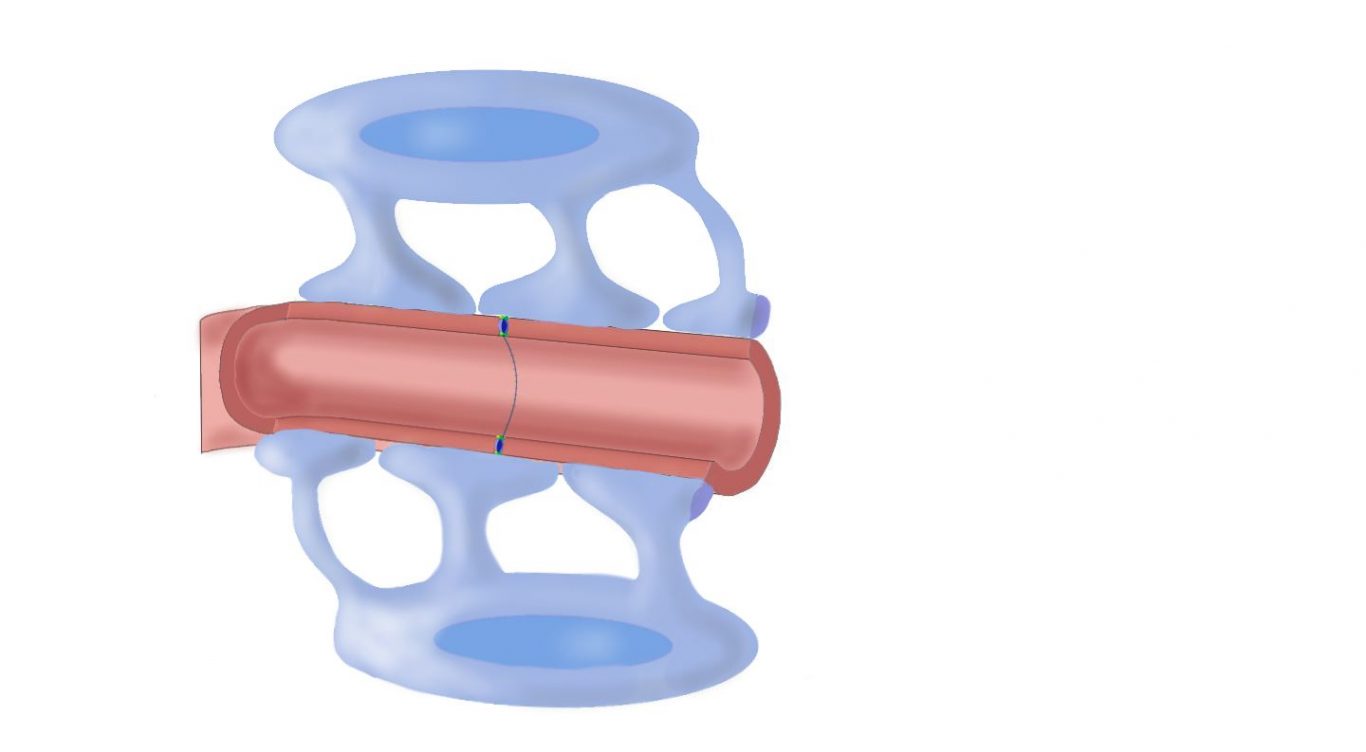

Dr. Lipsman: It’s essentially non-invasive. The procedure involves patients coming into the hospital. A frame is attached directly to their head with two pins in the front and two pins in the back. Then their head is placed inside a helmet. The lining of the helmet contains over 1,000 individual ultrasound transducer elements, or 1,000 sources of ultrasound. With their head in the helmet, they go into an MRI scanner. Then, we use high-resolution imaging to look at their brain and select which region of the brain to open the blood-brain barrier. But it’s not enough to just apply ultrasound. We need to inject patients with a special contrast agent that contains microbubbles. These microbubbles are small and contain gas. They circulate throughout the body, then get to the brain. When these microbubbles are exposed to ultrasound, they vibrate, increasing and decreasing rapidly in size. That vibration pulls apart the cells making up the blood-brain barrier, and it does so temporarily for about six hours. So there’s a six-hour window of opportunity to deliver whatever’s in the bloodstream into the brain.

Being Patient: What are the dangers involved with opening the blood-brain barrier? Can dangerous things like microbes get into it?

Dr. Lipsman: This question is essential to all of the work that we do. Safety is a primary issue and that’s why we did this Phase 1 trial. We know, for example, in the animal world, whether it’s in Parkinson’s animals, Alzheimer’s animals or even healthy animals, that when you open the blood-brain barrier with focused ultrasound, it looks like it’s safe. It looks like we don’t cause any bleeding, swelling or the introduction of anything bad into the brain. A lot of that has to do with the fact that it’s a temporary opening for only a few hours. In the human research, we’ve now shown that it also appears to be safe. We don’t see any bleeding or swelling in the brain—even microscopic bleeds that we can detect on an MRI scan. Patients themselves appear to do well too. We haven’t seen any evidence of inflammation, infection or anything negative when we’ve followed them after the trial.

Being Patient: What is your biggest concern with using this procedure going forward?

Dr. Lipsman: We want more safety data. We want a broader range of patients. The more people you treat, the more varied those people will be, so we want to make sure that this is safe in other age groups: in older people, in people with vascular risk factors and people who have two copies of ApoE4, [the gene associated with a higher risk of Alzheimer’s]. We have compelling safety data. We’ve done our first human trial, but now we want to look at more patients. This way, we can start doing what are called sub-groups. We can look at whether some patients respond better to the treatment or represent an increased risk. We need to better characterize the technical aspects of the procedure, the safety aspects and whether it’s actually achieving what we want to achieve.

Being Patient: There were only six people in your study. That doesn’t sound like a lot of people to test this procedure on. Why did you only focus on six participants?

Dr. Lipsman: Being a small study is one of the limitations, but treating only five or six patients is typical of Phase 1 trials for medical devices. The medical device world is distinct from the drug world. In the device world, a Phase 1 study demonstrating that something is safe is enough to continue to a larger study. It’s OK that the numbers are smaller.

Being Patient: Were any side effects observed among participants?

Dr. Lipsman: We did not see any serious clinical or other adverse events. We define that as anything serious—anything you could be hospitalized for. In addition to not seeing any bleeding or swelling, patients didn’t have any physical symptoms whatsoever from the procedure. It didn’t impact any of their brain function that we measured. Some minor side effects included discomfort with putting the frame around their head or being in an MRI scanner for about two and a half hours. That can be tiresome for many patients. However, those are temporary and what we call minor adverse events. All of these patients were discharged on the first day after the procedure and have expressed interest in participating in the next phase of the study. That’s an indirect measure of how well-tolerated it was.

Being Patient: How long did you monitor patients for after the procedure took place? Will you continue to monitor them, looking for long-term side effects?

Dr. Lipsman: We followed patients for two months after their procedure. We treated every patient in our study twice. The first time, they came in with the procedure that I described. We targeted a small region of their brain where the blood-brain barrier was opened. Then they came back a month later to have a slightly larger region of the blood-brain barrier opened. That was to demonstrate that the procedure is safe and that it can be done repeatedly and reversibly in larger volumes. We followed patients for a couple of months after that on the assumption that most serious adverse events occur shortly after you treat patients and operate on them. We remain in close touch with all of our patients and we know that they’re doing well from the physical perspective.

Being Patient: How many people will be in your follow-up study? Will you do the same study or take the next study further?

Dr. Lipsman: The larger study will aim to recruit 30 patients and we’ll treat patients multiple times. We’ll also treat multiple regions of the brain that we know has amyloid and tau in it. We’re going to measure a whole bunch of things in these patients—both through imaging, their blood, spinal fluid and clinical outcomes. We’ll look at all of these factors to better characterize the response to the treatment.

Being Patient: Where will the study take place?

Dr. Lipsman: Our study will be a Canadian study. It will recruit patients across Canada, but there is a study starting in West Virginia in the U.S. It was just FDA approved a couple of weeks ago. The person who will help lead that study is neurosurgeon Ali Rezai. This study is similar to what we’re doing in Canada to try and treat Alzheimer’s.

Being Patient: Let’s talk about the two types of treatment: one involves opening the blood-brain barrier and sending sound waves in there, while the other includes sending in medications that could be effective in combating plaques and tangles. What is the difference between these two techniques? What method do you plan to test first?

Dr. Lipsman: We’re going to start with the focused ultrasound alone trial, because you may not need a drug. The act of opening the blood-brain barrier alone in regions of the brain where you know there’s amyloid and tau may be enough to lower those. We need to see if that’s true. In conjunction with that, if we know that it’s safe, we need to do some studies that potentially pair ultrasound and the barrier opening with a drug. We need to make some modifications. For example, if you’re exposing the brain to increased concentration of a drug, you need to make some adjustments to the dose of that drug. There are many more questions that need to be answered about the drug, including which drug or compound to use, in what dose, where to apply it and in whom. The first question should be whether there’s any therapeutic benefit to just using ultrasound alone.

Being Patient: Could this technology be tested on younger people with a strong family history of Alzheimer’s, eventually leading to prevention at the earliest stage?

Dr. Lipsman: Yes. Our hope is to make this as broadly applicable as possible, but any time you have a new device or tool, the emphasis is always going to be on safety and making sure that what we’re doing isn’t causing any harm. Oftentimes, people who have a younger-onset illness have rare or genetic forms of the illness that could impart some additional risk. For example, in our next phase of the study, we exclude people who have two copies of ApoE4, which is a genetic type of Alzheimer’s; patients have excessive amounts of amyloid that builds up at younger ages. Theoretically, there may be an increased risk of causing a brain bleed in these individuals and we don’t want to do that. The more data we accumulate on safety and efficacy, the more confidence we’ll have about loosening restrictions at both age ranges: the low and high range.

Being Patient: Beta-amyloid is one of the markers of Alzheimer’s disease, but research suggests that we need a certain amount of beta-amyloid in the brain and our bodies. Is there any risk of eliminating too much beta-amyloid if you find that this is an effective way to reduce plaques in the brain?

Dr. Lipsman: Not really. It’s a waste product that is constantly made and cleared. We see the brain scans of the people we treat and their brains are caked with amyloid, so we know that it’s potentially having a profound effect on their brain. The most promising results from drug trials have shown that when antibodies are effective at the highest doses that are used, they clear amyloid to the point where it converts somebody from amyloid positive to amyloid negative. So removing amyloid or preventing its occurrence in the first place is a major goal of the field.

Being Patient: What stage of Alzheimer’s disease were the participants you treated? What stages will participants in future studies be in?

Dr. Lipsman: We enrolled patients in the mild to moderate range and to make that concrete, these are patients with Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores of 18 or above. We did not recruit people who scored less than 18 on that test. As a safety strategy, we didn’t want to recruit people who were too far along in the illness. The goal ultimately, and I think I can speak for many people in the field, is to try to intervene as early as possible in the illness. We know amyloid, for example, develops decades before people become symptomatic, so if there’s a strategy to intervene at earlier stages in a safe way, then that’s an important goal. All of the amyloid clearing trials are premised on the amyloid cascade hypothesis, which itself is open to debate in the Alzheimer’s community, but has dominated the therapeutic field in Alzheimer’s for decades. That’s the idea that you get amyloid, and the deposition of amyloid triggers a cascade of biochemical events, leading to the deposition of tau—another abnormal protein—inside neurons and that leads to neurodegeneration and brain dysfunction.

Being Patient: Would this procedure work with other types of dementia?

Dr. Lipsman: Possibly. With the second track of research, which involves using ultrasound as a delivery strategy, it’s up to the biomedical field to determine what should be delivered into the brain. For example, in Parkinson’s disease, we may want to deliver growth factors or something that targets alpha-synuclein, an abnormal protein deposit in Parkinson’s. Or maybe we’ll want to deliver stem cells in some instances that are appropriate.

In Alzheimer’s patients, is the procedure aimed at the hippocampus, the brain’s memory center?

Dr. Lipsman: In the trial that we did, it wasn’t. We targeted a region in the right frontal lobe known as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. This is a region of the brain where we thought it was safe to open the blood-brain barrier, in the event a bleed or swelling happened. Of course, every brain region is important, but some are more important than others, so we wanted to stay far away from critical motor structures or speech centers, vision centers, basic vegetative centers and things like that, just in case. Now that we have safety data, for the next phase, and for future trials, we would target what we call eloquent regions of the brain, so cognition, memory centers, such as the hippocampus, and other parts of the brain responsible for vital function.

Being Patient: What’s the timeline for your research? How long do you think it will be until you find an answer about how successful this technology will be? Will you have to go through the long process of getting FDA approval?

Dr. Lipsman: It’s a really good question and sometimes it can seem like it’s taking forever. But we need to remember that those regulations are in place for a reason and ultimately, they’re there to protect patients, researchers and institutions. The answer is yes, we need to go through a very rigorous regulatory and scientific process to show that it’s safe and effective. The medical device world is no different from the drug world. We have phases of trials: Phase 1 is a safety study, Phase 2 trials are additional safety studies that also help us gather important efficacy data, or measures built in to show that it’s doing what it’s supposed to be doing. Then there’s a Phase 3 trial where ideally, you compare a treatment or device to either the gold standard or to a placebo arm to definitively establish that you’re getting the therapeutic effect that you want to get. That timeline varies, but it will take years before we can really see if this has legs as a potential strategy for Alzheimer’s. Yet the power of ultrasound technology is that it is neutral to what you want to deliver. So if it’s approved as a delivery strategy, then you can do multiple trials with multiple therapies to see which ones may be effective. We’re in uncharted territory in terms of focused ultrasound and what its role could be in neurodegenerative illnesses, and in Alzheimer’s specifically.

Being Patient: What medications would you use in the process that involves inserting medications into the brain? Are there existing medications, or do they still need to be developed?

Dr. Lipsman: There are many existing ones and we heard some exciting results earlier at the AAIC about what are called monoclonal antibodies. These are antibodies that target amyloid. There are medications out there: IV drug infusions in the form of antibodies that are done monthly or twice monthly, where the goal is to deliver antibodies to target amyloid, to break it down and help clear it. The problem with antibodies is that they are several thousand times larger than the typical substance that can cross the blood-brain barrier. We’re only able to get 1 or 2 percent of those antibodies into the brain. If one can enhance that fraction even more, then maybe we can do better. Maybe we can clear more amyloid, try antibodies against tau or deliver growth factors to support neurons that aren’t quite so far gone to nurture them back to health. It’s both existing drugs and also ones that have yet to be developed.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.