USC quantitative neuroscientist Dr. Andrei Irimia joins Being Patient Live Talks to discuss his research on brain aging and AI technology.

Especially as the recent launch of ChatGPT — an alarmingly smart, artificial intelligence-powered text generator that can write a school term paper about as well as a high school student — makes news headlines around the world, people across most every job and industry are investigating how the growth of AI can change how we work and live. Of course, scientists have already been studying this potential for decades, and when it comes to brain health and neurology, some — like Dr. Andrei Irimia at University of Southern California — are testing this technology could change how we think about our brains and approach Alzheimer’s diagnosis.

A quantitative neuroscientist, gerontologist, and biomedical engineer, Irimia uses computational biology approaches and multimodal imaging to study brain aging in health and disease. In his latest research, he and fellow USC researchers developed an AI model — a way to measure data powered by artificial intelligence — to accurately capture cognitive decline.

There are a few ways AI is being applied to diagnose and measure cognitive decline already: for example, AI-powered cognitive tests a person takes on a digital tablet such as an iPad. Irimia’s team is trying a different approach: They are looking at the rate and degree of cognitive decline by measuring how fast the brain is aging.

In a conversation with Being Patient EIC Deborah Kan, Irimia shares insights into the latest findings from this research, including key differences he is seeing between the rates of “brain age” in males versus females. He’ll also discuss how different areas of the brain age — and how this innovative AI model could help us learn more about a wide range of brain health concerns, including Alzheimer’s.

Watch the full conversation in the YouTube video below, or read a transcript from the discussion here:

Being Patient: I’ve heard that we only understand about 1 percent of how the brain works. Is that true? Do we really know so little about the brain?

Andrei Irimia: Well, it’s interesting because there’s been such tremendous progress in the past few decades. In some ways, we know quite a lot. We know a lot about the organization of the brain. We know about the areas of the brain that are affected by Alzheimer’s disease and by aging. We also know a lot about the processes in the brain that give rise to mental health diseases or other neurodegenerative diseases. But you’re right. There is a lot that remains to be explored and discovered, and we’re happy to be at that frontier.

Being Patient: How much can imaging in MRIs and PET scans tell us about our brains? Especially in terms of brain age?

Irimia: It’s quite remarkable that multimodal imaging, which is imaging the brain using more than one modality like MRI, CT, or PET, can reveal a tremendous amount about how our brains are aging. There’s been a lot of research in the past several decades to integrate these techniques and help us to understand how our brains might be aging in ways that can predict our risk for disease. So, it’s pretty interesting that with MRI, you can map some very subtle features of the brain that can reveal the extent of atrophy, solely the extent of shrinking of certain parts of the brain.

With some functional techniques like PETs and other techniques, you can image the activity of the brain and get insight into whether there are deficits of brain activity that could be reflective of Alzheimer’s disease processes. This is one of the reasons why MRI and PET and these other imaging techniques have taken hold of the medical field in ways that help clinicians identify and diagnose persons with cognitive impairment, including Alzheimer’s.

Being Patient: What does an aging brain look like? Does everybody’s brain age in the same way?

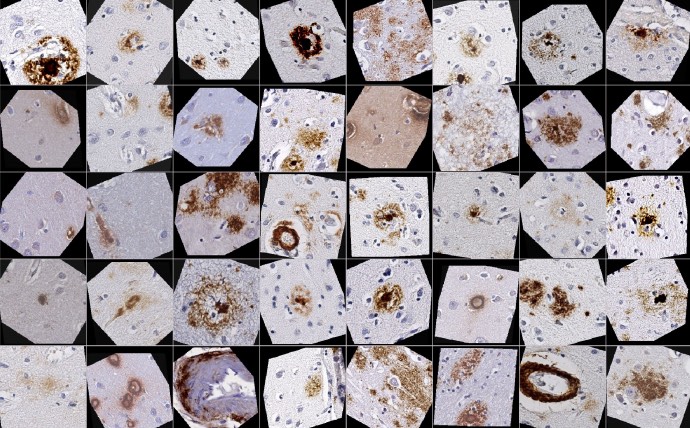

Irimia: In the aging brain, we typically see commonalities across most people. We see a phenomenon called atrophy, which refers to the shrinking of the brain matter. We also see something called ventricular enlargement. The ventricles are these fluid-filled structures in our brains that dilate with age as our brains shrink. So these and other features of brain aging are very apparent throughout most people. However, there are also abnormal patterns of aging that may be seen mostly in persons with the disease.

For example, in Alzheimer’s disease, we see tremendous changes in a part of the brain called the temporal lobe, where we see a lot of atrophy and a lot of shrinking. We also see this in the hippocampus, which is a structure in the brain that’s responsible for and involved in memory formation. So, there are patterns in the aging brain that can tell us a lot about the type of disease processes. We’ve been trying to leverage this as we developed our approach to estimating brain age.

Being Patient: You’re now using artificial intelligence to determine how brains are aging. What have you found out?

Irimia: What we found out is actually quite interesting. First, we found that different aging patterns are quite subtle in men versus women. Although there has been research on this before, we were able to identify some subtle patterns using our AI approach, and we could map across the whole brain. We could then use it to understand the sex differences better. So, that’s one thing we learned.

In Alzheimer’s disease, there is, as you know, a difference in risk between men and women. In the risk of Alzheimer’s, females are at higher risk for Alzheimer’s, and it’s not yet clear why. Using this AI tool, we also noticed that some of these differences are actually based on differences in sex that translate into differences in aging patterns that lead to Alzheimer’s disease. So, it seems that part of the reason Alzheimer’s is more frequent in females is perhaps based on the fact that the female brain ages a bit differently from the male brain. So, we found that very interesting.

Being Patient: When you say that women age differently than men in terms of their brains, what does that look like?

Irimia: Well, there is a very interesting phenomenon called laterality in the brain. In other words, certain brain functions rely more heavily on one side of the brain, such as the left side, compared to the right side. The fact that we are, for example, left-handed or right-handed is based on this kind of laterality.

We notice that some of the aging patterns and differences between men and women are due to this phenomenon of laterality. The dominant hemisphere is usually larger in a person, depending on whether they are left-handed or right-handed. We saw that it is actually atrophying slower in one sex versus the other, the subdominant hemisphere.

In other words, the part of the brain that’s not being used as much is actually more vulnerable to aging in men but not in women. So, the subdominant lack of a brain hemisphere will age a bit slower in women than in men. In the case of brain aging, it applies particularly to men because the subdominant hemisphere seems to be aging faster than in females.

So, there is this fascinating laterality effect that seems to be mediated by sex.

Being Patient: So, how does brain age relate to cognitive performance?

Irimia: Well, there are certain functions that we have examined. We have looked at how the brain’s aging patterns relate to cognitive performance patterns. We found that our AI tool was much better able to predict cognitive impairment seen in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease, much better than the actual chronological age of the person.

We hope this tool will be useful in estimating the risk for cognitive impairment much earlier than currently possible. That’s because we rely on identifying aging patterns, and aging starts very early in our 20s. So, we have a process that takes place across the entire lifespan and certainly across adulthood. If we can find these patterns of aging that extend throughout the middle age, that would be a tremendous help in identifying people who might be at higher risk.

Being Patient: Do all brains start to age around twenty?

Irimia: As far as we know, aging is a universal phenomenon in mammals, including humans. However, the rate of aging is very much variable from one person to the next. That’s one of the facts that were of tremendous help to us as we developed this AI tool because we relied on these differences in the pace of aging across individuals. We’ve seen how interesting it is to look at these differences and identify the patient’s specific aging profile. So, for example, with a healthy diet and plenty of exercise, the brain ages a bit slower. There are populations out there where, in fact, they’re getting so much exercise that their brains age very slowly.

“We hope this tool will be useful

in estimating the risk for cognitive impairment

much earlier than currently possible.”

On the other hand, some groups have brains that age much faster. For example, in alcoholism or drug abuse, the brain is aging much faster. In obesity, the rates of brain shrinking are faster as well.

Being Patient: When we have conditions like obesity, alcoholism, and drug abuse, is that reversible in our brains? Is brain aging reversible in these cases?

Irimia: The brain turns out to have a remarkable capacity for bouncing back. There’s been research suggesting that if these toxic habits are discontinued, the brain can gain some of its previously lost functions and recover to some extent. Now, some of the damage may very well be permanent, looking from case to case. But, the brain does have the ability to recover to some extent. Actually, it’s larger than we might anticipate.

What we saw in these individuals who have recovered from alcoholism and other similar conditions is that their brains start to atrophy. They start to shrink slower than they did while these individuals were alcoholics. So, it’s a very interesting phenomenon to map and understand.

Being Patient: Is the AI tool being used currently, or is it still being researched for its effectiveness in diagnosing or assessing brain age?

Irimia: This tool is available to the public from a website listed in the paper we published. It’s available to researchers and anyone who wants to try it out. What is needed to use it is a high-quality research-grade MRI scan and some pre-processing. So, it’s not quite the kind of tool that anyone can use readily, but it is available to other researchers worldwide and anyone who has the data and time commitment to analyze these brains. We made this public so that others can use our tool to learn and gain more insights about the brain, and we’re happy to do that.

Being Patient: Because it’s open to the public, if I get an MRI scan— does that mean I can upload my results, or do I need to do it through a doctor?

Irimia: So, what would happen is that you would need to download our software. A little bit of expertise is needed in learning how to run it, but it’s not very difficult for someone with some programming experience. That’s because it’s a software package with a programming-like interface, but it takes the MRI scan as input, with some pre-processing, and then generates a number. This number is the biological age of the individual whose MRI was uploaded.

“The brain turns out to have

a remarkable capacity

for bouncing back.”

It does not know the sex or the age or really anything about the person. Usually, it will guess fairly accurately in a person scoring cognitively normal. In individuals who have Parkinson’s disease or Alzheimer’s disease, it’ll actually be off by a number of years. The difference between the true age and the age predicted by the software is something called an age gap that tells us how much older the brain of that person is than expected for a cognitively normal person of that age.

So, for example, if you upload the brain scan of a 70 year old, who might have Alzheimer’s disease, and the software says that person is 75, then that means that the difference is 75 minus 70. Those five years are the extent of additional aging in that person due to the disease or other processes. So, this is five years. This is a brain that’s five years older than expected for someone of age 70.

Being Patient: We have a question from the audience. Does childhood trauma impact brain age? How much of the aging that causes Alzheimer’s is from environmental factors, and can we determine that through this tool?

Irimia: The tool can certainly be used to help studies of that kind. Other researchers have found that persons who went through trauma in their childhood are at higher risk for anxiety and depression throughout their lives and may even be at high risk for other disorders of the brain. It’s unclear whether they are at higher risk for Alzheimer’s. But in terms of the trauma in question and brain aging, we do need to do more research in that area, which we haven’t done yet. It is certainly a compelling hypothesis.

Being Patient: Do you have enough data to say how accurate this AI tool is?

Irimia: We’re very proud of the fact that of all the tools that have been developed to estimate brain age, ours is so far the most accurate. The average error in cognitively normal persons is about two years, so plus or minus two years is the average error. This is the best that one can get so far from MRIs. We’re excited because this is usually a much smaller error than is needed to quantify aging in persons with Alzheimer’s disease, where you have accelerated aging.

Being Patient: For those of us with loved ones with Alzheimer’s, would we be able to understand where they’re at within the stages of Alzheimer’s?

Irimia: Well, I think some of that can be mapped using our tool because the stages of Alzheimer’s are related to the extent of additional brain aging that the disease causes. I do believe there is a relationship between the amount of excessive aging, according to the stage of Alzheimer’s disease. Now, there is also the question of how the brain ages that we predict are related to the cognitive impairment extent and severity of the person. Our study has shown that we have very good agreement, especially in certain cognitive tests pertaining to certain aspects of cognition. We have excellent agreement between our predicted brain ages and the stage of Alzheimer’s in these individuals. However, we need to be careful because there is a lot of heterogeneity in this group, so we need to do more studies on that. We cannot always say with confidence that the software will capture things as well as on average in any individual or every single individual.

Being Patient: Could this tool help predict or diagnose different types of Dementia?

Irimia: This tool is probably not as helpful for differential diagnosis partly because we’re using MRIs. From MRIs alone, it is rarely possible to make a very accurate differential diagnosis of Alzheimer’s versus Frontotemporal Dementia, or Dementia with Lewy Body, and so forth. Usually, that kind of differential diagnosis involves a more comprehensive imaging and medical examination of the patient. So even with all the MRIs, we could use them to train this neural network, but this type of tool is not there yet. However, this is a very interesting question because to do this kind of differential diagnosis, using a tool like ours might very well be within the abilities of AI in general. We’re very interested in extending the capability of our software to do this kind of work. Still, we do need to acquire more data and have larger datasets to look at before we can say that we can classify patients according to diagnosis.

Katy Koop is a writer and theater artist based in Raleigh, NC.