A lifetime of unthinkable challenges prepared Brian Van Buren for his latest role as an advocate for members of the Black and LBGTQ communities living with Alzheimer’s.

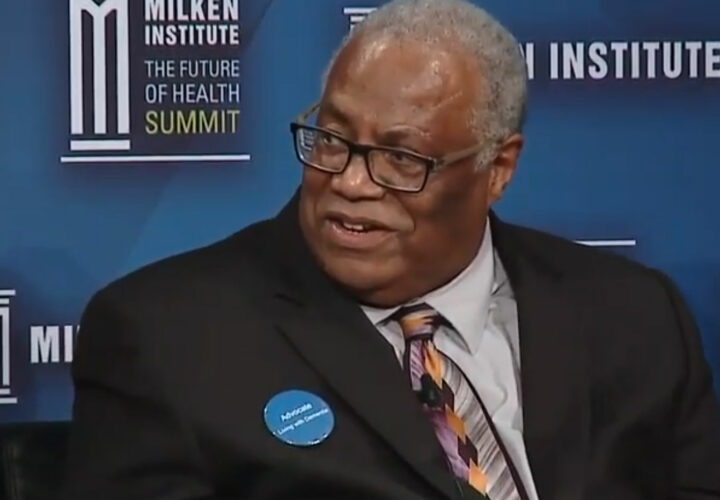

This article is part of the series Diversity & Dementia, produced by Being Patient with support provided by Eisai. Image courtesy of Brian Van Buren. Image: Brian Van Buren speaking on a Milken Institute panel in 2018.

No one would question Brian Van Buren’s forgetfulness in his 50s; after all, he was the survivor of multiple traumatic events that would shake anyone’s foundation. A survivor of childhood sexual assault by a priest, he had also lost first one partner to violence, and then a second to AIDS. His trauma was so impactful that he performed a dramatic U-turn mid-career, moving from licensed clinical therapist to flight attendant. So, a little forgetfulness — lost keys, missed appointments and the like — could easily be forgiven and overlooked.

It was a health crisis on his job as a flight attendant at age of 64, however, that finally revealed his forgetfulness was a sign of something else — something quite unexpected: Van Buren had early-onset Alzheimer’s.

“I was an international flight attendant and on a flight from Washington, D.C. to Brazil when I had a massive heart attack,” he explained. “They had to make an emergency landing in San Juan, Puerto Rico, where I remained for two weeks.”

After Van Buren’s release and return to his home in Charlottesville, North Carolina, he decided to take care of his physical health, including bariatric surgery to lose weight and help his type 2 diabetes. Before he could undergo the procedure, however, he needed a psychological evaluation, leading to some unexpected results. “The doctor was concerned because my cognitive ability was almost non-existent,” he said. “She referred me back to my GP, who ordered an MRI.”

That scan indicated vascular dementia, which led to an appointment with a neurologist. “He pretty much diagnosed me without even giving me a PET scan, but I did eventually receive one,” Van Buren said.

By 2015, Van Buren had his official diagnosis of early-onset Alzheimer’s. For some time, he lived in a state of denial. He was familiar with the fallout from dementia, after having cared for his aunt and mother, who both had Alzheimer’s. The prospect that he, too, had the disease, led him down a path of depression.

Finally, in 2018, after quitting his job, Van Buren brushed himself off and attended a workshop designed to help those over the age of 50 begin new life chapters. The course inspired Van Buren to take action. Just as he has his entire adult life, Van Buren followed a path of advocacy.

Made for the job

Because of his traumatic background, Van Buren came to Alzheimer’s advocacy with a ready-made skill set. After losing his second partner to AIDS, Van Buren joined the Ryan White Foundation in Los Angeles, where he lived at the time.

“I became chairman of the foundation, operating with a $180 million budget from the state of California,” he said. “I kept very active and ended up getting funding from the CDC and the U.S. Council of Mayors, too, to develop HIV prevention programs for minority communities. I started one in both Texas and Louisiana.”

Van Buren said that advocacy for people living with dementia — especially those of color and who represent the LBGTQ community — was a natural fit because he understands these cultures.

“There’s a general rule in the Black community that what goes on in the house stays in the house,” he said. “So often people will not share a diagnosis with anyone other than family members.”

Today, Van Buren is a founding member and former board member of National Council of Dementia Minds, and a member of the Dementia Action Alliance advisory board, where he makes the rounds to talk shows and conferences, putting a face on the disease for Black and LBGTQ communities. In an inspiring twist, he views his own diagnosis with a positive spin.

“I tell people that being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s is the best thing that ever happened to me because it gave me a purpose and a focus,” he said.

In his role as advocate, he advises people living with Alzheimer’s and caregivers to surround themselves with others.

“At some point you have to realize that this isn’t a curse, but you do need support,” Van Buren said. “It’s available — there are so many organizations today compared to 10 years ago, so there’s no reason not to get assistance.”

Because Van Buren is deeply involved in some of those organizations and has the support of others, he is able to remain living at home, on his own. Beyond his support network, he credits technology, like Alexa and Siri, and services like Uber and Lyft, with helping him maintain his independence.

At the age of 70, Van Buren has led a full life, including many unexpected plot twists. dementia isn’t slowing him down, however, as he continues to travel whenever possible, in addition to his tireless work on behalf of fellow patients.

“I intend to continue flying and traveling,” he said. “Having dementia doesn’t have to stop you from enjoying life.”

Susanna Granieri contributed to reporting