Palliative care physician Dr. Lynn Hallarman shares her own family’s journey caring for her late mother with dementia before and during the outbreak of COVID-19. She shares guidance on late-stage dementia caregiving.

The COVID-19 pandemic has taken a toll on all of us, but for people living with dementia and their families, the public health crisis has been an especially stressful period when it comes to managing care, finding down time for oneself and searching for safe ways of seeing friends and family. Such trying times, however, can also spur people to turn the responsibilities of caregiving into a journey of personal growth.

Being Patient spoke with Dr. Lynn Hallarman, author of The Great Escape—A Physician Confronts Family Caregiving During the COVID-19 Pandemic published in JAMA, about her family’s experience of caring for her late mother Paula as COVID-19 cases began surging last year.

Hallarman shared insights on caregiving strategies, the challenges she faced of balancing being a daughter and palliative care physician, and her memories of Paula throughout the different stages of dementia.

Being Patient: Can you share with us your mother’s situation when the pandemic began last year?

Dr. Lynn Hallarman: She was living in what I would call supported independence at age 92 in New York in an apartment. She had 24-hour [care] that she had actually had for years. When the pandemic started to take hold in New York — and it did so in a very dramatic way in Long Island — my family and I started to panic about how we would handle managing my mom’s care.

“Because you can’t remember doesn’t mean

you’re not who you are. You’re still who you are and

you’re a person, and these times that I had with my mother,

I cherish completely because she was still wonderful.”

We ended up in a rush moving her to live in New Hampshire, and my sister could be much closer. Unfortunately, as sometimes happens when people have combinations of frailty and dementia, it was a lot for my mom to have this move happen. She was confused. She had more trouble complying to things we were trying to do. To nobody’s fault, she ended up taking a fall, breaking a bone in her neck, and that triggered this whole rock-n-roller coaster of events that led to a hospitalization and lots of stress for me and my sisters — not being able to see her in the hospital and trying to negotiate all that.

We ended up, fortunately [and] miraculously, getting her out of the hospital. She subsequently died of complications of dementia about two months later in New Hampshire. That’s our rig-n-roll, rock-n-roller coaster that we went through at the end of her life. She died last year [on] June 1st.

Being Patient: Were there aspects of care that surprised you?

Dr. Lynn Hallarman: There were things that didn’t surprise me, but it was so surprising to actually experience them because I had been going through things with families for so many years. One of them is a real disconnect between what you experience in the doctor’s office and what you’re actually experiencing at home. Sometimes those things don’t align well, and it can be very difficult for families to navigate their daily life with managing someone who has advanced dementia and coordinating care.

“I wore my professional hat at the end quite a bit

because I was the chosen one in my family, being the doctor,

to interface with the medical field. It was exhausting and I

learned a lot about what people go through.

It’s made me a better doctor.”

There are all types of dementias. You can have Alzheimer’s dementia, which is the most common, but there are other types as well, and they all have sets of different things to watch for. I think you can get mixed up in trying to deal with the everyday of it, and not get what you need from the medical professional. I found that to be the case quite a bit. We didn’t get a coordinated plan for my mother until the very end where she had a few weeks of hospice. Then we got more coordination and communication.

Being Patient: Why is it difficult to coordinate care for patients with dementia?

Dr. Lynn Hallarman: I think one of the things that we don’t do well as a medical system is we don’t have a comprehensive coordination that all patients at any stage of dementia have access to. There are pockets of it. For instance, hospice at the very end will give you a very coordinated thing where there’s only one phone call. They’ll have the nurse come. It all is smooth. But before that, you often as a family member might have to call the primary care doctor and you might have to fill out paperwork to get a bed, and then call the place that’s going to deliver the bed. You’ll have a whole separate pharmacy plan that you’ll have to deal with.

Then if you need a home health aide, that can be extremely complicated to achieve unless you do something called a spend down to become eligible for Medicaid aid or you pay for it out of pocket, and that can be prohibitively expensive for many people. It can be about $18,000 a month for 24-hour care. As a family member, you have to navigate all these components pretty much on your own.

Being Patient: How can families tell if a loved one is in late-stage dementia and prepare for care accordingly?

Dr. Lynn Hallarman: ‘How do you know?’ is complicated and what I usually tell families is that you want to hope for the best, prepare for the worst all along. In the case of my mother, she has three daughters. It took us probably four years to get her to do basic planning. What we wanted her to do was a power of attorney for finances. When the day came [and] when she needed someone to write checks for her, my sister ended up being in that role.

You need to have a power of attorney for finances. It’s one of the first things I tell people, and it’s better if patients get to do this themselves. Once it’s out of a patient’s hands, then it becomes a whole rig-n-roll with the courts and with getting a guardianship.

Patients need to be helped early through figuring out, who do they trust to help them navigate the practical aspects of their life like finances? In our family, it was my sister. The second question is, ‘Who’s your healthcare champion?’ In my family, it was me, and my sister was a secondary. Early, we did a health care proxy, which is what it’s called in New York state. It can be called a durable power of attorney for health in other states. You want to get that done early.

“‘How do you know?’ is complicated and

what I usually tell families is that you want

to hope for the best, prepare for the worst all along.”

Being Patient: What are some factors that can lead to a quicker decline in dementia than before?

Dr. Lynn Hallarman: Sometimes, what propels people further in dementia is if they have other medical problems, [these problems] can trigger worsening dementia. In [my mom’s] case, she was prone to falling. She broke a wrist, a shoulder, a hip, over that year (2020). It was very hard to keep her stable. Her weight was starting to diminish a little bit which is also another sign of advancing dementia, and also her behavior was a little bit harder to manage. Her care in terms of having caregivers became a negotiation with her. We had to have strategies. I often had to be the bad guy in the middle of the night because my mother listened to me.

It started to get difficult, but she still had a life. Because you can’t remember doesn’t mean you’re not who you are. You’re still who you are and you’re a person, and these times that I had with my mother, I cherish completely because she was still wonderful. She was hysterically funny [and] very smart.

Something I did for myself, and I’m suggesting it for the audience, is I kept a picture diary of my mom. What I was trying to absorb was where she was functionally in these pictures, because when you’re going to see your primary care doctor, that’s what you want them to know. That is what’s going to determine how much help you need, what kind of planning you have to do. Doctors sometimes will go right to [issues] like blood pressure and medications, and you can forget what you need to tell [the doctor], ‘My mom is having trouble walking. We’re having trouble getting her to sleep at night. [We] can’t figure out how to get her to eat a healthy meal.’

These things need to be articulated to the medical professional, so they can say, ‘Let’s have you meet with the social worker, so maybe we can fill out an application to get a shower chair and all the things that you need.’

Find a way to tell a story through pictures. Write some notes to yourself, ‘We went out to lunch but she was unstable.’ This is what I did. I think this is a very helpful way to track stages in dementia in a humanistic way but also to help you look back and say, ‘I see, two years ago she was in much better shape than she is now.’

Want to learn more about clinical trials

for Alzheimer’s and dementia?

Check out the Lilly Trial Guide.

Being Patient: Can you share with us your mother’s transitions through the various stages of dementia?

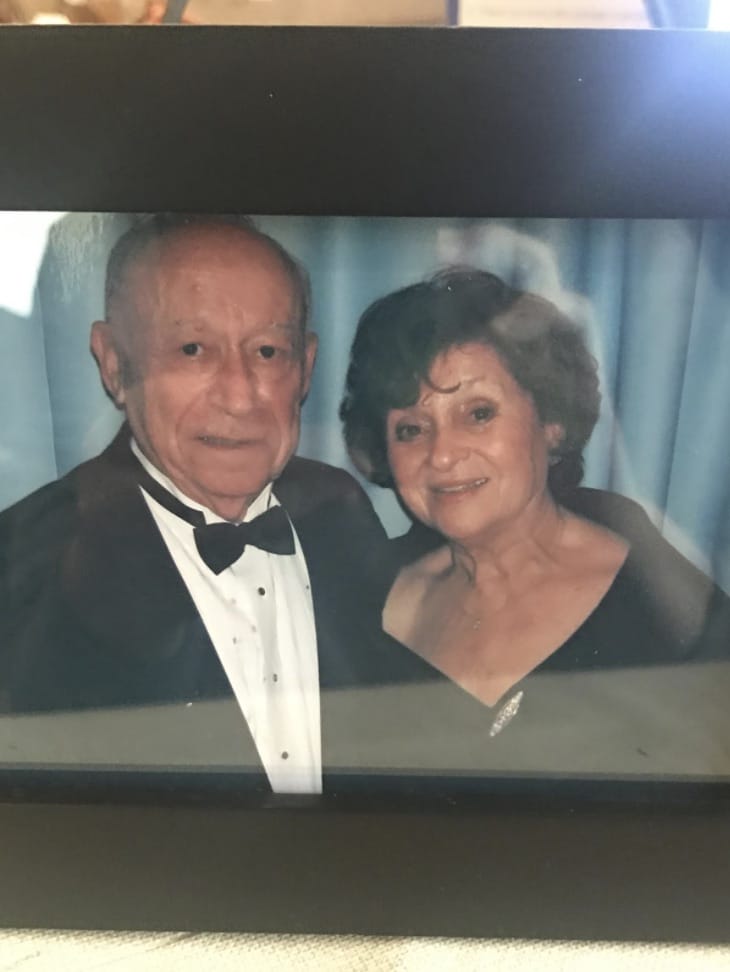

Dr. Lynn Hallarman: In this picture, she was in her 80s. She was a very robust, full of life, functioning individual, but around this time, we started seeing some signs that she was starting to have memory slips that are very common in early-stage dementia. This is one of the hardest things to deal with as a family.

My family took about a year of talking to each other on the phone, like ‘Have you spoken to Mom? Is she repeating [herself]? Is she forgetting?’ We couldn’t quite sort it out. It took quite a while to do that. I think one of the early mistakes families can make sometimes, or even patients themselves, is thinking that it’s all part of normal aging when we have problems remembering to the point where it’s impacting our daily function. The thing I always like to tell families is you’re looking at people’s memory and cognition, but you’re also at the same time looking at their function. In this picture of my mom, we were wondering. But she was very functionally well. She could do her day just fine. She didn’t need help with her day. She might have had the beginnings of a dementia at that time.

***

This is one of my favorite pictures of me and my mom. She was a little over 90 in this picture. She was not far from the end when I snapped this picture. She probably at this time had what the doctors would say would be a mild to moderate dementia by neurocognitive testing, because that’s something that doctors often do to determine someone’s stage of dementia.

Even though she might have been categorized as having a mild to moderate dementia, she was functionally at this point very impaired. We had full-time aides with her. She could not get through her day. She couldn’t give herself her medications. She could not drive. If you saw her there, she wouldn’t eat her salad. She ate the oysters. She loved oysters.

For people that start to advance with dementia, their eating habits can go all over the chart. They can start getting difficult about eating healthy foods. They often want to go for junk [food]. In my mom’s case — and we went out frequently because I wanted to be with my mother and she enjoyed this so much — she always wanted an alcoholic drink, which she never did when she was younger. I had to fool her with a non-alcoholic beer, which I didn’t like to do because I didn’t like to fool my mother. I’d like to respect my mother.

***

This [photo] is maybe not even a few weeks before my mother died. You would think she was just fine and dandy but, in fact, if you look closely, she was wearing a neck brace because she broke a bone in her neck. Even though she had a very optimistic spirit and she loved to eat, we were happy if we could just get her to eat cake at this point. My sister made her this cake. It had no special occasion.

She was showing some of the signs of what happens to people as they become more frail and more functionally impaired. In her case, to get her up off that chair, we had to have a strap around her waist, and we had to have two aides pull her up. She could walk with a walker, but it had to be with someone holding a strap behind her because she was so unstable. She wanted to walk, and if we let her, she would get up, and that was how she fell. She wouldn’t listen. She had a right, and she fell [while] getting some ice cream.

She was very frail. She had that neck brace, and this is what often happens to people with dementia: Something major happens and it sends you on a spiral because your reserve to deal with a medical catastrophe is not so good. In her case, when she broke her neck and needed this hard collar, her muscles in her chest and neck started to weaken and she already had weakened muscles from frailty and dementia.

What we know about dementia in the last stages combined with frailty [is people] often develop problems swallowing, because dementia is a whole body illness. It’s not just the brain and [people] can have other kinds of system failures. In my mom’s case and in many patients, they start to have trouble swallowing. They can choke and cough, and she had all of that before the fall. When she finally got that neck brace off, she couldn’t eat solid food anymore. She had microaspiration, meaning she kept inhaling things from her mouth, it could be spit and food, that would go into her lungs. It caused this chronic lung problem. That was part of how she died. It was this snowballing, which is what I would see over and over with patients with dementia. They would have diminished function that would lead to an infection, problems swallowing, something major, and after that it would lead to a death.

***

Being Patient: You’ve had a lot of experience as a palliative care physician caring for patients with dementia and families. Were you prepared for your own family’s experience?

Dr. Lynn Hallarman: I was and I wasn’t. So much of the time I just wanted to be a daughter, but it was very hard for me to let go of my palliative care hat. I have spent years and years helping families navigate through all stages of dementia. I felt that I had to be that person for my mother also. But that was difficult actually — I wore my professional hat at the end quite a bit because I was the chosen one in my family, being the doctor, to interface with the medical field. It was exhausting and I learned a lot about what people go through. It’s made me a better doctor.

All photos courtesy of Dr. Lynn Hallarman.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Contact Nicholas Chan at nicholas@beingpatient.com

I’m in a local support group , went to nursing school & cared for my father living @ our home, and now caring for my husband with progressing dementia. I very much appreciate this professional woman’s sharing her experiences & wisdom . Thank you very much.

I need to speak with Dr. Hallarman. My backstory and my offer is too long for this text box. Thank you and regards,

I’m a hha n I have a question what can you do with a non verbal dementia patient as far as theyre cognitive