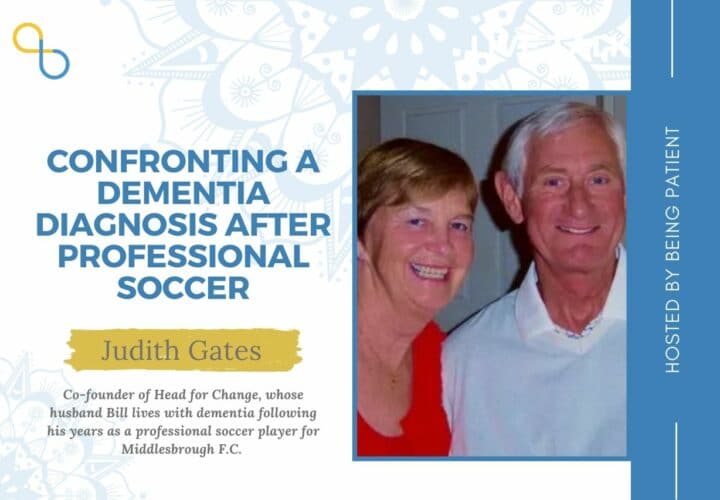

Judith Gates discusses her husband's dementia diagnosis following his years as a professional soccer player and how she was inspired to co-found the charity Head for Change.

There is growing recognition that repetitive head impacts increases the risk of CTE, a brain disease that can only be definitely diagnosed at autopsy. For the former professional soccer player Bill Gates, he was often exposed to head impacts as he was known for his headers during his time as a soccer player with Middlesborough Football Club. Decades after his retirement, he received diagnosis of dementia due to probable CTE. Being Patient spoke with his wife Judith last month about his professional soccer career and dementia diagnosis, as well as the mission of Head for Change.

- Bill was first diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment in 2014 and received a diagnosis of dementia due to probable CTE (chronic traumatic encephalopathy) in 2017.

- Head for Change aims to assist caregivers and families through hosting peer support groups and providing resources needed for practical issues such as financial and legal planning. It is also seeking to support independent research in the risk factors of head injuries and preventative measures to reduce exposure of head impacts.

- While Judith said sport governing authorities have been reluctant in recognizing the link between head traumas and neurological conditions, there are reasons for optimism. In parts of the UK, authorities have issued guidance on limiting headers in youth soccer. The UK Parliament also recently launched an inquiry into the long-term consequences of head injuries in sports.

Being Patient: Did Bill grow up hoping to be a professional soccer player?

Judith Gates: We come from the Northeast of England and the Northeast of England is a hotbed of football — what you call soccer in the United States. It was actually a priority for Bill when he was a schoolboy. It was a sense of self-esteem that he got from being a really good player. He was delighted to capture the England youth team at the age of 16 and to travel around Europe.

It was an important part of his life. In fact he was probably still among one of the youngest players to play for a league club before his 17th birthday. He played for Middlesbrough from 1961 until 1974 — 13 years with one club, 333 first team games at center back.

Being Patient: How was he exposed to head impacts during his career?

Judith Gates: One of the things that I remember clearly from his time playing was newspaper reports where the usual headline was, ‘Gates was strong in the air.’ He was expected to be the one who protected his goal at the time of corners, went up to the opponent’s goal when his team had a corner in order to try and get the ball in. He was known to be the one in the team that was the expert in heading. Obviously then if you have somebody who has a particular expertise, you optimize it. That was actually to Bill’s detriment. The Middlesbrough team trained everyday. He was expected in training to head up to 100 headers. He often saw stars, needed smelling salts and regularly suffered from migraines.

Historically, there’s a kind of joke in the United Kingdom about football that the trainers running on the field have two things. They have a magic sponge. It was supposed to relieve everything. They also carried smelling salts. The smelling salts were for use if people were dazed.

Bill had no outright concussions. His problems came from the repetitive head injuries, the ongoing blows to his head from repetitively heading the ball. He did report that to the club doctor, and the club doctor actually at that time was the England Club doctor so it was very much to the forefront of medical knowledge about the game. But when Bill reported his migraines to the club doctor, he was told, ‘this is just what happens.’ In fact, the debilitating effects of the migraines were the reason why he retired at the age of 30.

He could have gone on to play longer. His team was actually promoted to the first division, which was a big deal, and all of his footballing instincts would say, ‘Let me not retire at this time,’ but he recognized that the migraines were so debilitating that for his future health, he needed to make a decision. But that was not based on medical advice at the time.

While he was playing, he was studying accountancy. He was serving his articles, working for a firm of chartered accountants in the afternoons after training. That gave him a tremendous head start for life after football. He was able to take his accountancy knowledge and begin a business. He opened his first sports store just before his retirement. He built it up to a chain of 12 sports stores throughout the Midlands and Northern England.

Being Patient: Did the migraines continue after he retired?

Judith Gates: The migraines continued for about a decade after his retirement. They also went alongside mood changes, greater impetuosity, shorter attention span, shorter fuse for anger. At the time, you look at all of those personality changes and you think, ‘Is this the person? Is it the transition from being a professional sportsperson to being a businessman with all of the joys and the necessary worries?’ Retrospectively, in terms of looking at the life cycle of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, we recognize that these were probable indicators of the damage to his brain even at that age.

There was always an anticipation that he may suffer from dementia because the generation ahead of Bill in football, many of them did get diagnoses of Alzheimer’s, dementia, motor neuron disease and so on. Within the footballing family, we were aware that this was happening and putting that alongside Bill’s career as a centre back and his history of heading and migraines, Bill always anticipated that it could be a possibility. So, to a certain extent we were looking out for it. When the memory problems started probably in his early to mid 60s, there was an element where we thought, ‘Please don’t let this be the case,’ but there was also another element where we thought, “We knew this might happen, is it really happening now?”

The symptoms that he presented with were the ones that will be very typical to anyone who has a family member suffering from memory problems and dementia: Forgetting dates, forgetting times, forgetting things that you’re supposed to do, short-term memory issues of not being able to retain information, moving on to change in executive functioning, unable to plan activities and to work out what to do next and just a gradual deterioration.

This has been a 10-plus year journey from the very first symptoms, from a man who was can-do get-go, had built up a very thriving business in the United Kingdom, was never fazed by anything, thought that he could take on any challenge, to somebody who forgot what he was doing, couldn’t plan what he was doing, became increasingly dependent and reliant upon family members, and an absolute shadow of his former self.

Being Patient: Bill was first diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in 2014, what was the diagnostic process like?

Judith Gates: We went to see a neurologist in London. The diagnostic process included a brain scan and also included quite extensive cognitive testing and also physical testing. Ultimately, I was invited to sit in. At the time of the cognitive testing, it was extremely interesting for me as a former academic and educator to listen in detail to his responses and recognize things that I had previously glimpsed, but now see more clearly.

At the outcome of the array of tests, the diagnosis was given of mild cognitive impairment. I also clearly remember that the neurologist said your husband does not have Alzheimer’s or dementia. I remember a great sense of relief, thinking ‘It’s mild cognitive impairment. This could stay the same. It may not get worse. And I remember the sadness. Later that day, when we went to find the car that he had parked, we couldn’t find it because he couldn’t remember where it was.

That day is etched in my memory as a day in which I got further insights into his inabilities in thinking. I had a moment of hope when I was told he didn’t have dementia. Then I had an absolute crushing down of emotion when I realized that he could not function normally, and that there was the probability that this MCI would progress, which indeed it did.

Being Patient: In 2017, he received a diagnosis of dementia due to probable CTE. How did his symptoms progress?

Judith Gates: An exacerbating of symptoms in what can be a mild ‘I can’t remember what time we’re meeting,” then becomes ‘I can’t remember that I even have a meeting,’ then becomes ‘I can’t remember that I’ve been anywhere.’ It’s the gradual progression of things falling away.

My friend once described it as, ‘You have a tree in full leaf and then leaves fall.’ It’s a little like that. There are continual falling leaves until the tree right now, 10-plus years on, is almost bare. For example, Bill is now forgetting how to wash his hair, how to turn on a light. It’s a journey from knowing and being able to plan, towards not knowing and being unable to plan and being increasingly dependent.

Being Patient: What does probable CTE mean?

Judith Gates: The situation was that bill went for tests to seek to enroll in an Alzheimer’s research project. One of the tests was a PET scan with amyloid tracers. The neurologist was extremely surprised at the outcome from this because he essentially failed. He did not hit the borderline evidence of the level of amyloid needed to be in his brain for him to be a member of this research project. We arranged for Bill to have a spinal tap that would give an indicator of both amyloid and tau proteins.

The results of this test indicated that those amyloid levels were so far within the normal range, that the neurologist said I can’t give a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s. However, he does have elevated tau, which is indicative of a tauopathy of which CTE is one. He had no symptoms of any other tauopathy. And he had obviously potential for developing CTE given his sporting history. So we were given a provisional diagnosis of CTE, with the knowledge that you can only get a definitive diagnosis postmortem.

Being Patient: What inspired you to co-found Head for Change?

Judith Gates: When Bill was first diagnosed, I made two promises to him. One that I would help him optimize his life. The second was that I would try to be part of the solution in order to make sure that this didn’t happen going forward. The second promise was premised on the fact that that would be his legacy.

I was fortunate to meet with a couple of other people who have become co founders of head for change, and they share my passion and commitment, because they are family members also, of people who are suffering from sports-related neurodegenerative disease.

Each of us have a professional background. I’m a former academic as a university lecturer. One of our co-founders is a surgeon. Another of our co-founders is a very successful business woman, a company director. We wanted to bring both our professional knowledge and our personal commitment to found an organization that took as its strapline, took as its purpose to be part of the solution, an organization that seeks to protect the players, whilst also protecting the game and thereby protecting the future of both.

Being Patient: One of the goals of Head for Change is to provide support for families, tell us about some of the specific programs.

Judith Gates: Once we launched, we received many communications from family members who said, ‘We feel so alone. We feel that no one cares. We’ve been given a diagnosis and we are left to get on with it.’ One of the most poignant communications that I received from one person said, ‘I just need,’ and then she put several dots and said, “I don’t know what I need.”

For me, she was really highlighting the bewilderment on the part of the family members who are faced with the long goodbye, as it has been described, who are faced with practical problems of support, who are faced with mourning their partners while they are still alive because you are losing the person they were and you’re left with the shell. This actually really emphasizes the fact that we had set up to give care and support to family members, but we were recognizing the reality of it in the communication that we were having from family members.

We’re beginning our very first virtual support group. We are planning that to be a safe space for people who join us, a confidential space for people who join us, where they can share thoughts and feelings that they may be reluctant to share with friends because they’re trying to put on a brave face, maybe reluctant to share with other family members, because they’re trying to protect sons and daughters, but where they can share in an empathetic and cathartic way, what they are really facing our intention is very much to encourage people to give each other peer support, but we also have plans to bring in any experts that are necessary.

To go alongside that, we are launching our Head for Change kit bag, which is a collection of resources, links to organizations you may need to be involved with, pieces of information about what is sensible to do on a legal front or financial front and so on.

The emotional support from our groups and from our one on one, family friends will be matched with practical advice on things that need to be done. We hope by doing that, we remove the feeling of I am so alone, and that we also encourage people to look at positives on the basis of not everyday is good, but let’s find what’s good in everyday.

Being Patient: You’ve mentioned that it’s very important for your family to help Bill feel that he is valued and that he can still contribute. How is the family striving to achieve this?

Judith Gates: We’re striving to achieve it because he is still valued. He’s still my life partner, my son’s dad, my granddaughter’s granddad — much loved on all of those fronts. We’re trying to help him feel good by working with him and trying to see things through his eyes. For example, my favourite bit would be, historically Bill has always made a fresh fruit plate for the family. It’s his job in the morning and with guests as well. He gets the strawberries, the blueberries, the oranges out. He puts the number of plates out and he makes a fresh fruit plate. It’s become known as ‘Bill’s fresh fruit plate.’ He’s renowned for it.

We continue with that. What’s happened now is that I have to get the fruit out. I have to get the number of plates out. It was really sad for me just a week or so ago, I had to say to him, ‘You may be better peeling the orange with your fingers, Bill, rather than with a knife,’ because he’s forgetting how to do things. But what we collectively do is when the plate is made, we celebrate with him. We say, ‘Our fresh fruit plate. Bill’s fresh fruit plate. Thank you.’ Now that’s just one example, but we try to put that into everyday life. What he is able to do, we support him in doing and help him to continue doing it, and then we thank him for doing so that he has a sense of his personal worth, his ongoing contribution to the family to whom he has already given so much.

If I have one message that has been so helpful for me to other caregivers is try and look at things through his eyes. Once you do that, then it actually takes away irritation at repeating the same thing over and over again and it actually frees you to support him to do what he is still able to do.

Being Patient: What type of research is Head for Change aiming to support?

Judith Gates: We’re very much wanting to support independent research that is player centered and precautionary. One of the things that we discovered is that several of the research groups were funded by sporting governing bodies and many of the outcomes of their research took as a starting point the necessity of seeking absolute causation between sports related head injuries, concussions, sub-concussions, repetitive head injuries and subsequent neurodegenerative disease. When we talk about being play-centered and precautionary, we recognize that absolute causation is impossible, other than in a laboratory setting, and that in actual fact what research needs to demonstrate and is demonstrating strong associative links. The research that we are promoting is independent, in that it is not involved with sporting governing bodies. It is based on the premise of first do no harm, a sound medical basic premise.

We would be looking at the risk factors we would then be looking at the modifications that could be made to soccer and rugby that could protect the game but also protect the playeras. We would be looking at technological advances. We are also looking at lifestyle changes, ongoing monitoring of health in order to be able to intervene wherever possible. We’re looking at diagnosis, prognosis actions that could be taken during lifetime to prolong health, et cetera.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Contact Nicholas Chan at nicholas@beingpatient.com