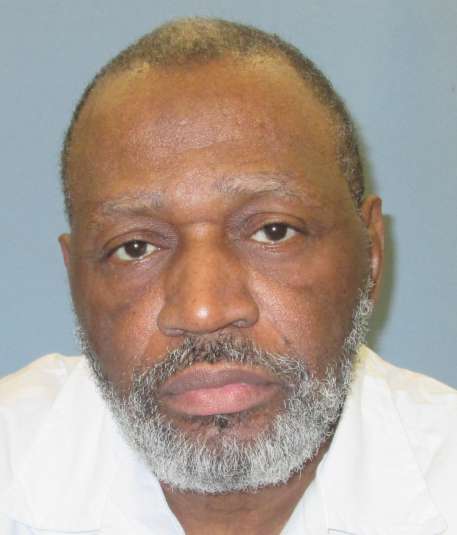

He's on death row. He doesn't know why.

Vernon Madison, 68, was convicted of murdering a police officer in 1985. Since then, he has sat on Alabama’s death row, spending the last 33 years in solitary confinement. But after two strokes that resulted in vascular dementia, Madison can’t recite the alphabet past the letter G, much less remember the crime he was sentenced to death for.

“Mr. Madison can’t tell you the season of the year. He can’t tell you the month of the year. He can’t tell you the day of the week,” said his lawyer, Bryan A. Stevenson, according to court documents.

Now, the Supreme Court is struggling to decide if failure to remember a crime and inability to understand the death penalty constitutionally excuses a person from the death penalty.

“If a person … simply is without memory of his commission of the capital offense, does that in itself render that person incompetent to be executed?” asked Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr.

Madison’s case represents what could be a bigger issue: With an aging population, many death row prisoners are in their 60s, 70s, 80s and beyond. “So this will become a more common problem,” Justice Stephen G. Breyer said.

It’s an issue the eight Supreme Court Justices are grappling with as they wait for Judge Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination to play out.

Precedent has been set in two previous Supreme Court cases that ruled an incompetent person who lacks “rational understanding” of their crime cannot be executed, as shown in Panetti v. Quarterman in 2007 and Ford v. Wainwright in 1986. But those defendants had mental illness, not dementia.

Madison’s lawyer agrees that just not being able to remember a crime is not grounds for excusal from the death penalty. But he argues that being incompetent—not being able to remember the circumstances that led him to the situation—should.

“It would have to be accompanied by some mental disability,” he said. “And here we argued that that disability was dementia.”

Madison is now legally blind and incontinent, according to his lawyer. He has trouble remembering where he is.

“Mr. Madison can explain to you that he has a toilet in his cell. It’s a 5-by-8 cell,” said Stevenson in court. “He can explain to you that he can use that toilet. But he routinely urinates on himself and he gets frustrated because he’s asking the guards to take him to the toilet. He’s not able to hold that memory of the location of the toilet next to his bed when it’s time for him to urinate, and so he continues to soil himself.”

Symptoms like that are common in dementia patients. But some of the Justices worried that extending the “rational understanding” ruling to dementia cases would open the door for other instances where memory falters. They asked whether blacking out might qualify as a mental disability, too.

“We’re not arguing that someone who is competent to stand trial, who nonetheless at trial maintains that they blacked out or don’t remember would, therefore, be incompetent to be executed,” said Stevenson. “What we’re arguing is something quite different.”

Stevenson maintains that Madison’s dementia renders him unable to grasp anything about the circumstances of why he’s on death row, meaning he “cannot rationally understand the circumstances of [his] execution, and executing [him] would be inhumane.

The state attorney prosecuting Madison, Thomas R. Govan, says that Madison does understand what a death penalty is, even if he can’t remember committing the crime. “On the things that matter, he does understand,” said Govan.

The court has not ruled before on a case of memory loss that stemmed from dementia. And while this case may set a precedent, even Govan ceded that “dementia exists on a spectrum.” Some people with Alzheimer’s or other types of dementia may have their long-term memories in tact, while others may not be able to carry out basic functions, like eating and drinking on their own. The state argues that cases of severe dementia would constitutionally prohibit execution.

Since the Supreme Court currently only has eight justices, a 4-4 split decision will typically result in upholding the previous ruling from the lower court, which found that Madison was fit to face the death sentence. However, in a 4-4 split, the decision does not create a precedent.

I don’t believe in execution on principle, but in this case I think it would be a blessing. What else would his future hold? Having a choice, I would welcome a planned ‘mercy death’ when I become helpless, and definitely once I am vegetative.