Listening to music at a World Rocks Against Dementia day, as well as hosting a food and clothes drive to raise money for homeless families are just a few of the activities seniors have participated in this year at Hope Health of Adult Day Care Center in Uganda. The center was founded by Isaac Turyahikayo, a Ugandan caregiver who helps vulnerable seniors in his area with dementia.

According to the Global Alzheimer’s and Dementia Action Alliance, 50 million people around the world live with dementia. More than half of these live in low or middle income countries, and 70 percent of the 130 million people set to have dementia by 2050 will be in the developing world. Alzheimer’s Disease International found that sub-Saharan African countries have the fastest growing elderly population in the world—predicted to reach 161 million by 2050—and by 2050, an estimated 7.5 million of them will have dementia. The cost of dementia in sub-Saharan Africa is already about $6 billion USD and resources to meet the growing demand are limited; as the elderly population expands, and costs grow, the toll on caregivers and health services alike could be huge.

To learn more about the impact of dementia on caregivers in Africa, we spoke to Isaac, who opened Hope Health of Adult Day Care Center to help seniors who are disabled or suffer from dementia and to eliminate the stigma of an Alzheimer’s diagnosis, something he says is still a large issue in Uganda.

Q: “Tell us about Hope Health of Adult Day Care Center and the people who attend your center.”

A: Our center opened in 2016 and supports people who are part of Uganda’s aging population by providing them with food, medical care and a place to do daily activities. Initially, we were in another building, but that did not have a strong foundation; it was often affected by bad weather, including flooding, which was not good for elderly people, who get sick more easily. We moved into our current building in early 2017.

There are 46 people who attend our center and six people on our team. The residents stay for breakfast, lunch and sometimes evening tea. In the evening, volunteers escort them back home. Most of these people are poor and more than half of them suffer from dementia. They are also grandparents who have become caregivers for orphaned children, since some of their sons and daughters passed away from HIV/AIDS.

Q: “So even though some residents have dementia, they are also caregivers for their grandchildren?”

A: Yes. We meet children who look up to their grandparents, since they no longer have parents. However, their grandparents can no longer work, so they often can’t afford to take these children to school. About 25% of the Ugandan aging group have medical insurance, but 75% do not, so we try to help them.

Q: “What inspired you to open your center?”

A: I lost both of my parents when I was six years old. After that, my aunt started taking care of me. However, as she began aging, I had to start looking after her. She developed a disease [dementia]. I was only about 16 or 17 years old, but when we went to the hospital, I learned a little information about dementia from volunteers there. They informed the hospital about this disease. They gave me advice on how to look after her, including helping her with feeding, but then she passed on. I realized many people are in this situation, and there was nothing being done. So I became interested in addressing this issue and creating awareness about this disease to inform the public about it.

Q: “How do you keep your center running?”

A: We [the residents and staff] started a small garden and grow crops, such as Irish potatoes, cabbage and spinach. Our residents eat the food that we grow for lunch and bring some home for dinner. Then, we sell the surplus food, as well as handicrafts that we develop with residents, at a local market. The funds we raise from agriculture and these crafts help pay for their medication and our rent. Eventually, we hope to raise money for a vehicle we can use for transportation. Some of our residents have to walk long distances to get home or to the hospital, which is challenging when it rains because we don’t want them to get sick.

There is a church-run hospital nearby called Rugarama Hospital that gives people who attend our center a 40% discount for their medication because our residents are part of a vulnerable population. Other than that, we do not have outside assistance.

Q: “What are some obstacles you have faced while trying to spread awareness about dementia in Uganda?”

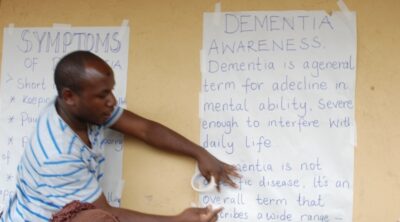

A: Although many people have the disease here, awareness is still low. People used to think that dementia was just a form of madness in aging groups. Can you imagine? They would see parents starting to forget their sons or daughters and say, “This is just madness,” not knowing that it is a disease. I want us all to stop using these terms.

Q: “What solutions would you propose for raising more awareness about dementia in Uganda?”

A: The government needs to get involved. We need to be supported so that we can reach far. Our country is big. I’m working in the western part of the country in my district to raise awareness, but in those districts where I can’t reach—what is going on there? The government planned to give a small wage of around $7 per month to each elderly person (someone who is 65 years of age or older), but that is very small. They proposed this idea two years ago, but it has never been effective. The system did not evolve because our population is so large.

My team and I visit local communities twice per month to raise awareness about dementia and to help caregivers; we teach them about their loved ones’ health, how to feed them and make doctor’s appointments so that they can get medication. However, many of these people live in poor communities, so we often have to give them food as well when we visit.

Right now, we are talking to local and church leaders who are also trying to help us spread awareness. We also want to introduce programs in schools so that children can learn about dementia. Everything is for the benefit of the community and the health of the people.

Q: “Do most of the doctors in your area know about dementia?”

A: Yes, though some do not have information. I try to meet with them so they at least have knowledge about what they do not know. Sometimes, they describe a patient’s symptoms, and I tell them that the patient likely has dementia. Even when I visit communities, I can usually identify if someone has dementia. Then, when I get this person to the doctor, the doctor finds out they have this condition.

Q: “What is one of the main lessons you have learned about dementia from your work, and what advice would you give to caregivers who have a loved one with dementia?”

A: I would tell caregivers to know that dementia affects each individual differently. That’s the most important thing that has helped me: learning about each person and responding to them differently, based on their behaviors. For example, when greeting one person, I may need to lower my voice so they feel comfortable.

Q: “What are some future plans you have for your center?”

A: Right now, we have a lot of activities for people who attend our center. We make crafts, sing, garden, put on plays and do community walks. Someday, I hope to get a TV and a computer for them. This way, residents can discover new information or maybe even connect with people who are suffering from the same condition to make friends. We also hope to construct a home for them so they can have accommodation. Hopefully, we can have our own clinic with a special residence for dementia patients.

Q: “What is something you wish others knew about the challenges you are facing as a dementia caregiver in Uganda?”

A: Because there is little awareness about dementia here, there is often no government funding. When people do not have information about what they are suffering from, they end up dying in hospitals or in their homes, even if they may have lived longer. The government here could care less. But we shall keep on. We try to help our aging groups get the right treatment and care, and we join hands to train caregivers.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

I were invited by Henry stuart to visit his project, but funds is my problem. He passed away Easter week-end. Ill be praying for this project. So wish I could do more. Blessings.

Isaac, the world needs more wonderful people like you! One of the most common complaints from caregivers in the United States is isolation. Both people living with dementia and their caregivers need a loving, supportive community.

Thank you so much Sandra. It is so challenging here in my country Uganda and Africa at large .

Hi Isaac ,

My name is Amina am from UK and currently completing my masters in occupational therapy.

I would like to speak to u as I am interested in your work you please do contact me .