Should healthy people take an Alzheimer’s blood test? Clinical guidelines say no. But Quest Diagnostics, one of America’s largest medical diagnostic companies, seemed to push a different idea.

Should healthy people take an Alzheimer’s blood test? Expert consensus says no. But Quest Diagnostics, one of America’s largest medical diagnostic companies, promoted annual asymptomatic testing.

Blood tests to screen for Alzheimer’s biomarkers could be a game-changer: High-quality tests may help doctors make a diagnosis sooner without expensive, invasive diagnostics, breaking down barriers to access new anti-amyloid drugs or join clinical trials. Here’s the thing: These tests aren’t for everyone. Experts only recommend using these blood tests — including one recently approved by the FDA — in people with cognitive symptoms.

Quest Diagnostics, one of America’s largest medical testing companies, has a different idea. Their AD-Detect Test, which measures the ratio of Aβ42 to Aβ40 proteins, has been marketed for annual screenings in cognitively healthy people.

This test has become somewhat infamous among neurologists. When it was first released in 2023, anyone could order AD-Detect without a doctor’s oversight. In response to backlash from experts criticizing the direct-to-consumer offering as irresponsible, the company started requiring clinical involvement. Today, AD-Detect can only be ordered with a doctor’s supervision.

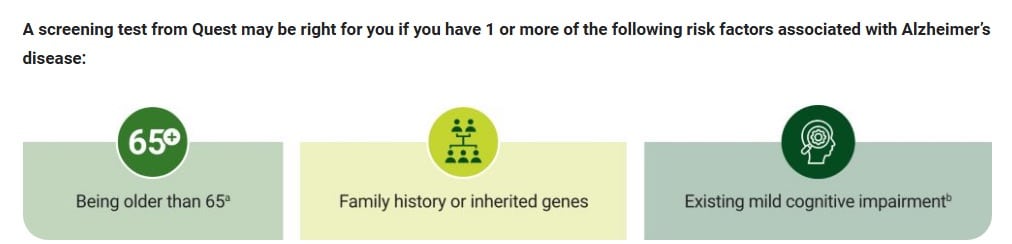

But were doctors — and patients — getting clear information on who the test is right for? Patient-focused messaging remained on Quest’s website until last week that the test was appropriate for anyone who had one or more of the following risk factors: being over 65, having a family history or genetic risk factors for the disease, or being cognitively impaired. “It can help you and your doctor establish a baseline and, if used as part of an annual screen, assess change over time,” Quest’s marketing messaging read.

In other words, almost anyone could take the test if one of their relatives had dementia, so long as they have $400 and shop around to find a doctor willing to place the order. Further, experts say, the test may not be accurate enough to be clinically useful for any audience.

In an interview with Being Patient, Quest Diagnostics Medical Director for Neurology Dr. Michael Racke said that the Global CEOi guidelines do support asymptomatic testing. “If you look at several different organizations and what they suggest regarding biomarker testing, you’re going to get lots of different answers,” Racke told Being Patient. “There’s groups like the global CEO initiative for Alzheimer’s disease that says you should test people already at age 55.”

But experts say Quest pitching the test for patients without cognitive symptoms is problematic. According to scientists including Dr. Suzanne Schindler, a dementia specialist at Washington University, St. Louis, and the first author of the guidelines, Racke is misinterpreting her guidelines.

“There are significant risks associated with testing of asymptomatic individuals,” Schindler said. “We do not normally manage cognitively unimpaired individuals and testing these individuals decreases our capacity to see patients who do have symptoms and might be eligible for amyloid-targeting treatments.”

Charlotte Teunessen, a professor at Amsterdam University Medical Center in the Netherlands and a leading expert on Alzheimer’s biomarkers, also found Quest’s positioning of the test to patients and doctors problematic. Teunessen told Being Patient that encouraging healthy people to take clinical steps to see whether or not they have Alzheimer’s biomarkers is “wrong” and contradicts “several clear guidelines” developed by experts including the World Health Organization, the Alzheimer Association, and the International Working Group.

Even Quest appears to be second-guessing this position. The aforementioned website messaging, archived here, was taken down during Being Patient’s reporting this article. When asked about the intended audience for AD-Detect, Quest spokespersons took a clearer stance than medical director Racke or their site: “The AD-Detect tests are intended for testing individuals that have symptoms,” they said in an email. “Messaging to individuals that are not healthcare professionals should be limited accordingly.”

Can early notice of Alzheimer’s biomarkers make a difference?

The company suggests doctors use this test as part of an annual screening to see how the ratio of a certain kind of beta-amyloid proteins that build up in the brain and foreshadow Alzheimer’s — Aβ42/Aβ40 — change over time.

Quest’s Racke claimed the test is useful because it can identify cognitively healthy people at risk of eventual Alzheimer’s symptoms, and give them more time to improve their lifestyle and potentially delay the onset of the disease. Healthy lifestyle — factors like exercise, diet, and quality sleep — has been linked to lower dementia risk. “There’s no FDA-approved treatment yet for them, but potentially they could make lifestyle modifications that could potentially reduce their risk,” Racke said, noting that changes in lifestyle could help bring these biomarkers back to normal levels. But third-party scientists say this is a bit of a leap in logic: There is no solid evidence as of now that a cognitively healthy person can actually reduce their beta-amyloid or tau levels through lifestyle modifications.

Stretching to make the case, Racke pointed to a small study of 50 participants which showed this might be possible in a different audience — people who already have Alzheimer’s symptoms. But there are issues with this study, too: The study found that an intensive intervention combining diet, supplements, exercise, and other interventions lowered the levels of beta-amyloid build-up in people who already had mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s. Not only is this a different audience; scientists have criticized this particular, small study for its flawed methodology, while pointing out that it was run by Dean Ornish, who has a commercial conflict of interest: He sells an expensive lifestyle intervention course he says can “reverse” dementia.

Racke also cited the FINGER lifestyle intervention trials to make his point. These trials found that a plethora of healthy changes in concert may delay the onset of Alzheimer’s, and they’ve now incorporated blood testing into their methodology. However, the FINGER trial team has not published any data to indicate that lifestyle changes make any difference when it comes to blood biomarker levels.

“Blood biomarker levels change very slowly over time, and there is no evidence that checking them repeatedly would be helpful,” Schindler, the guidelines author, clarified.

Is Quest’s AD-Detect test accurate?

Aside from the marketing approach, experts told Being Patient they think Quest’s test is not up to snuff from a technical standpoint: According to the same guidelines that Racke says Quest’s testing aligns with, the Aβ42-40 test isn’t adequate for use in primary care. The guidelines focus on two numbers: sensitivity and specificity.

In blood tests, these two metrics both refer to accuracy, and in this case, sensitivity measures how well the test identifies individuals who do have Alzheimer’s biomarkers (true positives), while specificity measures how well the test identifies individuals who do not have Alzheimer’s biomarkers (true negatives).

The guidelines Racke referenced throughout the interview suggest that tests should meet two benchmarks: ≥90 percent sensitivity, and ≥85 percent specificity. Quest succeeds in the sensitivity category, with a sensitivity of 93 percent. But when it comes to specificity, the Quest test fails to meet the mark by a notable margin, performing at 74 percent. This means a higher likelihood of “false positive” test results.

This outcome has so far been seen in early research: In a study that has not yet been published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal, Quest checked how well their blood test worked in a population of 215 older adults who visited a memory clinic. The people who visited the memory clinic were different from the average 65-year old — they had memory complaints already and were more likely to have beta-amyloid plaques than healthy older adults in the general population. According to brain scans, almost half of these 215 people had beta-amyloid plaque build-up several times higher than in the general population. But because of the low specificity of Quest’s test there were indeed high rates of false positives: One in four people without the Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid biomarker received a positive result anyway.

The pitfalls of false positives

Experts caution that the wide use of these tests would lead to a lot of false positives, and that inaccurate results could lead to unnecessary and expensive medical testing and stress. Being Patient spoke to three dementia specialists with expertise in biomarker testing about Quest’s test. None felt it was suitable for clinical practice for this reason.

“I do not think having inaccurate information is helpful,” said Schindler. “False positive results result in healthcare burden and costs that would not be necessary if more accurate tests were used.”

Schindler added receiving a false positive result from an Alzheimer’s biomarker test could potentially make people ineligible for certain types of insurance coverage or lead to employment discrimination.

Because of the test’s shortfall when it comes to false positives, Dr. Joseph Therriault, a PhD candidate at McGill University, called it a “low-quality test” that doesn’t provide helpful insights to doctors. “I do not recommend this test to consumers, and I do not recommend that clinicians order this test either,” he told Being Patient.

But Racke suggested in an interview that people who receive a false positive are actually at 15-fold higher risk of becoming positive via an amyloid-PET scan in the future, a sign of Alzheimer’s disease.

“There’s going to be plenty of people who are considered to be false positives for the test, because they’re negative for the PET scan,” said Racke. “But if you follow those people over time, those people compared to somebody who is negative for Aβ42/40, have a 15 fold increase and [are] likely to become PET scan positive.”

Even if a person receives the false positive, Racke thinks it’s still meaningful. “Even if it’s a false positive, I would argue it’s not really false,” he said. “If you follow those people over time, they become true positives.”

Being Patient followed up after the interview to ask for a specific study for that claim. Schindler said that studying false positives could be an interesting avenue for researchers, based on her study, but that “the clinical value of this result is unclear” and that it does not justify using tests with high-rates of false positives.

Other experts were skeptical of Racke’s claims as well: “There is no scientific evidence for his statements,” Teunissen said.

Who are Alzheimer’s blood tests right for?

While several experts agreed that Quest’s Aβ42/Aβ40 blood test doesn’t meet the mark for use in the clinic, as set out by expert guidelines, there are other blood tests on the market that do. While they make it easier than ever to measure biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease, the tests are only useful in specific situations and are intended for use alongside other diagnostic tests — not as stand-alone tools.

After a doctor or dementia specialist has ruled out any other potential causes of cognitive decline, the test could be used instead of or alongside other biomarker testing, like a cerebrospinal fluid test or amyloid PET scan to confirm the presence of beta-amyloid plaques to determine if someone has Alzheimer’s.