A recent analysis of early-onset dementia data found that rates of the illness are higher than previous estimates, but researchers aren’t ready to sound the alarm bell just yet.

Early-onset dementia — sometimes referred to as young-onset — has long been a puzzle for doctors, scientists, and researchers alike. Initial symptoms of the illness, which affects people aged 30 to 64, don’t match established norms of what dementia looks like and people are often misdiagnosed or diagnosed too late. But that’s changing, and could explain why a recent report found that the global rate of early-onset dementia is higher than previous estimates.

A review from Stevie Hendriks of the department of psychiatry and neuropsychology in the School for Mental Health and Neuroscience, Alzheimer Center Limburg, at Maastricht University in the Netherlands, and colleagues analyzed dozens of studies that, together, determined the rate of early-onset dementia is 119 per 100,000 population.

The review acknowledges its limitations — underrepresentation of African countries, low-income countries and upward-biased estimates because nearly half the studies focused only on people 60 to 64 years old. However, even with flaws in the data, Hendricks and his team hope their analysis changes the medical community’s approach to this illness.

“This should raise awareness for policymakers and health care professionals to organize more and better care for this subgroup of individuals with dementia,” they concluded.

The findings are left open for interpretation, with the authors offering no clear conclusion as to why previous estimates were incorrect: Were they just historically underestimated, or is early-onset dementia actually increasing?

The answer could be as simple as these data sets were not yet combined and analyzed as a whole or more complex, taking into account when and how people are diagnosed and which populations are included in studies.

Arman Fesharaki, a behavioral neurologist and neuropsychiatrist and an assistant professor at Yale School of Medicine, who was not involved in the study, attributed the new estimates to improved screening tools, as well as a better understanding of environmental risk factors, like chronic substance use and an increase in traumatic brain injuries.

“We have a cadre of assessment tools that can be employed in everyday clinical settings, which in addition to comprehensive clinical and neurocognitive assessments, include highly sensitive MRI brain imaging… [and] PET brain scans using different ligands,” Fesharaki told Being Patient.

He noted that testing abnormal levels of specific proteins as well as testing for specific genes that help determine a person’s risk of developing a particular type of dementia also lead to early detection. These tests are constantly improving, especially with respect to genetic markers for dementia, and could be the reason for increased prevalence. So, it’s not that the world is suddenly facing an epidemic of early-onset dementia, but that our ability to diagnose, study, and treat it has drastically improved in recent years.

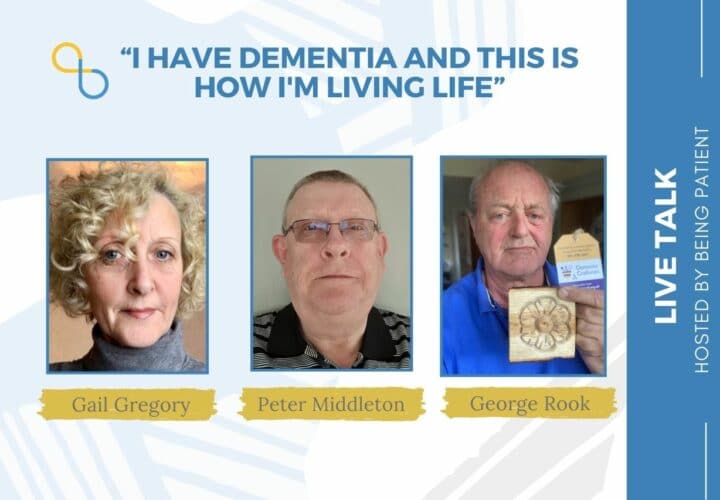

Fesharaki’s assessment supports stories shared by individuals diagnosed with early-onset dementia, who attribute poor diagnostic tools and a misunderstanding of how the disease presents in younger patients to their delayed or misdiagnoses. In one LiveTalk with Being Patient, Peter Middleton said the diagnostic process took nearly two years, and, for Gail Gregory, about 12 months. Gregory shared, “I had been suffering from depression a couple of years before I was actually diagnosed. I told the doctor then that it wasn’t depression [that led to my cognitive symptoms]. I knew there was something else going on. They sent me to a counselor and every time I went to the counselor, I said, ‘Sometimes I feel like I’m going mad. This is not depression. This is something totally different.’”

Middleton and others were also presumed depressed or anxious before correct testing determined they’d been living with early-onset dementia. Often, this is because doctors don’t know what they’re looking for. For instance, memory loss may be less prominent in people with an early-onset version of the illness.

Instead, it manifests as a drop in concentration, motivation, and productivity, which are also associated with depression. People also struggle with word recall in conversations, coordination and clumsiness, and visual perception. Some of these symptoms might be ignored or attributed to other issues, like sleep quality or diminished eyesight. If specialists aren’t familiar with the signs of early-onset dementia, some people can wait up to four years to be diagnosed.

The main takeaway is actually a hopeful one: Health professionals are getting better at spotting and diagnosing early-onset dementia and that, according to Fesharaki, also means access to a greater number of clinical trials aimed to treat the illness. And while this diagnosis may feel scary, the increase in people living with early-onset dementia also means there are more people and their caregivers with whom to find community and support.