Researchers at Boston University found that zapping specific regions of the brain in healthy adults over 65 could lead to improvements across experimental memory tasks. So far, it’s unclear whether these improvements translate to real-world tasks.

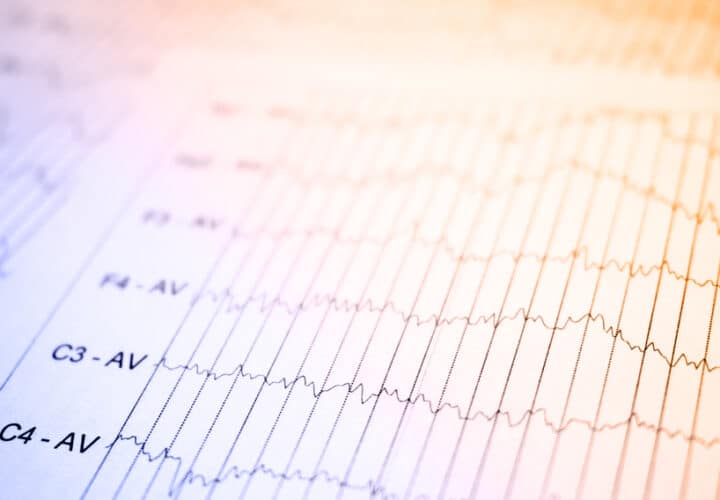

Every second, the 100 billion neurons in your brain fire off five to 50 electrical messages. This encodes instructions that are important for everything that the brain does, especially forming and consolidating memories. The flow of electricity coordinates connections between individual cells so that you can remember your spouse’s birthday, the last movie you watched, and your child’s high school graduation.

Scientists are now studying whether zapping specific brain regions with electricity could boost the brain’s ability to make memories. A study published in Nature Neuroscience used transcranial alternating current stimulation over the course of four days to boost working memory and long-term memory in a group of 150 healthy adults aged 65 to 88.

In the study, researchers hooked electrodes up to participants’ scalps and then had them try to remember 20 words they’d just heard aloud. Over the course of the exercise, their brains were gently zapped with jolts of electricity. After a few days of participating in the exercise, their ability to remember the list of words improved.

The improvements the researchers noted weren’t just on the day of. In fact, they sustained a month later, when the participants were retested. Think of this like learning to play a video game in virtual reality: At first, you struggle to make it through each level. After a few days of practice you get better, but then you take a break. When you pop the virtual reality helmet back on a month later, you still retain the memory of how to play that particular video game.

An important caveat, however, is that it’s still unclear whether this memory boost will hold up outside of the lab, in real-world tasks. You can imagine that playing Mario Kart in virtual reality doesn’t translate so well to driving in real life, where one needs to avoid pedestrians instead of banana peels.

Robert Reihnart, an assistant professor at Boston University was the principal investigator on this study. It builds upon previous work conducted by his team in 2019 which found that 25 minutes of electrical stimulation could temporarily improve memory in a small cohort of older adults.

“Existing therapeutic approaches for impaired cognition are limited by mixed treatment outcomes, slow improvement, and accompanying risks and side effects,” Reinhart told Neuroscience News. “For those reasons, there’s an urgent need to develop innovative therapeutic interventions that can provide rapid and sustainable improvements with minimal side effects.”

Putting on a thinking cap

To stimulate the brain, the researchers used a method called transcranial alternating current stimulation, delivered through electrodes on the surface of the scalp.

Over the course of the reading task in the study, which took 20 minutes on average, electrical stimulation was applied to the participants’ brains through the electrodes. For some participants, the electrical stimulation was directed to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex — a region of the brain associated with memory and other complex cognitive tasks. Other participants received stimulation targeting the inferior parietal lobe which is important for working memory.

After four days of this protocol, the participants were better able to remember the words from the beginning of the list — a sign of improved long-term memory. They were also able to better remember the words at the end of the lists after inferior parietal lobe stimulation — another sign of improved working memory. People who had worse levels of general cognitive function at the start of the study showed the greatest improvements by the end.

To test for the placebo effect, the researchers could use the wrong frequency of stimulation or zap the wrong parts of the brain. This did not boost memory for any of the participants. One month later, when scientists ran the same experiment, they found that the boost in memory was sustained.

Could this help treat memory impairments in Alzheimer’s?

Some experts were intrigued by the study, but they were cautious about interpreting its clinical importance to Alzheimer’s and whether the improvements translate to everyday tasks.

“We have to bear in mind, though, that the effects on memory were of the order of remembering three to four more words out of a list of 20, but this improvement in memory ability was detectable one month after stimulation which is quite remarkable,” Masud Husain, professor of neurology and cognitive neuroscience at the University of Oxford, wrote. “Whether these improvements would occur for everyday memories, rather than just for lists of words, remains to be tested.”

Another limitation of the study is that although the participants showed cognitive improvements, they were receiving brain stimulation during the memory task. It is unclear whether they’d perform as well without the boost.

Dorothy Bishop, professor of developmental neuropsychology, at the University of Oxford wrote that the study was overhyped.

“There is no indication that the beneficial effect would extend to everyday activities performed when no brain stimulation was taking place, such as those described in the press release,” she said.

Nonetheless, Reinhart and his team of researchers remain optimistic.

“We’re hoping that we can extend upon this work in meaningful ways and contribute more information about how the brain works,” the study’s lead author, Shrey Grover, a cognitive neuroscientist at Boston University, told Nature. The team’s future research will focus on figuring out whether this technique could help people with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease.