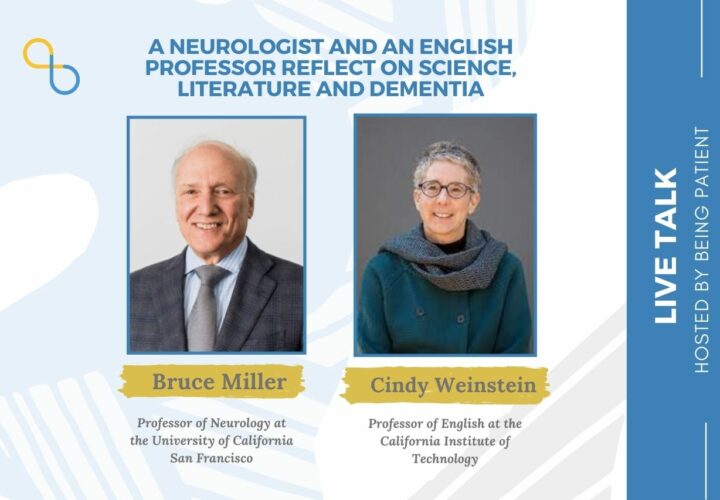

Being Patient speaks with Cindy Weinstein and Bruce Miller, authors of 'Finding the Right Words: A Story of Literature, Grief and the Brain,' about the Alzheimer's diagnosis of Weinstein’s father, and how writing, literature and neurology can enrich our understanding of dementia.

In the 1980s, when Cindy Weinstein was a graduate student of English, developing her expertise in language and literature, her father Jerry, now deceased, was losing his ability to read, speak and write as he grappled with Alzheimer’s. As Weinstein writes in her new book Finding the Right Words: A Story of Literature, Grief and the Brain (Sept. 2021), the irony was inescapable.

In the process of writing the book with her co-author neurologist Bruce Miller, Weinstein realized that she had buried her memories of Jerry. In writing, she shares, she was also sitting shiva, a Jewish tradition of mourning the death of a loved one, once again: “I can now remember my father without wanting to dissolve, and I have even retrieved some very happy and funny memories along the way,” Weinstein, now a professor of English at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), writes in Finding the Right Words. “They are no longer fossilized. They have come alive in a series of chapters about diagnosis, language, spatial disorientation, behavior and memory.”

Being Patient spoke with Weinstein about coping with her father’s illness during graduate school in her 20s, and how the process of writing the new book allowed her to reclaim her memories of her father nearly four decades later. Also joining the conversation was Miller, professor of neurology at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), who talked about the science behind dementia and the importance of understanding the stories of the families it affects.

Being Patient: Cindy, you found out in 1985 that your father was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, and he passed away in 1997 at the age of 70. What inspired you to join forces with Bruce and publish this book now?

Cindy Weinstein: I always wanted to write a book about my father and didn’t quite know how to do it. What I did know [was] I didn’t want to write the book alone, in large part because I felt like I had lived with the pain of his disease alone in a certain way. Even though as an English professor, I spent a lot of time alone writing books, this one was going to be different and I knew it.

I was so lucky to find Bruce because he could explain the neurology behind many of the symptoms of my father’s illness in a way that a general audience would be able to understand. One of the greatest challenges was figuring out how to get Bruce to agree to write the book with me, and also being able to recreate who my father was for Bruce.

The events are very old and my father died a long time ago. There were no MRIs or PETs available. So Bruce’s knowledge of my father could only come from me and the stories I remembered about him before he was sick [and] while he was sick.

Being Patient: It has been difficult for you to recall your memories of Jerry before he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. Why is that?

Cindy Weinstein: What I realized in the course of writing the book was that … I had hid away [memories of my father before he got sick] so deeply and so carefully, because it was too painful to remember him as a healthy person.

“Being able to tell my story of broken

grief and very long grief and deferred grief

is my way of trying to help readers understand that

whatever they’re feeling, it’s okay to feel it. You can’t help it.”

I had 25 years with him as a healthy person. But the disease was so overwhelming that it blocked [my] view [of] all of these really happy, wonderful memories. Writing the book allowed me to grieve for my father in a way that I had been unable to for a very long time … It was only by working out the grief, remembering the extremely painful things and looking at them very straightforwardly that I was able to get to the happy stuff that happened before my father got sick.

Being Patient: Bruce, is it often hard for caregivers and families to remember the memories of their loved ones before a dementia diagnosis?

Bruce Miller: It is. The negatives of caregiving [and the] effects on the health of the caregiver can be so overwhelming that people forget who the person was [and] why they love [the person]. This is very common.

Good clinicians spend a lot of time trying to get a sense of where someone is, but also encouraging them that they are doing an extraordinary job of looking after a very important, special person, and that very important, special person — even though they may have trouble with memory now — is putting out a herculean effort to communicate [and] remember. For me, validation is the first step in helping people think about the good times.

Being Patient: Cindy, you were a graduate student at the University of California Berkeley when you found out that Jerry was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. So you were in a very different place than your parents: While you were having a great time studying at school, far away from your parents, they were going through quite an unhappy period in their lives. How did you contend with this situation?

Cindy Weinstein: How did I do? The harsh English professor critic in me says, ‘Terribly.’ I went into serious compartmentalization mode. By day, I was [a] happy English PhD student, loving Berkeley, reading everything I could get my hands on, becoming the best reader of literature I could be. At night, the lights would go off and I would feel like I had an elephant on my chest.

Anxiety wasn’t such a term then compared to now, but I recognize it as that now. In the book, I talk about having a really dangerous compartmentalization of life. My parents were suffering inordinately. My mother was losing her social world. She was extremely social. My father, less so, but still his friends and his golf partners meant a lot to him … I knew my parents were suffering terribly and feeling abandoned. A part of me thought that I had abandoned them too by staying in Berkeley. Yet, I knew that my parents would never want me to give up on my dreams.

Being Patient: Jerry had early-onset Alzheimer’s with the logopenic variant, which is characterized by the loss of language. Bruce, can you tell us more about this variant of Alzheimer’s from a scientific point of view?

Bruce Miller: The term was first used by a language neurologist, Marilu Gorno Tempini at UCSF. This group of people [with the variant begin having] trouble finding words [and] holding verbal information for very long. Often, one or two words is all that they can understand at once. [The variant is] often associated with trouble reading and writing. This turned out to be one of the major subtypes of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Marilu initially described the clinical features.

Then, as we started to do neuroimaging and ultimately [study] pathology on our patients, we began to learn that this was a type of progressive language disorder that is not the frontotemporal dementia subtype that we had studied. It was unique.

Want to learn more about clinical trials

for Alzheimer’s and dementia?

Check out the Lilly Trial Guide.

As this was studied further by [Zachery] Miller, we realized that many of the people that got this form of Alzheimer’s disease had been dyslexic. In childhood, as many as 50 percent of this population had learning disabilities. It’s made us think in a very different way: When does a disease begin and what makes us vulnerable to one disease versus another?

It’s not that dyslexia causes Alzheimer’s. But if you are dyslexic and get Alzheimer’s disease, it may manifest initially in that vulnerable language circuit that you were brought into the world with.

Being Patient: Cindy, what were the symptoms of Jerry’s loss of language?

Cindy Weinstein: They include a loss of conversation. I would call my parents in Florida. My mom was always the more talkative one, but I was extremely close to my father. Our conversations were mostly me talking and him responding in a monosyllabic fashion. Then, he would turn the phone over to my mother, so that was strange.

In the days of writing letters. my father’s handwriting — it was never very good to begin with — got significantly worse. He would type letters to me on his IBM Selectric. There would be many more spelling errors than in the past, some of which he would catch. There would be an ‘X’ and he would do the correct letter. Sometimes, he didn’t even notice that there were spelling mistakes.

One of the biggest symptoms that I didn’t know was a symptom, but learned from Bruce that it was, had to do with my father’s mood. He was really quite depressed in the early 80s. My family chalked it up to the fact that he was selling his business that he had been in with his brother-in-law for a really long time.

Even though he was excited to be moving back to Florida, it was a huge transition moving from New Jersey to Florida … I remember going back to New Jersey with my boyfriend, now my husband, [and he] said to me, ‘Your father doesn’t seem like the person you told me he was.’ I said, ‘Well, he’s depressed.’

Bruce Miller: Many times, we see, before someone even develops obvious manifestations of a neurodegenerative disease, a mood disorder. We forget that things like mood and anxiety and psychosis all come out of the brain. If a disease hits a part of the brain that is involved with mood, it’s not unexpected to see somebody who is very depressed. [It] doesn’t mean it isn’t treatable, but sometimes, the depression is [present] even before someone is aware of their illness.

Being Patient: So depression can be an early symptom of dementia.

Bruce Miller: Absolutely, and I take very seriously the new onset of a mood or an anxiety disorder or a psychosis in someone over the age of 50, because it’s not uncommon that we eventually learn that they are on the road to a degenerative disease.

Being Patient: Cindy, what works of literature spoke to you the most while you were writing the book and while your father was living with Alzheimer’s?

Cindy Weinstein: The book that makes the biggest appearance throughout Finding the Right Words is Moby Dick, which I first read when I was 16 in high school, and I have never recovered from Moby Dick … It’s a book that has helped take my emotional temperature. I know that I’m doing well when I connect with Ishmael, who is a very funny guy and has a brilliant way with words. [He] gets seduced by Ahab for a little while but then — spoiler alert — manages to survive at the end. When I haven’t been doing so well emotionally, I understand Ahab in a way that is not good, shall we say.

What I’ve also come to realize is The Whale is a very important character. He’s probably the one one wants to be most connected to, because the way [Herman] Melville (Moby Dick’s author) describes him is his eyes are on each side of his face, so he’s able to hold two completely disparate concepts in his brain at one time. That’s what I’ve tried to do in the book: be The Whale.

Being Patient: What do you hope people can take away from the book?

Cindy Weinstein: I hope they can get information that will allow them to be better advocates for themselves and their loved ones when they interact with the medical and scientific community.

The other thing is that I hope people who are experiencing grief can know that — and Helen Macdonald’s H Is for Hawk talks about this — there’s no such thing as normal grief. If it takes 30 years, it takes 30 years, and there’s nothing you can do about that. If you don’t go through the various stages of grief the way the books tell you you’re supposed to, that’s alright.

Being able to tell my story of broken grief and very long grief and deferred grief is my way of trying to help readers understand that whatever they’re feeling, it’s okay to feel it. You can’t help it.

Being Patient: Bruce, do you have any thoughts to add about the book’s takeaways?

Bruce Miller: I hope people [who] read it aren’t scared by the story and are left with a sense of hope that we will do better than the previous generations did and we’ll do better 10 years from now. The therapies are coming and that’s going to be a very different set of stories. What happens when someone returns from deficits or whose deficits suddenly stop progressing? That’s the space we’re in now, so there’s always going to be a need for human stories.

“I emphasize the good things that I can see:

the wonderful humanity of the patient and their

loved one, and the things that they do that bring joy to

them and their grandchildren and others around them.”

Being Patient: Regardless of how advanced medical technologies become, understanding the patient’s story will always be important.

Bruce Miller: What a good physician does is he or she learns people’s stories, listens [and] hears where someone is coming from. Without those personal stories, we’re quite inadequate in our ability to heal.

Being Patient: As a clinician, how do you offer hope for families without offering false hope?

Bruce Miller: Most of these diseases [progress slowly]. I emphasize the good things that I can see: the wonderful humanity of the patient and their loved one, and the things that they do that bring joy to them and their grandchildren and others around them.

I talk about exercise. I really do believe that this slows progression of illnesses and increases well being. [I] emphasize social networks stimulation. [I] emphasize that the average person with Alzheimer’s disease who starts on the type of medication that is helpful is about where they were after a year.

[The disease] is not necessarily going to rob you instantaneously of all cognitive abilities. In the meantime, there are new therapies coming fast, so it is a hopeful time.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Contact Nicholas Chan at nicholas@beingpatient.com