Researchers share insights on the infectious theory of Alzheimer’s—the idea viruses and bacteria may cause Alzheimer’s. Clinical trials are underway to test this theory.

Scientists in the field of Alzheimer’s have long focused on abnormal beta-amyloid proteins as the target for treatments. Given the failures of clinical trials that pursue this approach, scientists have begun expanding their horizons, testing various hypotheses in search for an effective therapy. The infectious theory of Alzheimer’s is one such idea, which posits that the disease can be caused by pathogens such as viruses and bacteria.

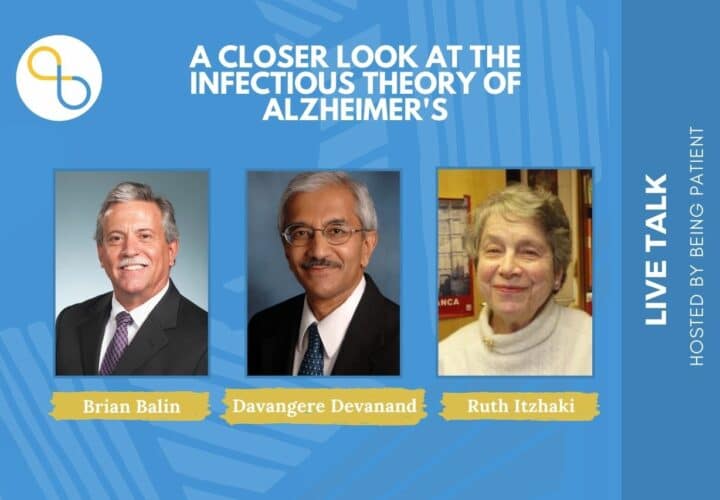

While scientists have viewed the theory with strong skepticism, experts say there has been growing interest among the scientific community in studying the role of pathogens in Alzheimer’s. Being Patient spoke with a panel of researchers about the evidence behind the infectious theory of Alzheimer’s and future research needed to prove the validity of the idea.

Speakers:

- Brian Balin, professor of neuroscience and neuropathology, and director of the Center for Chronic Disorders of Aging at Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine

- Davangere Devanand, professor of clinical psychiatry and neurology at Columbia University and principal investigator of the Valacyclovir Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease trial

- Ruth Itzhaki, visiting professor of the Institute of Population Ageing at University of Oxford and professor emerita at University of Manchester

Being Patient: Why are scientists studying the role of pathogens as a cause of Alzheimer’s?

Brian Balin: This goes back actually to the days of [Alois] Alzheimer and Oskar Fischer when they were first identifying pathology in brains of individuals that had died with severe dementias. It was proposed at the time that potentially an infectious agent could be involved and they thought it was potentially a filamentous type of infectious agent, because they saw all these silver stained large filamentous structures in brain tissues.

That sort of went by the wayside for a long period of time. It wasn’t until the 1980s that [more research in the area was done]. Ruth started a lot of this work with finding herpes simplex virus 1 [being] associated [with Alzheimer’s]. Then more serious investigations started in the late ’80s, early ’90s, mid ’90s and going to current, where we started finding a number of different infectious agents in human brain tissues. These are Alzheimer’s individuals that went to autopsy. We examined the brain tissues and found evidence for these infectious agents. Based on that, we think maybe infection is involved in the pathogenesis of the process or the development of Alzheimer’s disease.

Ruth Itzhaki: We decided to look for a virus in the brain because of two main reasons. Firstly, it had to be a very common virus and herpes virus is very common. The reason why we looked for herpes virus was also because in a very dangerous acute disease (herpes simplex encephalitis), which luckily is very rare, the brain shows in some regions close similarities to the regions in Alzheimer’s disease. It was suggested by the neuropathologist Melvyn Ball.

We started looking for this virus in Alzheimer’s disease brains and elderly normal brains by a technique known as PCR, polymerase chain reaction, which you probably have heard about now, because it’s commonly used to look for SARS-CoV-2 virus. A few people had looked in normal brains for infectious agents. There was some suspicion there might be something there but the techniques they used were very, very insensitive, whereas PCR is extremely sensitive. People are now finding more and more infectious agents. It seems there are a lot of infectious agents in the brain, but probably a lot of them are doing absolutely nothing.

[Another] characteristic of herpes is it can lie dormant in the body for a very long time. One would assume that an agent that causes Alzheimer’s disease, if it would cause Alzheimer’s disease, would have to stay in the body for a long time because the disease is very slow.

Being Patient: What could happen when herpes simplex virus is dormant in the body?

Ruth Itzhaki: The possibility is that inflammation in the brain can reactivate HSV-1, herpes simplex virus type 1. We’ve [done] some experiments which suggest that that is actually happening with at least one infectious agent we’ve looked at. We hope to do several others.

[It could] also [be an] explanation for damage caused by head injury, because it’s known that damage to axons in the brain does reactivate HSV-1. There’s quite a lot of events that causes reactivation. The curious part though is that infection with HSV-1 also causes inflammation, so it’s a vicious circle.

Being Patient: The infectious theory is one hypothesis about the cause of Alzheimer’s. If it is indeed proven to be true, do we agree that Alzheimer’s could be caused by various pathways aside from microbes?

Davangere Devanand: You’re bringing up a very key point that Alzheimer’s disease, in a way, is the end-stage of many problems or insults to the brain. The associations that have been seen with infectious agents like herpes simplex virus, we also see with other conditions such as cerebral vascular disease confounding the clinical picture. As people are living longer, [it] has been found consistently that when somebody is 85, 95, 100 years old and dies with a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s or doesn’t have a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s, it’s very common to have Alzheimer’s disease [pathology], vascular pathology, sometimes Lewy body pathology which is linked to Parkinson’s disease. Multiple neuropathologies exist in the brain by the time one gets into the eighth, ninth, tenth decades of life. The idea that there may be multiple factors leading to multiple pathologies is gaining credence.

I wanted to point out a couple of things in Ruth Itzhaki’s work. In basic science studies, some from her lab and some from others, the herpes simplex virus can be associated with increased amyloid and tau protein formation in animal models. And when antiviral medications [are tested] in animal models and cell culture models, they have effects against amyloid and tau.

In the last few years, there have been epidemiological studies in the community showing an association between prior exposure to herpes simplex infection, to a smaller extent herpes zoster infection which is what causes shingles, and Alzheimer’s disease. There were a couple of studies out of Taiwan which showed a very robust effect of antiviral medication treatment in reducing the risk of Alzheimer’s. Those findings have been replicated, but with a much smaller effect size, meaning the reduction in risk from the antiviral drugs is not as robust, but it is still there. These are studies coming mainly out of Europe, and one out of South Korea.

We have a lot of converging lines of evidence. The one thing we don’t have yet, which is what I’m trying to do funded by the National Institute on Aging, is a prospective clinical trial comparing [the] antiviral medication valacyclovir to placebo to show that there’s a clear difference.

Being Patient: Pathogens aside from herpes simplex virus have been implicated in Alzheimer’s. Brian, can you share with us your team’s research into the link between Chlamydia pneumoniae and Alzheimer’s?

Brian Balin: When we first got into this particular field of study, I was looking at the atherosclerosis literature. This is blood vessel disease and Chlamydia pneumoniae was proposed to be involved with that going back to the early to mid 1990s. In a discussion with a colleague of mine Dr. Alan Hudson, we thought why don’t we try looking in brain tissues because of this organism’s involvement in blood and see if we find anything in diseased brains or normal brains, etc. In his lab, he did a lot of PCRing, looking for a genetic signature of this infectious agent in brain tissues, finding it in Alzheimer’s disease [brains] and not in age-matched control brains. We started publishing in 1998 to current.

This organism is an intracellular bacteria, meaning it acts like a virus by invading ourselves and starts to live and set up shop in ourselves and can become persistent. In that way, it’s very similar to what would happen with herpes. You’d have an infection that could persist for a long period of time in our tissues, particularly in our brain.

After many studies, we’ve realized that this organism as a respiratory pathogen can actually get into the brain through our olfactory system, but also go into the brain through the blood by infecting white blood cells from lung tissues. You have two mechanisms that this organism can actually invade the brain. We actually are of the belief that [the organism can invade] the olfactory pathway first, partly because Alzheimer’s disease starts in the entorhinal cortex, a part of the brain that is connected to olfaction. We think the entorhinal cortex is key. From the entorhinal cortex, you have connections going into the hippocampus.

What do you find in the disease symptomatology? You find [a] change in sense of smell early, and also short-term memory is affected. We think that you’re setting the stage here with this type of infection, generating inflammation, glial responses, generating amyloid.

Some of our studies have shown that you infect cells in culture and you will produce amyloid. Just about every cell we’ve infected – a monocyte to a neuroblastoma cell, glial cells, endothelial cells – process amyloid that’s in their membrane into Abeta, or beta-amyloid, in particular the 1-42 form which is the most commonly found form in amyloid plaques.

There was a recent study out from Taiwan showing that people that were diagnosed with Chlamydia pneumoniae pneumonia had a 1.6-fold increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. Over 1,000 patients were looked at compared to almost 5,000 controls.

Want to learn more about clinical trials

for Alzheimer’s and dementia?

Check out the Lilly Trial Guide.

There is a story here where we think that these organisms — the herpes, the Chlamydia, maybe Borrelia, maybe some of the oral organisms — can actually begin the change in the brain that would eventually lead to what we’re calling Alzheimer’s disease.

We need to do clinical trials on a lot of these effects of different organisms with individuals that either have a risk because they have been infected and are older individuals or that show mild cognitive impairment, especially amnestic mild cognitive impairment, or very early Alzheimer’s disease.

This also goes to the point I wanted to make about multiple infections in Alzheimer’s disease. If we use the analogy that Alzheimer’s disease is really like what we call pneumonia, pneumonia can be caused by viruses, bacteria, fungi, aspiration issues like food particles getting into your lungs. You have multiple ways you can get to the end point we call pneumonia. We think there’s multiple ways you can get to the end point we’re calling Alzheimer’s disease.

Being Patient: One of our viewers noted that tuberculosis (TB) meningitis is an example of a treatable intracellular brain infection and asked whether it’s possible that like TB, we need to give multiple antibiotics for an extended amount of time to achieve high enough brain concentrations to eradicate organisms like Chlamydia and Borrelia?

Brian Balin: Yes, it’s quite possible. It wouldn’t be one antibiotic that would be used in that approach. [It would] potentially [involve using] two to three different antibiotics. Also, by doing that, you’re minimizing the risk that you’re going to have some type of resistant mechanism from the organism.

Being Patient: The viewer also asked whether the variety of microbes with the capability to impact the brain directly or indirectly would call for a more precise approach to analyzing and treating patients?

Davangere Devanand: Diagnostically, we are looking for specific infectious agents, for example herpes simplex virus. Slightly more than half the population has had HSV-1, but then a large minority has not. One argument against the infectious hypothesis is there are plenty of people who get Alzheimer’s and you test them for antibodies and they never got herpes simplex [virus]. That comes back to Brian’s point that there are multiple ways you may get Alzheimer’s, or you have multiple factors contributing to different degrees.

Translating from a theoretical concept [of treating] multiple possible infections [and diagnosing] everybody in great detail is difficult to do practically because we will need to do a large number of diagnostic tests to cover the whole range of possible infections a person has.

While we’ve talked about giving multiple antibiotics and antiviral drugs, it’s important to recognize that when you start giving high doses for long periods of time, you have to be careful. There are clinical side effects and it’s not so simple. Translating from a theoretical construct to clinical use is hard and that’s why the intermediary is clinical trials to make absolutely sure that you really need to do that.

Being Patient: Can you give us an idea of the ongoing clinical trials that are testing the infectious theory of Alzheimer’s?

Davangere Devanand: There are many associations with pathogenic agents like viruses and bacteria, environmental problems like air pollution, even physiological factors like diet, exercise, cardiac disease. They’ve all been associated with increased risk for Alzheimer’s. When one tries to do clinical trials, it may or may not work. One great example [is] people who took anti-inflammatory agents like ibuprofen, naproxen, [and] other anti-inflammatory drugs for various conditions. Most of the studies showed [they] prevented Alzheimer’s, but when clinical trials were done, they failed. The clinical trial, at least for now, is a gold standard.

For the viral hypothesis, I’m doing a couple of trials, one with valacyclovir versus placebo in mild to moderate Alzheimer’s. We will finish recruitment in the next few months. I got funded by the Alzheimer’s Association for a smaller study to look at people with mild cognitive impairment, which is generally a stage between normal and Alzheimer’s. Not everybody with mild cognitive impairment is going to get Alzheimer’s, so in that study, we also require amyloid positivity on PET imaging. There is a small study done in Sweden by Hugo Lövheim’s group that’s an open study looking at when you give valacyclovir, what happens to the brain and peripheral biomarkers?

One of the reasons all these trials are going on now is that 10, 15 years ago, every grant that was submitted with a viral hypothesis and clinical trial ran into roadblocks. Ruth and Brian are smiling. They’ve been through that. I myself went through that several times.

In the last five to 10 years, because of increased funding for Alzheimer’s, there has been a realization we need to be broad in looking at possible therapeutic agents. The main Alzheimer’s field was not really interested in [the infectious theory of Alzheimer’s], but now they are. Before going to a huge clinical trial, there has to be some signal from smaller studies before one gets that level of funding. In a couple of years, we would have enough information to know whether this makes sense as a clinical intervention or not.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Contact Nicholas Chan at nicholas@beingpatient.com