Dr. Jacob Dubroff discusses the role of PET scans in detecting patterns of brain activity tied to dementia and other neurological conditions.

This Live Talk is produced by Being Patient with support provided by the Society of Nuclear Medicine & Molecular Imaging and Eli Lilly and Company.

The Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging will hold its 2025 Patient Education Day on June 22, available both in person in New Orleans and livestreamed via YouTube. The event will explore the role of nuclear medicine in diagnosing, managing, and treating disease, with a special focus on Alzheimer’s disease, prostate cancer, and neuroendocrine tumors. Dubroff will be speaking at the Alzheimer’s breakout session during the event.

With the approval of new Alzheimer’s therapies that target amyloid plaques in the brain, PET scans are playing a larger role in the diagnostic process. These imaging tools are helping doctors determine whether a patient has the specific biological markers that qualify them for treatment, bringing new visibility to molecular imaging in dementia care.

Dr. Jacob Dubroff, MD, PhD, an associate professor of radiology at the University of Pennsylvania, specializes in molecular imaging techniques such as PET and SPECT scans to detect patterns of brain activity tied to dementia, addiction, and other neurological conditions. He plays a pivotal role in interpreting scans to help clinicians distinguish between different types of neurodegenerative disease, including Alzheimer’s, frontotemporal dementia, and Lewy body dementia.

In this conversation with Being Patient founder Deborah Kan, Dubroff explains why PET scans are not all created equal, how radiotracers target amyloid and tau proteins, and what imaging can and can’t tell us about cognitive decline. He also discusses why MRI remains the first step in the diagnostic process, the promise and limits of blood tests, and how changes in insurance coverage are shaping access to brain imaging in the era of anti-amyloid treatments.

Being Patient: What is a PET scan?

Dr. Jacob Dubroff: PET stands for positron emission tomography. For a long time there, we had very few choices in terms of what types of radiotracers our positron emission tomography instrument could see. So positron emission tomography is basically a very fancy radiation detector where we can look at the distribution of very small positrons, [which] give off even smaller photons inside of a person, and give us a map of different processes.

Being Patient: What a lot of people understand is you drink a dye, or you have a dye injected into you, in order to see all of this. Tell us a little bit about that. What is it picking up on? And why do you have to have a dye injected?

Dubroff: So the dye is a very small amount of radiation, which our machines are very good at detecting, and they’ve been developed for the past almost five decades. The most used one, and most often associated with PET, is fluorodeoxyglucose, which [chemically] very closely looks like a glucose molecule. We’re essentially making a map of sugar, and how your body is using sugar.

Now, although we’re talking about the brain, a lot of my practice and a lot of the development that has occurred has been largely oncology, because many different types of cancer really like to use glucose, and so we can say where the cancer is or if it’s responding to a therapy.

In the last 15 years, we’ve accelerated our ability to use other types of dyes to look for other problems or other processes in the body, including a lot of the abnormal processes that occur with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

“In the last 15 years, we’ve accelerated our ability to use other types of dyes to look for other problems or other processes in the body, including a lot of the abnormal processes that occur with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.”

Being Patient: PET scans are the gold standard to diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease. A lot of patients, when they first go in for early diagnostics, are given MRIs. Why is an MRI being given and not a PET scan if we’re so sure PET scans are the gold standard of diagnostics?

Dubroff: MRIs show us a distribution of water molecules or soft tissue molecules. Before you start evaluating for neurodegenerative disease, MRI is usually cheaper, easier to get to, and doesn’t have any radiation. The way a lot of our insurance structure is set up is we don’t want to do a PET scan until we had an MRI that did not demonstrate a straightforward reason why someone may be having a neurocognitive issue.

Being Patient: Is it possible to diagnose Alzheimer’s with MRI, looking at brain atrophy? Is there a pattern of atrophy that would indicate that there is dementia?

Dubroff: There is a specific pattern, and neuroradiologists are exceptional at detecting that pattern. Largely, those are based on changes in how particular places, including your temporal lobes and your hippocampi, may atrophy, may decrease because the cells are dying. However, volume changes [picked] up with MRI, we’re not able to detect those so reliably in the early stages of the disease. The way you really make a modification for dementia or cancer is to get the disease as early in the process as possible, before you do the intervention.

Being Patient: Before, most people wouldn’t be able to get a PET scan because they couldn’t afford it, because it wasn’t covered by insurance. That landscape is now changing with the FDA approval of monoclonal antibodies. Give us insight into what it means to have more people with cognitive symptoms getting PET scans. How is that going to change things?

Dubroff: My role is looking at these scans and interpreting them, being consistent and quantifying them, and developing them. But before someone undergoes a PET scan we really want [them] evaluated by a memory specialist, a behavioral specialist, to decide: Do they need a PET scan? Which type of PET scan, based on their symptoms, age or history, would be the most appropriate?

Once we get that, I’m going to look at that data very carefully to say, what are the symptoms here — why are they doing a PET scan? Sometimes I will call the physician and say, I don’t think this is the right indication. Maybe this person wasn’t being seen by a neurologist. Is this the right test? We really want to quantify what’s going on with behavior. We want to make sure the right person is evaluating the patient and then ordering the right test.

Then it ends up in my hands, and I’m trying to make the right diagnosis with the right PET scan. Unlike 10 years ago, now we have other flavors of PET scan — not just glucose. We can look for amyloid, which we think is the first abnormal protein to accumulate in Alzheimer’s. There’s kind of a cascade of things that happen. We think amyloid is the first, and maybe the tau protein is the second, and further down, as [we] talked about with MRI, that happens more toward the end, after a lot of these problems are very fulminant.

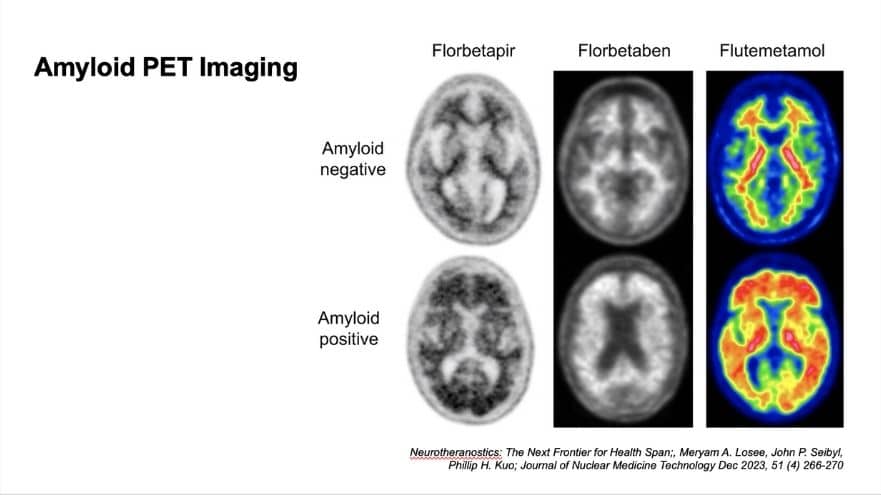

Being Patient: I’m sharing some images that you have prepared for us. Talk us through what we’re seeing here, and what does this actually mean from the patient’s perspective?

Dubroff: So these are PET scans of the head, cross-sectional, so eyes through ears at this level, and showing us part of the brain. Now, the top row is negative scans, and the bottom row is positive scans. The three columns are the three FDA-approved types of radiotracers that we can inject into a patient to determine if there is amyloid plaque there.

Being Patient: Would you be injecting people with all three of these? Or would you pick one?

Dubroff: You just get one. There is no data comparing one to another. As far as I’m aware, there’s not one that I think is superior, that you should get versus another.

Being Patient: What are we seeing in the imaging? How much plaque is this in the brain? Is this early, mid, late stage? What are we seeing?

Dubroff: The scans on the bottom are all very positive. We usually don’t get such positive scans, but there is no direct relationship between the amount of amyloid and the amount of cognitive deficit between patients.

Being Patient: So the amount of plaque you have is not directly linked to cognitive decline?

Dubroff: How much plaque you have is not correlated with how severe your deficits are. We will look at a scan and want to say, is there plaque? Is there not?

What we see on the top, the tracers in the negative scan cling to what we call the white matter, where there aren’t neurons that are doing the work. They’re carrying signals back and forth between different places in your brain. On the bottom, you get a blurring of your gray matter with your white matter. You can’t tell where one starts and one ends, because there’s a lot of plaque in there. What I’m looking for when I’m reading a less positive scan, but a data-positive scan, is a blurring in one or more regions of the white-to-gray transition — seeing if there is abnormal protein, abnormal tracer binding in that gray matter. And that is allowing me to say, ‘Hey, this is a positive scan.’

“How much plaque you have is not correlated with how severe your deficits are. We will look at a scan and want to say, is there plaque? Is there not?”

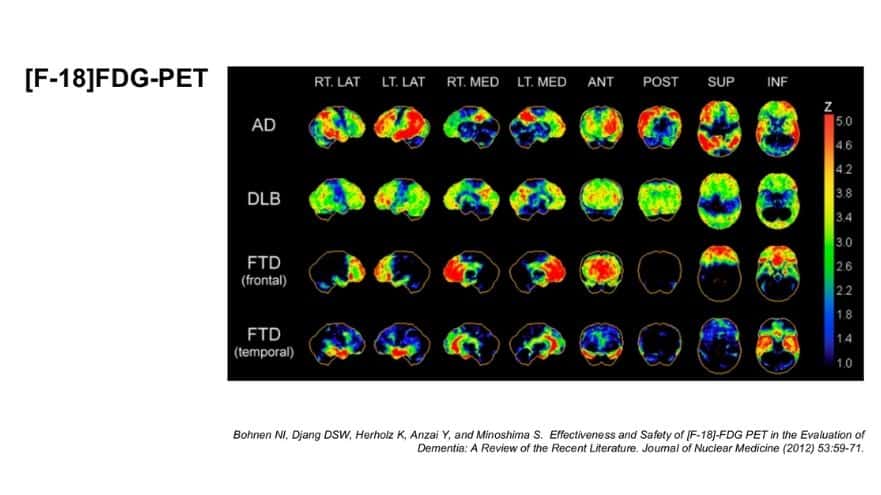

Being Patient: Can you explain what we see in this picture?

Dubroff: What we have here is the four rows — the AD, DLB, FTD frontal and the FTD temporal — [these] are different types of dementia. These are three-dimensional maps. The more intense the color toward red, in that z bar on the right side, the greater the deficits in glucose metabolism.

If you look at that third row down, the FTD — frontotemporal dementia — you see that frontal part of the brain has a lot of red in it, but most [of] the rest of the brain is spared, because it’s the frontal part of the brain that isn’t metabolizing glucose, and where the cells are probably dying, because that’s that type of dementia.

Being Patient: So the red indicates you know that there’s a problem. When you just look at the comparison between Alzheimer’s and FTD in the frontal region, it’s very clear, right? Alzheimer’s seems to kind of present in different parts. I always thought you see it in the hippocampus, but maybe I’m wrong, so talk to me a little bit about that?

Dubroff: Where we see the deficits in glucose in parts of the brain doesn’t mean there’s abnormal amyloid accumulating in those same [people]. That is the pattern that the neurons are not using glucose. For example, if you’re not using certain parts of your brain, you may have language deficits, or you may have [an] inability to do math or keep your checkbooks or be spatially aware. Those can be more in the parietal lobe. That’s where we often see those deficits.

These are maps generated representing multiple patients. There’s much more nuance in interpreting an individual study where, especially now, doctors are more likely to have heard of a PET scan and order them earlier in [the] disease. We are trying to pick up more subtle changes that could suggest something so we can get that diagnosis as early as possible. And that can be really tricky sometimes.

Being Patient: Are these pretty clear-cut? Would scans like these say, this person definitely has Lewy body, this person definitely has frontotemporal lobe, or is there something else they have to actually do to confirm this?

Dubroff: These are patterns of how the neurons are dying or not using glucose. They are associated with different dementias, but they’re not the same as the amyloid and the tau scans, because those are actually showing the abnormal protein.

In my experience as a practitioner, I have had some very atypical [scans showing] abnormality on the glucose image, but the test doesn’t make sense relative to what the patient is presenting with, or a different type of disease process is going on. For example, I remember we had at our institution a very interesting case where their FDG PET scan looked very much like an Alzheimer’s patient, but it was a younger patient, and it was actually a very rare disease called Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, a prion disease (which comprises a group of rare, fatal neurodegenerative disorders). It was not Alzheimer’s, but [from the test], that’s what it looked like. But it was just a pattern of how these cells were no longer behaving properly.

Being Patient: If we can see Alzheimer’s on a PET scan, why can’t we see CTE using a PET scan?

Dubroff: Because there’s not one exact problem that occurs in CTE consistently. Traumatic brain injury is a more heterogeneous disease in terms of the types of insults and how many insults you have. A lot of the literature [comes] from the professional football players, but then there’s also different literature from our veterans, and there are different patterns that have emerged.

There hasn’t been the same kind of efforts to describe that disease using these markers. We haven’t put the full effort of our focus in medical science using PET. It’s a little bit more straightforward [to analyze] how Alzheimer’s disease develops. CTE is a little bit more of a different beast.

Being Patient: Looking at this next slide, are you using the same tracers for tau that you are for amyloid?

Dubroff: No, it’s different. It has to be a different tracer because it has to actually bind differently. This is flortaucipir — this is the only one that’s currently FDA-approved.

We’re trying to understand the relationship between amyloid and tau, and wondering if patients who likely have Alzheimer’s have a little bit of tau or a lot of tau. That helps us stratify who gets what treatment, or what type of treatments they can have, or if they’re not a good candidate for treatment. It’s really helping us understand the disease process and how to treat the patients best.

“We’re trying to understand the relationship between amyloid and tau, and wondering if patients who likely have Alzheimer’s have a little bit of tau or a lot of tau.”

Being Patient: Does a positive PET scan automatically mean Alzheimer’s is present?

Dubroff: As I explained, for the fluorodeoxyglucose, we can have false positives. That’s why we want these clinical dementia experts to order the test. You can have false positives for amyloids, and it should not be used as a screening test.

I would say the same thing for someone who clinically might have Lewy body dementia. The data there has shown us that about half the patients have a positive amyloid and half don’t. So it doesn’t give us better insight into whether or not that patient actually has Lewy body dementia. Again, we want to use the right tool in the right scenario, and we continue to work out these different permutations. So a PET is not a PET — there’s different types, for different situations.

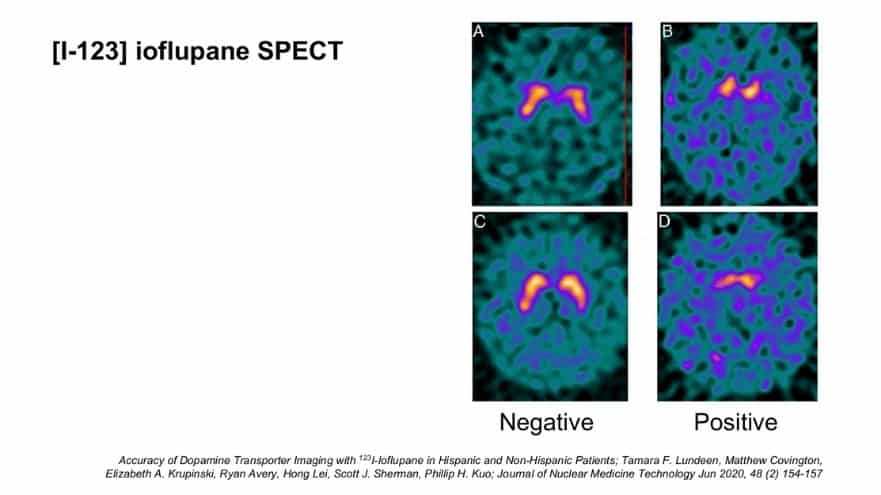

Being Patient: Tell us about a SPECT.

Dubroff: This is a test that was FDA-approved in 2012 in the U.S., and has been available in Europe for about the better part of two decades, if not more. This is also nuclear medicine, but it’s not PET. SPECT is single photon emission computed tomography. It works very similarly, in that you get an injection of a radioactive tracer, and then this tracer takes about three hours to distribute, and then we take an image of your head.

What we are looking for here is [the] portion of the brain that uses dopamine — specifically, presynaptic dopamine receptors. This gives us a way of saying: How much dopamine cell mass do you have? Do you have a normal amount? Or do you have an abnormal amount? This test was first developed to be used for Parkinson’s disease.

Being Patient: What does it mean for diagnostics to have blood tests, plus PET? Is it more accurate?

Dubroff: The blood test [was just FDA-approved] a week and a half ago, two weeks ago. PET scans are still expensive, and they’re still radiation. You have to schedule an appointment. We don’t use them as screening tests. On the other side, a blood test is not an indication to have the anti-amyloid therapy, at least at this point. One of the things that has to be worked out is the relationship between these blood tests and the imaging test to see what to do, when, [and] in which situation.

I think what we’re going to have to figure out is, maybe the blood test is a good way to start screening, and if we see something, we want to do the amyloid test. With therapy, there are risks. We want to stop if we’ve cleared the amyloid. Understanding the relationship between the blood test, having an eye toward what economically is feasible and sustainable between the two, and how we can use the two to monitor therapy together — these have not been worked out.

I’m all for using all the information we can have in the most patient-focused way to figure out what’s a screening tool [and] what’s not. When can we substitute one for the other one? When can we not? They’re safe and they’re great, but we don’t know how they relate exactly to one another at this point.

“One of the things that has to be worked out is the relationship between these blood tests and the imaging test to see what to do, when, [and] in which situation.”

Being Patient: Are you seeing changes in volume of PET scans coming in due to the monoclonal antibody therapies being approved by the FDA? Are you seeing that maybe some people who were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s actually don’t have amyloid?

Dubroff: There’s a lot of interesting trends. [The] first thing we’ve observed in our institution is that FDG has been used more and more. [We thought] maybe PET amyloid would cause a decrease in the FDG use, but actually, we’re seeing more and more of the FDG use. It’s a tool that really allows patients to be diagnosed properly.

With amyloid, what happens then? There are a number of cases where we have negative amyloid studies. This is just anecdotal, not scientific, but initially, a lot of people wanted to have that test, and I think about 50 percent were negative. We’ll see how the data plays out. But again, if we take a test that may cost a couple thousand dollars, and that may exclude a therapy that costs tens of thousands of dollars over time and has risks, that’s great.