Early-onset Alzheimer’s disease — sometimes called young-onset — can be diagnosed as early as age 30. University of Reading Associate Professor in Cellular Neuroscience Mark Dallas takes a look at its symptoms and causes. Want to hear a patient's perspective? Scroll down for a Q&A.

Alzheimer’s disease is often thought of as a condition that only affects the elderly. But around 3.9 million people worldwide aged 30 to 64 live with young-onset Alzheimer’s disease, also sometimes called early-onset or younger-onset Alzheimer’s – a form of dementia in which symptoms appear before the age of 65. English journalist and broadcaster Fiona Phillips, 62, recently revealed that she’d been diagnosed with it. In the interview, Phillips shared that the main symptoms she had experienced before her diagnosis were brain fog and anxiety – highlighting just how different young-onset can be from late-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

What’s the difference between early-onset and later-onset Alzheimer’s?

First, symptoms begin much earlier – as young as 30 in some rare cases, though it’s typically diagnosed between the ages of 50 to 64.

And, while people with Alzheimer’s disease commonly experience memory loss as the first sign of the disease, people with young-onset Alzheimer’s tend to have other symptoms – such as worse attention, less ability to mimic hand gestures and worse spatial awareness.

Some people with young-onset Alzheimer’s may also experience an increase in anxiety prior to their diagnosis. This may be due to an awareness of the changes occurring, without a clear reason as to why they’re feeling different.

They may think these changes in behavior are temporary, which can put people off seeking medical help. Healthcare professionals may also misinterpret anxiety as a sign of other health conditions.

But while they may have less cognitive impairment at the time of diagnosis, studies have indicated that those living with young-onset Alzheimer’s disease show more rapid changes in their brain. This indicates that the condition can be more aggressive than late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. This may also explain why people with early-onset Alzheimer’s tend to have a life expectancy around two years shorter than those with late-onset.

Research shows that people with young-onset Alzheimer’s are also more aware of the changes in their brain activity. This can lead to behavioral changes – with conditions such as depression being prevalent in this group.

Within the brain itself, young-onset Alzheimer’s disease causes similar chemical changes as those in late-onset Alzheimer’s. But the brain areas targeted by these chemical changes can be different.

Research has found that brain areas involved in processing sensory- and movement-related information (called the parietal cortex) show greater signs of damage. There is also less damage to the hippocampus compared to late-onset Alzheimer’s – an area of the brain important in learning and memory.

What causes early-onset Alzheimer’s?

The risk factors for young-onset Alzheimer’s disease are similar to those for late-onset Alzheimer’s. For example, poor levels of cardiovascular fitness and lower cognitive ability in early adulthood have been linked to an eight-fold increased risk of developing young-onset Alzheimer’s. However, we are yet to fully understand all the factors that influence a person’s chances of developing the condition.

One aspect experts are clear on is that genetics play a role in about one in ten cases of young-onset Alzheimer’s disease. So far, three genes (APP, PSEN1 and PSEN2) have been linked to young onset Alzheimer’s disease.

These genes are all related to a toxic protein that is thought to contribute to Alzheimer’s disease (known as amyloid beta). When these genes become faulty, there’s an accumulation of toxic amyloid beta, which is linked to symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease.

Growing evidence suggests there may also be a link between traumatic brain injury and young-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

Is there a cure for early-onset Alzheimer’s?

In the UK, people diagnosed with young-onset Alzheimer’s disease can be prescribed medication which can help manage symptoms. But in the U.S., two therapies have been approved which may slow the progression of symptoms. However, these were only tested on people with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease, so it’s uncertain if they will have as distinct of an effect.

People who may have a family history of dementia or are concerned about their risk can have a genetic test done through a private company. This will confirm the presence of the faulty genes. These tests can be carried out for those showing symptoms, or those with a family history that wish to know their future prognosis.

While it’s not possible to modify genetics if you are at greater risk, some research does support the idea that you can strengthen your resilience against the disease through a healthier lifestyle. One study found that when people who were genetically predisposed to early onset Alzheimer’s exercised for more than two-and-a-half hours per week, they scored better in memory tests than those who weren’t as physically active.

Alongside being more active, diet choices may also lower risk of young-onset Alzheimer’s. An Italian study found that people who consumed high levels of vegetables, dry fruits and chocolate appeared to have lower risk.![]()

The above scientist’s article by Associate Professor in Cellular Neuroscience at the University of Reading Mark Dallas is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

What are the symptoms of early-onset Alzheimer’s?

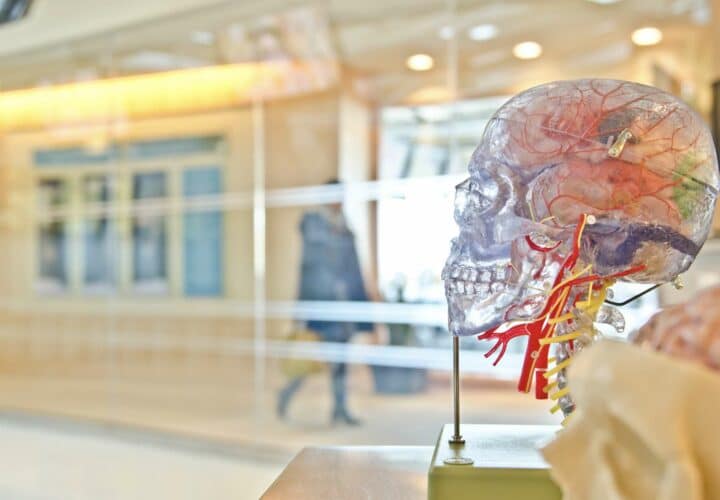

Alzheimer’s disease — including early-onset — affects the brain, especially in areas that involve memory, behavior and language. A healthy brain can send messages through neuron cells to keep the body functioning and Alzheimer’s interrupts those pathways. Alzheimer’s eventually leads to dementia.

Early-onset Alzheimer’s is known for causing dementia, but there are a range of other cognitive symptoms that may come with it as well. These typically begin to occur around the age of 60, though symptoms can be present in people as young as their 30s. The most noticeable symptoms of early-onset Alzheimer’s are:

- Forgetfulness

- Lapses in memory

- Low attention span

- Impaired language

- Changes in personality

- Mood swings

Since Alzheimer’s is generally associated with older adults, it can be difficult for a person facing early-onset to get an accurate diagnosis. Experts recommend that people between age 30 and 65 experiencing problems with memory or the symptoms listed above see a doctor that specializes in Alzheimer’s.

There is currently no cure for early-onset Alzheimer’s dementia. However, the earlier someone is diagnosed, the better chance that they may be able to to participate in clinical trials for experimental treatments, or that existing symptomatic treatments will be effective. Research shows they may also have a more positive response to medications currently used to treat symptoms like memory loss.

Does early-onset Alzheimer’s progress at a faster pace than Alzheimer’s that appears later in life?

In some peer-reviewed and published clinical studies, early-onset Alzheimer’s is has been observed to have a more rapid course compared to late-onset Alzheimer’s, and this is the general understanding — that Alzheimer’s does in fact move faster in younger study participants. However, other clinical studies haven’t found any statistically significant increase among study participants in the course of progression as compared to later onset Alzheimer’s.

The question is also complicated by the fact that familial or genetic Alzheimer’s and non-genetic or common Alzheimer’s may have different pathological characteristics, but researchers are still getting to the bottom of these differences. Learn more here.

***

Young-onset FAQs: A Q&A with patient Laurie Scherrer about her early-onset dementia diagnosis

Want to hear more from the patient’s perspective? Writer, advocate, and international speaker Laurie Scherrer talks early signs of early-onset Alzheimer’s and FTD, learning new things, powering past the bad days, and writing her way through it all in her blog, ‘Dementia Daze.’ Read part of our conversation with her below.

Being Patient: What were some of the early signs of Alzheimer’s you were experiencing?

Laurie Scherrer: I was a career with a lot of community activity and involvement, plenty of social activity, and an abundance of family activity, and lots started to change. I think I first noticed it when I was having trouble with just basic math. Even when using Excel or a calculator, my fingers were constantly wrong. At times, I would get lost driving in places that I knew so well. Then I started forgetting entire conversations. I mean, not a two-minute conversation, a long conversation, and I totally didn’t remember them.

Then I started having problems thinking through the processes that were normally second nature to me. Although I’ve always been a very positive motivator, I became increasingly agitated by people, events, and things that normally, you know, you could just brush off your shoulder and go, “What the heck?” I couldn’t anymore, and I couldn’t understand what was happening to me or why I was having such a personality change in general.

Being Patient: You were in your early 50s at your time of diagnosis. Tell us a little bit about what was going on at work and how the symptoms really started to present.

Scherrer: I’ve had a fun and wonderful career. I was in banking for 18 years and was the vice president of a bank. I ran their customer sales and service center. I then decided I wanted to get into sales because I really enjoy that as opposed to managing people. I found sales was a passion for me. I really excelled at sales and made more money than I did as vice president of a bank, to tell you the truth. So as a salesperson, you know, when getting into higher-end sales, you know, so I enjoyed that I enjoyed my career.

“I think that’s what so many

of us do. We just find ways to hide it.”

And then, even driving to work, it was a two-hour drive, which never bothered me before, it just stressed me out to the point I would come home crying. I’d get lost on my way home, and I started finding ways to cover up, cover up for the mistakes I was making, ways to cover up for being lost. I think that’s what so many of us do. We just find ways to hide it.

Being Patient: Could you tell us more about your reaction to the diagnosis? It must have been a shock thinking it was a brain tumor and getting a mixed dementia diagnosis.

Scherrer: We left the doctor’s office and went and sat in the car. We sat in the car and just cried for an hour. It was devastating. It was really hard. You go through periods of grief and total grief for what you’re losing or what you’ve lost, the fear of not recognizing your family. It killed me. I just couldn’t handle that. And you just go through a lot of different stages.

One day I looked at myself, and I said you’ve never lived this way, and you’re not going to, and I just decided to start living my life the best I could every single day. I made a declaration to myself and God that that’s what I was going to do: make the best of every day as long as I could, no matter what.

Being Patient: How long has it been since your diagnosis?

Scherrer: In October, it will be 10 years. I actually have some friends that have lived with dementia for over 20 years, one person is close to 30 and still has a purpose-filled life. Living with dementia doesn’t define me. I’m a writer, I’m a scuba diver. I’m a wife. That’s part of who I am. Yes, I also have dementia, but I’m many other things as well.

Living with dementia, to me, is making the best of every day, enjoying the moment, and learning strategies. When your dementia symptoms are bad, yeah, it hurts, and it’s aggravating, but it’s learning strategies to help lessen them and learning ways to make your days good in spite of it.

Being Patient: When I first started Being a Patient, I was told that people with dementia don’t learn new things. But that’s not true. There are so many people out there with a dementia diagnosis who are learning new things. I want you to talk a little bit about that. Do you feel like you have the ability to learn a lot of new things?

Scherrer: I don’t learn new things as much as I used to, but I can learn new things. Sometimes my problem is not learning new things, it’s remembering the things I did know, like counting money. I can’t count money. It makes no sense to me. Yet, I can learn some new things that use a different part of my brain maybe. I can find strategies to get around things that I used to be able to do that I can’t do anymore. But we do learn things. I have a friend who went on to get his master’s degree after his dementia.

“I’m a writer, I’m a scuba diver. I’m a wife. That’s part of who I am. Yes, I also have dementia, but I’m many other things as well.”

Is it hard? Yeah, it’s really hard. When I can’t read a book anymore, because I forget what I did on the page before. So when I’m reading something that kind of looks like this. It’s all highlights and notes because that’s the only way I remember things. But you can learn new things, you just have to learn them differently, which is the way much of my life is. I still can do many things. I just have to do them differently than I did before.

For more patient perspectives on young-onset dementia, check out these excerpts from Being Patient’s Live Talks series:

Brian Van Buren: Turning an Alzheimer’s Diagnosis into Purpose

This Globetrotting Couple Is Navigating Alzheimer’s—While Running Marathons Around the World

My husband died in May 2023 after having early onset Alz. for 19 yrs. He was only 73 when he died and did not have a lot of the typical symptoms of early onset. My advice is if you can get long term care insurance or start saving your $$ in case you need to deal with Alzheimer’s. It can be a very expensive disease.

Anne, we are sorry for your loss. Thanks for reading and for being here — and thank you especially for sharing this excellent advice! This is a great point, and so many families struggle with this reality. If you’re ever interested in writing something a bit longer about your experience and what you learned, consider contributing to our VOICES section (https://www.beingpatient.com/being-patient-voices/). Submission guidelines are here.