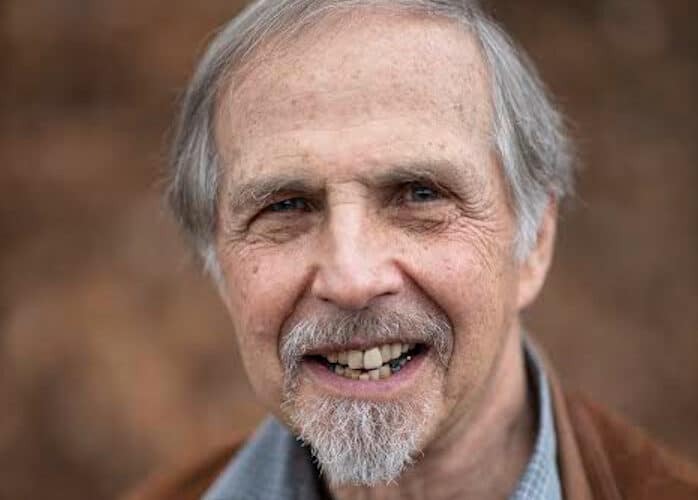

An accomplished physician and professor of psychiatry and medical anthropology at Harvard Medical School, Dr. Arthur Kleinman’s view on the profession was upended when his wife Joan was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s, later writing a book on his experience entitled “The Soul of Care: The Moral Education of a Husband and a Doctor.”

- Joan was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s at age 59

- Dr. Kleinman provided care for his wife for over a decade before moving her to a nursing home

Being Patient spoke with Dr. Arthur Kleinman about his wife’s diagnosis, his perspective on the caregiver experience through the eyes of a physician and his discovery of his own limitations in providing care for his wife.

The Perspective of a Physician Turned Caregiver

Being Patient: You are a professor of psychiatry and of medical anthropology at Harvard Medical School, so completely qualified to speak from a physician’s point of view, but I love that you’ve personalized caregiving from both perspectives. Can you tell us first why that was so important to really write about your own personal experience with Joan?

Dr. Kleinman: The reason I wanted to write about it is that the personal experience of being a family caregiver altered my understanding of what caregiving was about, which came as a shock to me. I had spent five decades of my life studying care, in research, and doing care as a practicing psychiatrist, so it was a surprise to me all the things I learned simply by being a family caregiver. The veil of ignorance was taken off my eyes.

I think the reason for that is that physicians and nurses structure the caregiving experience in terms of their relationship to patients and families. What they leave out is all the time that families are taking care of somebody, in which the world of the patient and the family are radically different from the world in a clinic or hospital. And that family setting, and more broadly that friendship setting as well, is very different.

It’s not just that it’s a home, but it has with it all the relationships that define our life. Our love relationships, our spouses, parents, children. Our friendship relationships, neighbors, the community members. And all the other relationships that define what you do in your life. That’s the way we live our lives. But when someone has Alzheimer’s disease or another kind of dementia, that changes all those things, not just for the person who’s affected, but for the family caregiver as well.

The Caregiving Journey

Being Patient: So obviously you’ve had a lot of medical training and have a long list of credentials, but it sounds like you weren’t prepared for this at all from a physician’s point of view.

Dr. Kleinman: I wasn’t prepared from the point of view of a husband. I’m 78 years of age, this all started when my wife was 59, I was about 58, and went on for a decade. I was totally unprepared. I came out of your classical American, or for that matter East-Asian, family setting, in which my wife practically took care of everything in our lives, and I made the money and did the work.

We were also collaborators in our research, which made us a little different. But my wife was astonishing in what she did, and in the first year when she could no longer do these things, she said, “If I knew how competent you were at doing these things, I never would have let you off the hook earlier on.” But I was totally unprepared.

Being Patient: When she was first diagnosed in her late fifties, did you have the opportunity to discuss with her at all what the later stages of this disease might look like caring for her? And did she have any opinions or input?

Dr. Kleinman: She was ridden with guilt that what should have been our golden years were now going to be something different, and that I would have to bear the burden. My wife was an Audrey Hepburn look-alike, with a fantastic personality, but there was steel in her. She was very strong. On that first night, after the diagnosis, she said in an unemotional, very direct way, “I will not linger with this disease. You will find a way of helping me end it, so that I do not lose respect or dignity.” And of course, I was not about to help her end her life at any point, just because I couldn’t conceive of that. But right from the beginning that was her concern, that she would lose her dignity, and she was an enormously dignified person.

However, over time cognitive decline becomes very severe, and there was a time with my wife when she—she was a China scholar, and loved Chinese painting, and was herself a good calligrapher and painter—she couldn’t do that anymore. It was an unusual form of Alzheimer’s that made her blind in addition to having dementia, and she could no longer see the Chinese paintings that she had collected over a lifetime that meant a great deal to her. She couldn’t make sense of the radio or the television. Her world narrowed very substantially, and with it narrowing there were also physical limitations. Increasingly she couldn’t do things like handle a knife and fork, or a glass of water, or dress herself or bathe herself.

So, I took over all those responsibilities. And for me actually, it was a redemptive time. I had been so unliberated and cared for for 36 years by my wife, and for the next 10 years I reciprocated. So, I felt this was a gift exchange, a reciprocation, and I felt quite good about the early years, that I was doing something I should have done earlier, and that it was within my competence. I felt I could do these things. But then increasingly, there were things that I felt incompetent to handle. Because Alzheimer’s becomes not just a complete cognitive disaster, but becomes a disaster and catastrophe for personality and emotion. My wife had always been the calmest of persons, and as she became more distraught, and frustrated, and angry, I didn’t feel that I had the skills to manage this.

Even though I’m a professional psychiatrist and anthropologist and deal with people, I just felt like I wasn’t prepared. And this took, I felt, a moral shift. A shift in what I needed to focus on. I had been so in love with my wife, and our relationship was the strongest you could imagine, but I had never really thought about what happens when the other person over time begins to be not the person you were married to. And that takes quite a leap forward in keeping yourself oriented and loving, because the person you’re in love with is frankly no longer there. You’re dealing with somebody else in this setting.

I just felt over time that it became unbearable, and even unendurable. I’ve been very successful in my life in just about anything you could name. I never really was defeated. But for the first time, I really had the sense that I couldn’t do this. I kept going, because that was sort of my way of coping—just keep going, keep doing it, keep doing it, ritualize it, make it a habit, just keep doing it. But over time, I realized I needed help.

Facing Tough Decisions as a Caregiver

Being Patient: I take what you’re saying with great value, because I do think that successful care giving means staying yourself as a person. Is that what you really mean, that you need to allow yourself to exist as you existed, as well as acting as a caregiver for your loved one?

Dr. Kleinman: Yes, and I think that that’s associated with tough choices. There comes a time when you have to face the reality that you can no longer care for this person at home. That happens to everyone with a family member with dementia who reaches the last stage. And at that stage I found that I could no longer lift my wife or do all of the nursing that was needed, and I had to make a decision for her to enter a nursing home. That was an extraordinarily difficult decision to make. I felt like a total, complete failure.

Being Patient: I think people feel guilty no matter what, like you were saying maybe I didn’t put her in early enough or I really want to have him or her at home, so I think this is something a lot of people struggle with. What was the turning point for you, what made you say, “I just can’t do it anymore”?

Dr. Kleinman: So, my book is very personal, and I give the details of this. For me, there was a singular event on July 4, 2010. My wife was in very bad straits at that point but was still at home with me, and we have a summer house in Maine that she loved, and I thought why don’t we go up there. So, I asked, and she understood what I was asking and agreed with a big smile. We drove three and a half hours up to our house in Maine, we get up there and I had to open it up and get things ready, put hamburgers on the grill. And just as we were sitting down to eat, my wife became extremely agitated, and I could tell that this was going to be a disaster if we stayed there.

So, I packed everything up, calmed her down as much as I could, got into the car, and she started fiddling with the door on her side. So, I had to hold both of her hands in her lap and drive with my left hand the three and a half hours back. By the time we got back my wife was delirious, she didn’t know where she was or who I was. When we got to the house she was throwing things, and finally she fell down to the floor and lay there in a state of agitated delirium. And I just fell to the floor myself, and just sat there kind of hopeless and helpless.

She fell asleep, and I called a former student of mine who brought over a geriatric psychiatrist who was an expert on this particular stage of Alzheimer’s. And after interviewing her, this colleague of mine took me aside and said, “You cannot take care of her anymore. You’ve done as much as you could. She requires now professional services.” I think that if you’re a highly successful person, who’s always won no matter what, that’s as bad a time as you can ever have.

Caregiving as a Moral Education

Being Patient: We always frame caregiving as taxing and in the negative limelight, but what you’ve said is that it was rewarding. Tell us what you meant, what the rewards were, and what you learned from it.

Dr. Kleinman: So, I think reward is too economical of an idea. This is something that takes away your energy, is very expensive, and draws on all the strengths that you have. Nonetheless, for me it was a redemptive experience, because it was part of an exchange, a gift exchange. My wife had given me her love, her attention, and her care for 36 years, and for 10 years I gave her everything I had. And at the end of it I felt an enormous sense of benefit and purpose in my life.

I would never want anyone to go through this experience, but I can tell you that if you have to go through it, and you work at it, and you work at enduring, and making this thing a reality, you’re going to get something out of it. That’s why I used the term moral education. “The Soul of Care: The Moral Education of a Husband and a Doctor” made me a different person. If you had known me beforehand, you would have said this is a very driven, hardworking, successful academic. And at the end you would have dropped all those things and said that this is a loving, caring husband.