When Lisette Carbajal was a freshman at University of Virginia, she was just a few months into her semester when she found out her father, who was in his early 60s, had Alzheimer’s.

“When my father was diagnosed, my focus shifted from graduating on time to ‘how will I care for my father,'” said Carbajal, now 26.

Though her father had family support, much of the management of the disease fell to Carbajal, a first-generation American and the first in her family to go to college. Neither of her parents speak English, and Carbajal stepped up to figure out insurance and manage appointments. “It was me calling my mother saying I need X and Y paperwork,” she said. Carbajal was the one to learn from doctors how Alzheimer’s would slowly tighten its grip on her father. “Hearing about what would happen took a toll on me. I was depressed and upset,” said Carbajal. “I had to grow up quick.”

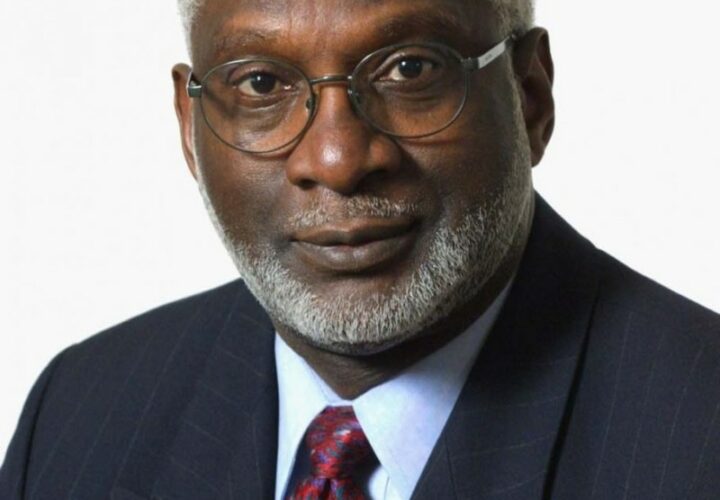

Maria P. Aranda, Ph.D., an associate professor of social work at University of Southern California and interim executive director of the Roybal Institute on Aging, characterizes this as the “dashed expectations and dashed hopes” that millennials face when the responsibility of caregiving is thrust upon them. Those responsibilities, says Aranda, not only affect the relationship millennials have with their care partner, but also their own potential for relationships with significant others, along with financial stability, job opportunity and emotional wellbeing.

A new study by researchers at the University of Southern California and UsAgainstAlzheimer’s found that one in four of those providing care is a millennial, or someone between the ages of 18 and 34. One in six millennial caregivers is providing care to a dementia patient. Around 40 percent of those millennials are the sole caregiver for their loved one.

For millennials who are in the beginning stages of their career, providing care can have a severe impact on their livelihood. Half of the 235 millennials surveyed said their work was affected by caregiving, and about a third said that interference included cutting back on hours, losing job benefits and/or being fired. Fourteen percent reported that they had to stop working entirely.

The average age of millennial caregivers is 27, an age when most young adults are reaching milestones like achieving degrees, moving up professionally or starting a family of their own. For dementia caregivers, the desire to develop alongside their peers, along with the lurking grief of losing the parent you once knew can be overwhelming. “When I first started [caregiving], I didn’t know who to vent to,” said Carbajal. “I would like to see more youth support groups.”

A more public face for millennial caregivers also means we’re paying more attention to early onset Alzheimer’s, said Aranda, which is what most millennial care partners are dealing with. While millennial caregiving is not necessarily a new trend, we’re starting to talk about it more—and that’s a good thing, said Aranda. Millennials will be tasked with a heavy load in the coming years, as Alzheimer’s rates increase and the health care system is too strapped to provide care for them. By the year 2033, the U.S. Census Bureau found that working age adults will support more people over 64 than people under 18. Talking about millennial caregivers provides support and also sheds light on how we need to prepare for a future of caregiving.

where do i call to get paid for taking care of husband with dimentia