With more of us living into our 90s and beyond, researchers have long been curious about why (and how) some “super seniors” manage to maintain their cognitive ability.

While there is no definitive way to prevent dementia, half of Americans are worried about developing dementia, and new research shows that certain lifestyle factors may have a big impact in staving off symptoms, even for people with a key Alzheimer’s biomarker.

In a new study published in Neurology, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology, researchers found that people with better lifelong thinking and memory skills were less likely to develop cognitive impairments. The finding even applied to participants who had developed amyloid plaques in their brains, which typically signifies cognitive decline.

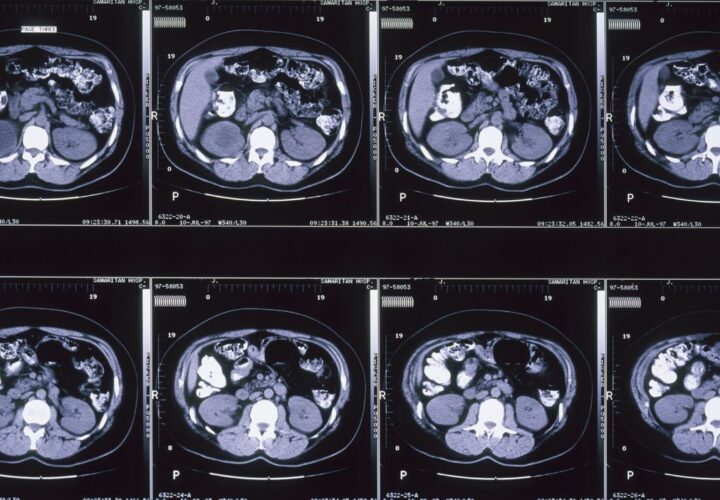

The study involved 100 people who did not have dementia and were followed for up to 14 years. Study participants had their thinking and memory skills tested; they also participated in imaging scans to see whether they had developed amyloid plaques.

“With more and more people living into their 90s and even 100s, it’s increasingly important that we be able to understand and predict the factors that help people preserve their thinking skills as they age and determine if there are any changes people can make during their younger years that can improve their chances of cognitive resilience,” study author Beth E. Snitz of the University of Pittsburgh said in a news release.

The researchers found that lifestyle factors were significant indicators of long-term brain health and could help prevent dementia symptoms from setting in.

People who never smoked, for example, were more than 10 times more likely to maintain their thinking skills even, with amyloid plaques. Those with lower blood pressure measurements also seemed to correlate to better cognitive health. In addition, having ongoing meaningful work opportunities also seemed to help preserve cognitive abilities.

People who never smoked were more than

10 times more likely to maintain their

thinking skills, even with amyloid plaques.

In an editorial published along with the research paper, Claudia Kawas and Maria Corrada-Bravo, scientists at the University of California, Irvine, applauded the research and said that studying the “oldest-old will help us learn about how to add life to the growing number of years we have.”

Noting that people aged 90 or older are now the fastest-growing segment of the population in most of the world, Kawas and Corrada said that “the oldest-old have a lot to teach us.”

“Extending life expectancy came at a price,” they wrote. “We extended disabled life more than able life.”

“Maintaining cognitive abilities throughout the lifespan would have staggering public health benefits and is ultimately the goal for all of us,” they continued. “With the help of oldest-old individuals, we can learn the biological underpinnings of successful aging and potential strategies for resistance and resilience.”

Both the editorial and the research paper, however, note the limited nature of the study. The participants were primarily male, white and well-educated, when throughout the world three-quarters of all individuals over age 90 are women and minority seniors are a rapidly growing group that is very understudied.