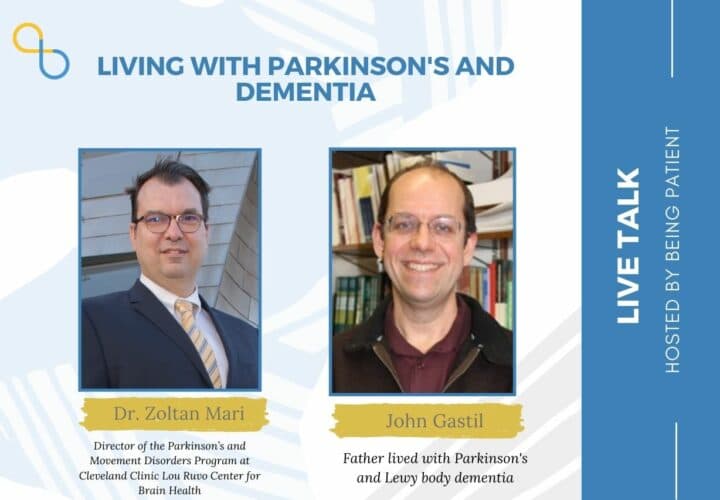

As part of our LiveTalk series, Being Patient spoke with John Gastil and movement disorder specialist Dr. Zoltan Mari about the symptoms, diagnosis and treatment of Parkinson’s and Lewy body dementia.

Parkinson’s is the second most common neurodegenerative disease after Alzheimer’s — roughly 60,000 people in the United States are diagnosed with the former annually. As a child, John Gastil watched his grandmother navigate Alzheimer’s. Decades later, his father was diagnosed with Parkinson’s and eventually Lewy body dementia.

Being Patient spoke with Gastil about his father’s journey with the disorders and with Dr. Zoltan Mari, director of the Parkinson’s and Movement Disorders Program at Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health, who shared insights in the diagnosis, clinical care and science of the neurodegenerative diseases.

- While Alzheimer’s is characterized by beta-amyloid plaques and tau tangles, the hallmark of Parkinson’s and Lewy body dementia is a protein called alpha-synuclein.

- The sequence of symptoms between Parkinson’s disease dementia and Lewy body dementia differ early on, but as the disorders progress, their symptoms and brain changes are similar; clinicians often think of the two as being on the same spectrum as opposed to distinct diseases.

- Early on, Parkinson’s damages the nigrostriatal pathway, a brain region with dopamine-producing neurons that regulate movement.

- Dr. Mari urged people to consult with a movement disorder specialist for accurate diagnoses of Parkinson’s and Lewy body dementia.

Being Patient: We often hear Parkinson’s and dementia mentioned together, can you help us understand the two conditions?

Dr. Zoltan Mari: Dementia is a syndrome. It’s not a disease. It is a set of symptoms that can be caused by a variety of different etiologies and Parkinson’s disease is one of them. When dementia develops in the setting of Parkinson’s disease, then we call it PDD, or Parkinson’s disease dementia. Having said that, you can have Parkinson’s disease and live a long life and not have dementia. So it’s not an absolute inevitable event.

Once the motor symptoms develop, the disease will progress. At some point, the underlying pathological process that is happening in the brain could reach and affect some of the networks and parts of the brain, which are responsible for memory, cognition, mentation, executive functions. That’s when you will start experiencing the symptoms of dementia at some point.

Being Patient: Does Parkinson’s affect different parts of the brain than Alzheimer’s?

Dr. Zoltan Mari: Different parts of the brain are responsible for different functions. When they are attacked by neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s disease or Alzheimer’s disease, the way those different parts of the brain are attacked, at what time course and to what extent, will have an impact as to how you would look clinically.

The well-known part of the brain that is susceptible to Parkinson’s pathology early in the disease is called the nigrostriatal pathway. That’s part of the basal ganglia and that’s why motor symptoms such as slowing, losing some coordination, dexterity, becoming stiff, losing balance and sometimes tremor are oftentimes the early motor manifestations of Parkinson’s disease and not so much dementia or cognitive impairment.

But that doesn’t mean that higher order parts of the brain like the frontal lobe or the temporal lobe, which includes the hippocampus and other networks, are immune to Parkinson’s. They are not involved early on. They are relatively resistant to the underlying pathological process. They are only going to be involved later in the disease and not to the same extent as for instance in Alzheimer’s, where they are affected and attacked early on in the disease and to a greater extent.

The underlying pathology that kills neurons in the brain is very similar between Lewy body dementia and Parkinson’s disease. That process is referred to as synucleinopathy. There is one protein in the brain, which we all have, and something bad happens to it. In a normal state, it is part of our brain. We need it. We physiologically rely on. But something happens to it for it to start misfolding. It has a different shape and that makes it toxic. It will not be water-soluble. That’s the underlying reason why everything goes awry and eventually leads to cellular death.

Alzheimer’s disease is not synucleinopathy. It is also a proteinopathy where a protein tau will do the damage and that’s what starts the degeneration. That’s why it’s called tauopathy. And there are many other neurodegenerative disorders in that group as well.

Being Patient: John, tell us about your father’s journey with Parkinson’s and Lewy body dementia.

John Gastil: I was exposed to Alzheimer’s at a very early age. My grandmother would call several times a day and tell us the same stories, so we started to learn about it when we were little. But then other women of her generation also had it and so it was something that was considered very common in our family: Alzheimer’s.

Going forward several decades, Dad started declining a little bit physically, but not in a way that was noticeable. He had always had kind of a funny way of moving and so, as his gait became a little more problematic, nobody noticed. Finally, he and my mother were just at a party and a doctor asked, ‘How long has it been since your husband was diagnosed with Parkinson’s?’

It was so gradual that it really didn’t register. I would say the same thing started with Lewy body dementia. He was always an absent-minded professor, so we were maybe a little more forgiving of some of the early signs of trouble.

My father was a field geologist and he was a scientist his whole life. He was climbing mountains, running around being crazy, cracking terrible dad jokes. When Parkinson’s came to him, that freedom of movement was the first thing that you started to see go.

Late in his life, I got to travel with him and my mother to Central America and see the Mayan ruins. He had become fascinated with archaeology late in his career. If this was something he was going to do in his life he had to do it soon. We went on that trip at the last possible chance. Movement was so difficult for him. But cognitively, he was absolutely sharp. He was hilarious when he was on, but he would kind of come and go throughout the day. He’d be better in the morning and worse at night.

On a couple of nights on that trip in the evening, he really caused some of the other guests on that trip to almost panic: this is not the same guy who was walking around at the base of a pyramid with us earlier today. He seems really lost.

Dr. Zoltan Mari: The variation should always raise the suspicion for Lewy body dementia. It happens much more with Lewy body dementia than other dementias, and so does the early hallucinations. The intraday variability is a very classical feature for Lewy body dementia. One day you are like a different person from the other day, and why is that?

That speaks to the complexity of cognitive performance. It’s not a one-dimensional linear matter. It is affected by your electrolytes, fluid balance, perfusion to the brain, how much you ate, how much you slept, maybe a virus is running through your body. There are so many other factors that normal people who have a healthy cognitive reserve will not notice because their reserves will balance for it.

If I had bilateral pneumonia and I had a fever of 105°F and I was dehydrated, I would probably be hallucinating. But to get there, it would take a lot going wrong with my internal homeostasis, fluid balance, the temperature of my brain. A lot of things must go wrong for it to decompensate. People with cognitive impairment and neurodegenerative disorders don’t have a big cognitive reserve. It takes very little for them to decompensate and those factors that I mentioned may all, or any one of those, or in combination, be responsible for these fluctuations. In my opinion, the most common is probably perfusion of the brain because that can be affected by body position, hydrations levels.

Being Patient: Dr. Mari, what do we need to know to get an accurate diagnosis?

Dr. Zoltan Mari: There is no absolute diagnostic biomarker for any one of these disorders. There are disorders, including Huntington’s disease for instance which also can cause dementia, that you can do a genetic test and know if somebody has it or doesn’t have it. That is with 100 percent certainty, which we call it an absolute biomarker. There is no such absolute diagnostic biomarker with 100 percent sensitivity and 100 percent specificity for any of these other neurodegenerative disorders.

I always encourage patients to seek a subspecialty expert in the field who can piece together clinical signs, history, imaging, psychological evaluation and other data to arrive at a high certainty clinical diagnosis. In terms of the diagnostic accuracy, experts who do this and only do this all the time will have a much greater chance of getting it right. As time goes on, usually our ability to accurately diagnose will improve because we have the luxury of looking at the time course of a disease, which could look very similar in the very early stages.

Being Patient: John, were there activities that helped engage your father?

John Gastil: There is actually a lot of things that aren’t medical that you can do. One of the things that comes to my mind is the tremble clefs choir that my mom would take him to where he could sing. You couldn’t understand a word he said and then he’d sing some terrible old song like ‘Oh! Susanna’ — the kind of stuff that would torture us on long field trips. That is a kind of treatment. It would give him some confidence and self-esteem and some community because it would be with fellow Parkinson’s patients who varied in their singing ability aside from neuromuscular difficulties.

When we talk about the different symptoms that can indicate one thing or another, anytime a layperson is going online and looking at a list of ‘here are the symptoms of Lewy body dementia,’ what I want to encourage is that you’re dealing with a person. That website is trying to generalize across all persons.

For example, going back to my father, he was a geologist, he studied Baja California. He was constantly paying attention to his world. He became an amateur botanist, very amateur, and was fascinated by the culture and history of Mexico and all these things. He never lost that drive. He was never gonna be apathetic. No disease could handle him. How about depression? Well, he was always kind of depressed, frankly. He became more optimistic. He became sweeter. It was the change that alarmed us.

Being Patient: Dr. Mari, do certain treatments for Parkinson’s also work for Lewy body dementia?

Dr. Zoltan Mari: The short answer is yes. The symptoms can be very similar. It is very difficult to tell apart, especially in the early stages. Parkinson’s disease is not always the same either. There are patients who start [experiencing] cognitive impairment earlier in the disease. Some patients have tremor, others don’t. Some patients are asymmetric, some are not as much.

There is a great variability even within the Parkinson’s disease group and the Lewy body dementia group and there is quite a bit of overlap. Having said that, the treatment for both is so called symptomatic. Unfortunately, at this moment, we don’t have anything that would interfere with the synucleinopathy itself, which is sort of the root cause of all the problems, or the neurodegeneration or the related neuroinflammation.

But we have treatments for the symptoms. The nigrostriatal dopaminergic system has a dopamine deficit. Dopamine is a neurochemical that the brain cells use to chat with one another, and there is not enough of that in both of these diseases. Some dopamine-based symptomatic treatments will help Parkinson disease as well as diffuse dementia with Lewy body disease patients.

If you have cognitive impairments like Parkinson’s disease dementia, which is very similar to Lewy body dementia, there are some medications to improve memory and cognition, which will work in both. [There are also interventions such as] physical therapy, occupational therapy, antidepressant treatments, and the list goes on and on. There are a lot more that are similar in the clinical management of the disease than there are different.

There are many non-pharmacological interventions and treatments and it’s truly a multidisciplinary effort. But all that is to make the symptoms more bearable and the quality of life better.

These are all referred to as symptomatic treatments, which do not alter the course of the disease, and do not interfere with that underlying pathology that I discussed before, and that is the holy grail. That is what everyone is trying to get to. There is tremendous effort and investment of research dollars throughout the world in trying to resolve that.

There are some very promising preclinical results and ongoing clinical trials where the goal is not necessarily to stop it in its tracks completely and halt the progression but to slow the progression. In other words, if you are losing X amount of ground in 10 years, we want you to lose half of that in 10 years. That would be slowing down the progression and that would be a breakthrough.

I think we are close, we are not quite there yet, but the potential of that in the future maybe in our lifetime, would be to catch the disease even earlier than the symptoms first manifest. There are so-called prodromal states, which are certain signs that will increase your likelihood of developing Parkinson’s disease later, sometimes years later. If we had a way to completely halt the progression and applied it at that stage, then Parkinson’s disease would never develop and that it would prevent disease globally in the future just like how vaccines prevent infectious diseases.

Being Patient: Are there useful brain imaging for Lewy body dementia?

Dr. Zoltan Mari: These disorders for the most part are diagnosed clinically, which means that a clinician such as myself or a cognitive neurologist for dementing disorders, would gather all the information, take the history and do an exam and use some criteria to see if the patient meets those criteria for a clinical diagnosis. There are confirmatory tests, which include imaging.

For instance, in the case of dementing disorders and Lewy body dementia, a brain glucose positron emission tomography (PET) scan will light up the parts of the brain based on their metabolism. It’s a metabolic scan with a sugar that will bind to parts of the brain that are metabolically active, and how it lights up can point to different disorders and can help sometimes with supportive evidence to point to Lewy body dementia versus Alzheimer’s and others. But it’s not an absolute test.

Just like the PET scan, MRI is also part of the workup. There are certain disorders that we have to rule out and some of them can produce very clear MRI findings. Now in Parkinson’s disease, the MRI is unremarkable. There is nothing that stands out. On the other hand, there are some conditions that can produce very clear MRI changes and structural abnormalities that you can see, which can also produce signs and symptoms of Parkinson’s. So if there is that concern, or a red flag for one of those conditions like normal pressure hydrocephalus, or a cerebral vascular disease and strokes, or sometimes we can see even some neoplasms or a space occupying lesions that can produce symptoms like that. There are many different conditions that could produce an abnormal MRI and ordering it would help you reassure your diagnosis.

At the same time, dementing disorders with Alzheimer’s for instance, we can do so-called volume metrics — a very detailed analysis to measure the size of the hippocampus and compare it to an age-matched population of what it should be and that gives you a percentile. If it’s very low, that will be a supportive factor that will point to Alzheimer’s. For other neurodegenerative disorders such as progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), there is a very clear atrophy of the midbrain and especially in the later stages of disease. That can help differentiate from Parkinson’s and others that can clinically look similar.

Being Patient: If we have a loved one with dementia, what questions should we ask our doctor?

Dr. Zoltan Mari: If I had a loved one with dementia, the first thing I would ask the doctor is if they are experienced with diagnosing and managing dementia, because that could really make a big difference. At least for making the diagnosis and setting the care plan on a good track, a cognitive neurologist who is specializing in dementia would need to be consulted some time not too far out from the diagnosis, in part because there are sometimes mimicking conditions that could be reversible. Missing that is devastating. The same thing goes for Parkinson’s and Lewy body dementia. A movement disorder specialist would need to be consulted, at least to confirm the diagnosis, make sure that it’s correct, and then set the treatment plan on the right track.

John Gastil: When you do meet with the doctor with the person who is getting the diagnosis, bring someone else — a family member or a very close friend. You’re going to be paying attention to the content of what the doctor says, have your friend or family member tasked with the responsibility of paying attention to the manner of the doctor: Do they talk to the patient as a person? Do they talk about you and your situation as though it’s unique and personal, or do you feel that you’re talking to a website?

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Contact Nicholas Chan at nicholas@beingpatient.com

2 brothers died from Alzheimers last year and a third brother is in a nursing home with Parkinsons and Alzheimers. I was one of seven children, I have also lost a brother and sister to pancreatic cancer and my youngest sister died from MS at the age of 62. Is there a connection between these diseases?