Dr. Eric B. Larson, a senior investigator at Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, explains how meaningful the act of reminiscence can be for older adults, including those with dementia — and how meaningful it can be, likewise, for the listeners who share in their stories.

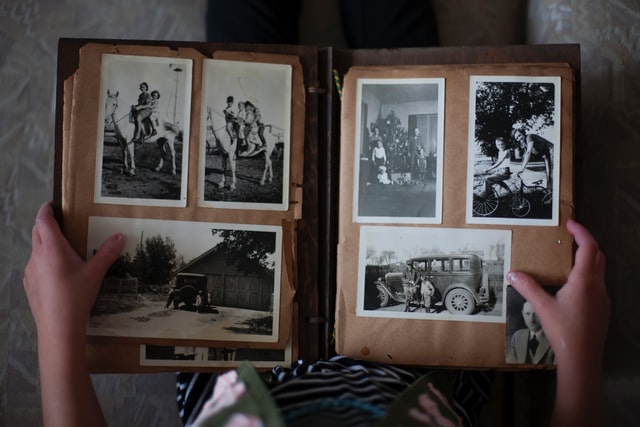

As we age, memories of long past events become more important, especially with each passing decade of late midlife and old age. Studies show that when centenarians are asked to reminisce on past events — especially to cite their enjoyable or most meaningful events — the trove of events they recall involving their first 20 years of life vastly exceeds the previous 20 years. It’s as if our minds lay down vast amounts of earlier-in-life events that get embedded deeper and stronger into our brains’ circuitry.

It is clear to anyone who speaks frequently with older persons that many delight in the telling (and retelling) of these experiences and relationships of their past lives. Since the time of Aristotle’s Rhetoric, wise people have realized that reminiscing is not harmful, but helpful, and that as we age, people think a lot less about their future and more about their past. This is not unhealthy but simply a feature of aging. People shouldn’t be denied this pleasure.

This can be challenging for many younger persons (and even spouses of older persons who themselves are old) who may find it tiresome to hear the same stories repeatedly. Think of the challenges faced by busy attendants in long-term care or other facilities where older persons live. But it is important to acknowledge that with time, our memory develops into what one eminent memory specialist, the psychologist Douwe Draaisma, calls a ‘nostalgia factory,’ which may bring great pleasure to our lives, especially the older we become.

“With time, our memory develops into

what one eminent memory specialist,

the psychologist Douwe Draaisma,

calls a ‘nostalgia factory,’ which may

bring great pleasure to our lives,

especially the older we become.”

“Reminiscence” Therapy

This sort of observation has led to efforts to develop so called “reminiscence” therapy programs for persons living with dementia and their caregivers. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality-sponsored Evidence Practice Center (EPC) at the University of Minnesota recently was charged to survey the medical literature to determine “what works” and is ready for dissemination and implementation. It found 26 publications involving 24 unique studies of reminiscence therapy, 21 of 24 were non-U.S., with most of them from Europe.

Like many studies of non-pharmacologic treatment programs, the EPC rated the studies, including four randomized trials, as having very “low strength” of evidence. Furthermore, the four randomized trials were unable to demonstrate benefit. So, we certainly can’t advocate that programs building reminiscence therapy ‘programs’ into everyday care are supported by strong evidence.

That said, I believe in our everyday life as we have conversations with older persons, including persons with mild to moderate dementia, engaging in reminiscing is pleasurable and worthwhile. Persons reminiscing brighten up with a listener who appreciates their memories and is interested in their stories. And in turn, it’s meaningful for families to learn as much as possible from their parents and aging relatives about their family’s past, especially in a time when we are so mobile throughout the life course.

“Persons reminiscing brighten up

with a listener who appreciates their

memories and is interested in their stories.

And in turn, it’s meaningful for families to

learn as much as possible from their parents

and aging relatives about their family’s past.”

As a dementia researcher I find this a source of immense pleasure. My wife will often hear me say after a home visit or (nowadays) telephone visit – “I just heard the most amazing story about this (guy, older lady) … who grew up … Or moved with his family to escape persecution or find a better life …” These reminiscences are often the high point of my day.

I wish and hope others can experience listening to reminiscences as a true “win-win.” Of course, it is also important to strive to keep these reminiscences as accurate as possible — avoiding tall tales and respectfully redirecting conversations when a tale becomes too tall. Couples often need some sort of signal to keep reminiscing from becoming overbearing and too lengthy. The pleasure of reminiscing can overwhelm good sense if not handled judiciously.

The bottom line: Many people in the late stages of Alzheimer’s disease who might otherwise be totally confused can have a day, or many hours in a day, when they suddenly, out of nowhere, recall with great detail important times and delight in sharing them with a child, close relative, friend or caregiver. In interviews for my research, I hear family members report that it was as if their father or mother was back to normal, and I’m asked why they can’t be like this all the time. Sadly, that’s not possible, but there is something indelible, presumably in memory centers involving the hippocampus, that stays with us throughout most, if not all, of our lives. We should strive to treasure the miraculous ability of the brain to hold onto the past as well as it does.

Eric B. Larson, MD, MPH, MACP, is a senior investigator at Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute and a general internist specializing in geriatrics, health services, and clinical research, studies aging Alzheimer’s disease. He has contributed to groundbreaking research on, among other things, the relationship between certain controllable lifestyle factors and dementia risk. He is the author of Enlightened Aging: Building Resilience for a Long, Active Life.

A well written reminder of the importance of listening and remembering, made all the more difficult by the isolation of a pandemic. Thank you, Dr. Larson!

Wonderfully written! We try our best by playing Beatles music every day, even in a late stage of dementia. Not only may there be a core of memories in the hippocampus, as you mention, but there seems to be a wonderful core of personality that also flashes out occasionally, for which we are quite grateful.