Experts say that more positive terminology can help reduce the stigma around dementia — and make a diagnosis not feel like a “death sentence.”

The way we should talk about dementia and other neurodegenerative diseases — the terminology we use — can be confusing. We might find ourselves slipping into using phrases that center the diagnosis, rather than the person. For example, this publication tries never to use the phrase “dementia patient” in our reporting. Rather, we prefer, “a person living with dementia.”

But it’s an ongoing conversation, and there is constantly new information, and new perspectives, to consider: How do we talk about people living with dementia in a way that is respectful and encouraging?

In a recent panel on “Rethinking Concepts Like ‘Activities of Daily Living’ in Memory Care”, experts weighed in. The conversation included Carrie Aalberts (or “Dementia Darling” to her social media followers), Adria Thompson (a licensed speech-language pathologist and founder of Be Light Care Consulting), James Lee (CEO and co-founder of dementia education organization Bella Groves), and Daniel Lawson (co-founder and president of business affairs at the panel’s hosting organization Viking Pure Solutions shared wisdom).

Nicole Will, founder of willGather Podcast, kicked off the discussion by asking, “How do we define activities of daily living? Why do we refer to them this way?”

“If you’re a caregiver, listening to this panel, this conversation is not intended to shame your choice of terminology,” Thompson said. “There is no intention here that we want you to feel bad, or even for professionals using the wrong terms in the past.”

‘Activities of daily living’

The conversation centered around shifting the narrative of what people living with dementia cannot do, and instead highlighting their abilities and what activities they can do independently.

“‘Activities of daily living’ is basically just a term that refers to tasks that we do every day to care for ourselves. So underneath the umbrella of activities of daily living there’s things like bathing, getting dressed, going to the bathroom, feeding ourselves, shaving your face, brushing your teeth,” said Thompson.

“Occupational therapists are largely in charge of assessing and treating any deficits in activities of daily living,” said Thompson. “We have to be able to have that term to look at a person and say not only what things they can’t do, but how much that they can do on their own.”

“Our field is ever-changing and ever-growing.

We are learning new things about dementia

every single day. So why is our vocabulary not

changing with it? Why are we not evolving?”

The panelists made it clear that as medical professionals the language they use can vary significantly from non-medical professionals. “This is what we do as a job and because of that, it’s important that we model positive person centered language,” said Thompson. “If you’re a caregiver, don’t worry, you’re not going to say the right thing. You’re in the trenches of just caring for someone and trying to keep someone alive. Don’t worry that you’re doing the wrong thing.”

When asked about activities of daily living, Lee recounted an experience he had and how the conscious choice to use respectful language can impact an entire team of medical professions and the attitude with which they treat people under their care.

Framing intentions with words

“As leaders in this field, the words that we choose frame what our teams believe about what they should be doing and focusing on. There’s a term I heard – and I never used it because it intuitively didn’t feel right,” said Lee. “I remember walking around a community and the person giving me a tour said something to the effect of, ‘That table is where we have our feeders.’ I was like, ‘Your, your feeders? What does that mean, your feeders?’”

The term “feeders” used by the care workers was intended to refer to people who needed assistance dining, but the manner in which the term is phrased completely takes away from the person, and places all emphasis on their ability or lack of ability to complete certain daily tasks.

“The words we use frame the intention of our team,” said Lee.

Aalbert noted that terminology used by medical professionals can also impact the family members and caregivers of those living with dementia.

“If you’re always attaching negative things to their loved one, they’re not going to feel very positive about interacting with their loved one and wanting to do things because they’re thinking, ‘They can’t’ and it’s just an automatic ‘No,’” said Aalberts. “We can’t be creating this negative, ‘tragedy’ stereotype for these family caregivers. Those negative views can be a huge barrier for obviously the staff, but the family caregivers as well in learning and wanting to meet their loved ones where they’re at.”

Lee spoke about the need for medical professionals to use terminology that doesn’t indicate a person under their care is entirely dependent on someone else. “Anytime we use language like ‘Hey, have you fed Mrs. Johnson?’ or ‘Have you bathed Mrs. Johnson?’ the way that we use that term — it puts the other person at a deficit orientation. We’re only thinking about them in terms of what they can’t do.”

“We can’t be creating this negative, ‘tragedy’

stereotype for these family caregivers.

Those negative views can be a huge barrier

for obviously the staff, but the family caregivers

as well in learning and wanting to meet

their loved ones where they’re at.”

At Bella Groves, the dementia education organization that Lee co-founded, Lee said, “We will correct it 100% of the time if somebody says, ‘Hey, can you go shower somebody?’ We just gently remind them that we’re going to go assist the person with their shower. It’s a little bit longer to say, but it’s the right way to say it.” Using generalized terminology can lump people living with dementia together and underestimate their abilities.

‘We’re not always going to get it right’

Determining which language terminology is appropriate can be a challenging task, as Thompson pointed out that even medical professionals have differing opinions on certain language terminology. Medical professionals need accurate and precise terminology, which makes certain terminology necessary to use. On the other hand, non-medical professionals working in a living community for people with dementia are not medical professionals. The language non-medical professionals use, and what is appropriate for them to use, will vary.

“I’m a speech language pathologist and language is very important to me, it’s an area of my specialty. And so as we’re talking, I’m thinking, “What makes these terms negative? What is it that makes them feel that way?” said Thompson. “I think it’s important to consider that it is our personal experiences and our lived experiences that make some terms feel more icky than others. Acknowledging that says, ‘We’re not [always] going to get it right.’ Even for those of us on the panel, we disagree about what things feel icky and what things don’t, and that’s absolutely going to be true for the people who are listening.”

“I think it’s important to consider that it is

our personal experiences and our lived experiences

that make some terms feel more icky than others.”

Despite differences in thought in the care professional community, Thompson says that her underlying goal is to remove the victim and tragedy narrative associated with dementia from language.

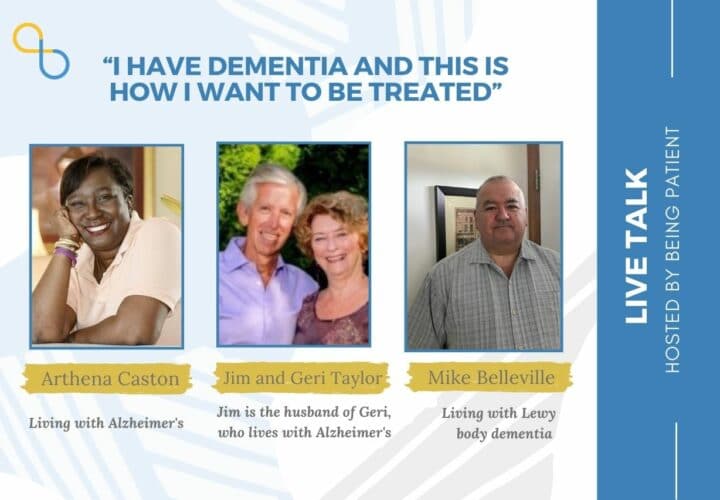

“Everyone’s lived experience is different. We are advocating on the behalf of individuals with dementia for better terminology, because we don’t want them to be victims, or we don’t want them to look as if their life is over,” said Thompson. “We don’t want people that were recently diagnosed to hear this tragic narrative and scary language so that they dread the rest of their lives – because they can live for a long time.”

People living with dementia and family members and caregivers should play an active role in the discussion. Fostering conversations around terminology between caregivers and those receiving care can further educate the broader community.

“Our field is ever-changing and ever-growing. We are learning new things about dementia every single day. So why is our vocabulary not changing with it? Why are we not evolving?” said Aalberts. “I’m sure some of these terms we’ve been using since the 80s, which is great. But if we’re still using them, when we talk about this with our staff, we need to go into why we’re using this term and the history.”

I think this is a fantastic awareness to address to the public. People being more sensitive to their families, patients living in facilities and their caregivers. If we all just paused to ourselves before speaking would go a long way to improving our language or lingo.

The whole message changes for ourselves and the other person!

Indeed it does, Pamela! Choosing positive terminology can greatly help reduce the stigma around dementia. Thank you for reading!

My husband has had Alzheimer’s for four years . It was a shock but we live with it not letting it define us. One of the most liberating things is telling people he has it. He now openly says he has the disease and the response from perfect strangers has been amazing. They don’t shy away, they talk to him. He is not ashamed of having it, His memory causes problems, but.If he can’t think of a word, I prompt and we both cheer when he finally remembers. He has learnt to sail with disability sailing at age 81! Yes it is a dreadful disease, and I have days when I despair of all the extra things I now have to do but I am proud to hear him say he has Alzheimer’s because every time he says it more of the sting about having it goes away for HIM. We need to be talking about it,reassuring people there is a life still for them. It will never be the same again but the “new” person can function and enjoy different things.

Hi Liz, thank you so much for sharing this with us. Your positive attitude and determination to help your husband live life to the fullest despite Alzheimer’s is admirable. Wishing you both strength and continued joy on this journey.