In Part 1 of a two-part series about gene therapy, genetic medicine expert Dr. Ronald G. Crystal shares insights into the status — and promise — of gene editing as a possible treatment for Alzheimer's disease.

This article was made possible through sponsorship by Lexeo Therapeutics. Being Patient’s editorial team produced the interview and article, with no review/approval process by the sponsor. Explore the rest of our gene therapy series.

There are as many as 25,000 different genes in your DNA. One of those genes, ApoE, is of special interest to people who are concerned about their brain health. People inherit one copy of ApoE from each of their parents, and if one of those copies is the ApoE4 variant, it increases the risk of Alzheimer’s by 25 percent. With two copies of ApoE4, it doubles the chances of developing the disease. Certain other genetic variants, which are much rarer, all but guarantee a person will develop early-onset Alzheimer’s.

In the 1980s, genetic medicine expert and physician Ronald G. Crystal was working on treating a genetic lung condition. The gene responsible for producing an important protein wasn’t working properly. The only solution was taking this protein from the blood of healthy donors and infusing it every four and a half days. That’s when he got the idea for inserting a new gene into patients that could fix the problem permanently. But, he had to solve a big conundrum: getting the gene from the lab into the human body. By 1993, his research had led to the first FDA-approved trial of this type of gene therapy in humans. Since 2004, he’s been exploring this technology for Alzheimer’s disease.

Crystal is the director of the Belfer Gene Therapy Core Facility and attending physician at the New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, and he chairs the Cornell University Weill Medical College genetic medicine department. He’s also responsible for a number of biomedical patents. His technology is the basis for a broad spectrum of the current work being done in the gene therapy field, and accordingly, he’s a founder/co-founder of multiple gene therapy-focused biotech companies leveraging this tech, including GenVec, Adverum, Xylocor and Lexeo Therapeutics, the latter of which is now carrying out clinical trials for a gene therapy designed to reduce the high risk of Alzheimer’s associated with the ApoE4 genetic variant.

The team at Lexeo is working to address genetically defined cardiovascular and central nervous system diseases. The gene therapy for Alzheimer’s currently in clinical trials, first developed by Crystal’s lab at Cornell University’s Weill Medical College, aims to reduce risk by using another ApoE variant — ApoE2. Unlike Apoe4, this variant might have the opposite effect on Alzheimer’s risk. It appears to help protect people against developing the disease.

In this conversation with Being Patient EIC Deborah Kan, he shares his expert take on the past, present, and future of the field with regard to neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s. Read the transcript of the conversation or watch the full recording of the conversation below.

What is gene therapy, and how could it work for Alzheimer’s disease?

Being Patient: I know you were one of the first scientists to really delve into the role that genetics can play in terms of preventing Alzheimer’s disease. Tell us how this all started.

Ronald G. Crystal: Some colleagues of mine had gotten the idea related to what we’re actually working on, and the concept relates to the genetics of Alzheimer’s. We know from epidemiologic studies that the apolipoprotein E gene is an important genetic determinant in terms of risk for Alzheimer’s. There are three forms of the apolipoprotein E gene, referred to as ApoE: ApoE3, ApoE2, and ApoE4. Most of us are ApoE3, we inherit it from both parents, but some of us have the ApoE4 gene— and if we inherit that from both parents, we have a 15 percent, or maybe a little more, risk for the development of Alzheimer’s. When it does develop, it’s more aggressive and occurs earlier.

In contrast, if you’re lucky and you inherit the ApoE2 gene from both parents, it is protective. What got us interested was the individuals that are inherited from one parent, ApoE4, and one parent, ApoE2. They’re what we call a heterozygote: ApoE2 ApoE4. In those individuals, the ApoE2 gene takes away most of the risks of the ApoE4. So, we got the idea, why not modify the brain genetically of a buoy for individuals who are ApoE4 with the ApoE2 gene so that they would have a lesser risk for the development of Alzheimer’s?

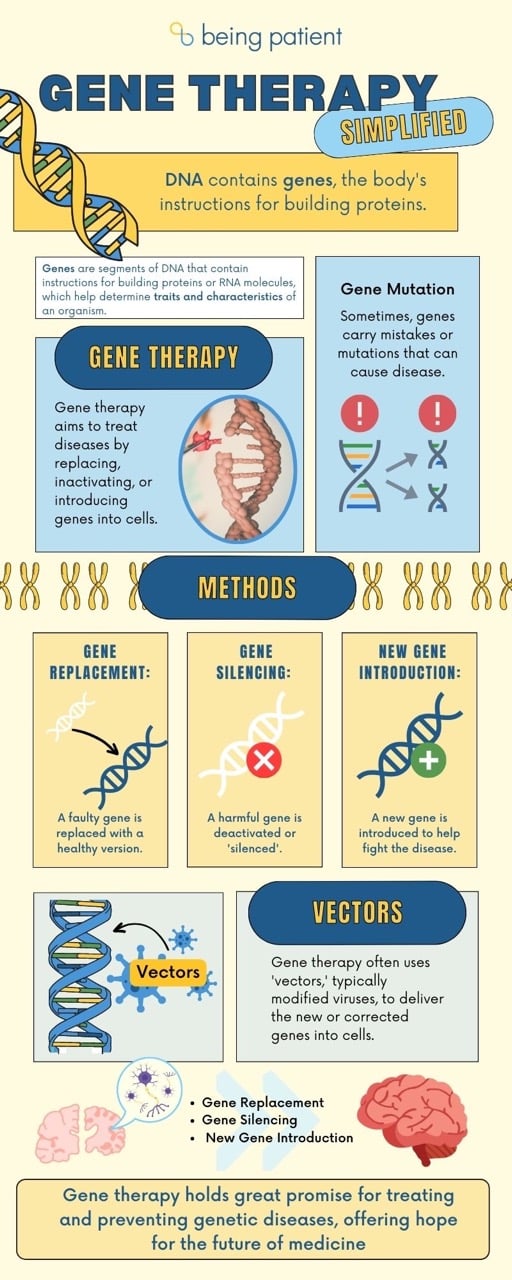

Gene therapy infographic:

Being Patient: How does gene therapy work? How do we change our genetic makeup in order to make a gene that elevates risk behave in a less risky fashion?

Crystal: Gene therapy is essentially a drug delivery system. What we’re doing is we’re delivering DNA genes. We’re all made up of about 25,000 genes, and we’re using those genes essentially as drugs. So, gene therapy is a strategy to try to prevent or treat disease by using genes as the drug.

The target is the brain cells, so we’re trying to get the proper gene into the brain cells. We’re not really altering the genes, what we’re doing is putting in a new gene, and we’re augmenting the genes. What we’re doing is taking the ApoE2 gene and delivering that to the brain. One of the obvious questions is, “How do you deliver a gene?” You can’t just eat a gene and expect that it goes to the brain. The way we do that is with viruses.

“Gene therapy is essentially

a drug delivery system.”

There’s a group of viruses, and the viruses we use are called adeno-associated viruses, or AAV. These have been widely used in terms of brain gene therapy because they’re very avid for brain cells. The viruses are modified so they don’t cause harm. We’re essentially using the viruses like a Trojan horse to carry the normal gene, the ApoE2 gene, into the cells of the brain. The cells then make a buoy to embed the brain with the ApoE2 and hopefully convert the brain of an ApoE4 homozygote to that of an ApoE2 ApoE4 heterozygote.

Being Patient: Tell us how you engineer viruses to deliver genes for gene therapy. Viruses typically work through our body, and then they’re gone. How does that work?

Crystal: First, what we do is we engineer the virus, so it can’t cause harm. It’s important that we take out the parts of the virus that cause harm. The second thing is the way this virus works is it enters the cells. In this case, in the brain, it goes to the nucleus, that’s where the genes are, and it just sits there. It hijacks the nuclear machinery to make the new protein. In this case, a pointer to it just sits there, as long as the cell is acquiescent, and our cells in our brain are class, and they’re not turning over all the time. So, as long as the cells are not turning over, it just sits there and functions forever. At least in experimental animals, we know that we can genetically modify the brain for the life of the animal.

Being Patient: At what stage are we in determining whether or not gene therapy will really work for neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s?

Crystal: That’s going to take a long time. Studies have just started. We started this at Weill Cornell in our academic program, but we can’t do these big studies — we need a company for that. I was lucky enough to start a company called Lexeo Therapeutics, and they’re carrying out the studies now in multiple sites around the country. The important thing is, first, showing it’s safe. Secondly, to show that you can actually get ApoE2 into the brain and that it will persist. Then, the hard part is proving that it really works, which takes large numbers of patients, and that’ll take several years.

Being Patient: Is gene therapy for Alzheimer’s only for people with a genetic predisposition?

Crystal: There are really two groups of individuals related to ApoE4, those that inherited from both parents, that is what we call the ApoE4 homozygotes. There are about a million people in the United States that have ApoE4 homozygous, so they’re at the highest risk, but also a risk, or individuals that are what we call heterozygotes. They inherit one ApoE4 gene together with another chain, like ApoE2 or ApoE3, and we can help them as well. We’re starting with ApoE4 homozygotes, but if this works, then it could be expanded.

“We’re starting with ApoE4

homozygotes, but if this works,

then it could be expanded.”

Being Patient: How many people have ApoE2, and what do we know about the protective factor versus ApoE4?

Crystal: The population of ApoE2 is about 10 to 15 percent, ApoE4 is probably at five to 10 percent, something in that range, and the ApoE3 is the rest. I’ve sequenced all my genes and know I’m an ApoE3. So, as an example, I have an average risk. In terms of how ApoE2 functions, ApoE has many different functions in the brain. As you know, in Alzheimer’s, there is the amyloid accumulation and the phosphorylated tau tangles accumulation. This doesn’t pay attention to whether it’s amyloid or tau because it’s working at a more proximal level. So, it’s working at a level above that in terms of mechanisms of disease. So actually, ApoE has many different functions in the brain, all of which relate in terms of improving amyloid accumulation as well as tau and tau tangles and a whole bunch of other mechanisms as well.

Being Patient: It’s also been described to me as a cholesterol transport gene. What is the interaction between that gene and the formation of plaques and tangles that puts people at risk, especially if you have ApoE4?

Crystal: That’s a good and very complex question. So, ApoE is made in the brain in astrocytes and glial cells, and it forms the particles that carry cholesterol which is picked up by these neurons within the brain, which have the receptors for ApoE. A lot of it has to do with the binding of ApoE to what is called heparin proteoglycans, which are part of our extracellular matrix. We know that ApoE4 binds very tightly and forms initius for the development of amyloid and tau, whereas ApoE2 binds very little. So, that’s part of the mechanism, but there are several other mechanisms as well, and that’s still being investigated. There are papers coming out all the time in terms of why ApoE2 is better than ApoE4.

Being Patient: Let’s talk about the work Lexeo Therapeutics is doing. What’s the process for gene therapy in these trials?

Crystal: For any new drug, and this is a new drug, the most important thing is safety. So, those initial studies are really safety studies but also use biochemical markers to determine whether it works. We sample the cerebral spinal fluid, the fluid bathing the brain, and we sample that before. After that, we can measure ApoE4, and ApoE2 levels, what the ratio is, as well as some other markers as well. So that tells us, in fact, are we making the drug? And does it persist? And are we making enough?

Being Patient: Is gene therapy being used successfully in diseases other than Alzheimer’s? Is there something to compare this technique for Alzheimer’s with another disease state?

Crystal: Gene therapy started back in the late 1980s or so, when we and many others started the field. There are now some approvals for gene therapies, for example, spinal muscular atrophy, the SMA children, the floppy babies, who now can sit up, and that’s an approved therapy. For example, there is an eye disease that has been cured by Gene therapy, a hereditary eye disease. I think you’re going to see, over this year and over the next several years, several approvals of other gene therapies for other forms of the disease. We know that the technology works, the question is getting it right for a problem like Alzheimer’s.

Being Patient: How far away are we from learning whether or not gene therapy will work for Alzheimer’s disease? And is it going to be a one-time treatment, like an injection?

Crystal: These trials, the large phase three trials, take several years, so it’s probably five, six years before we know.

“We know that the technology

works. The question is getting it

right for a problem like Alzheimer’s.”

It’s a very simple procedure. It’s done on your imaging. So, with the needle, it goes to the right place, local anesthesia to the back of the neck. It’s just a small needle that goes directly into the cerebral spinal fluid in the back of the neck. So, it’s an outpatient procedure that doesn’t hurt. That takes about an hour, the whole procedure.

Being Patient: What is the risk to this exploratory work with genetics to the patient population?

Crystal: We carry out a significant amount of safety studies and experimental animals before we go to humans. The regulatory bodies, the FDA, of course, require that appropriately. But we still have to know in humans whether it’s safe or not. The viruses that we use, or we know, are safe and experimental animals, but on the other hand, the immune system might be able to see the virus and create a defense against it. So, there’s a whole variety of possibilities in terms of safety. So far, everything looks safe, but you have to do the studies to prove that.

Being Patient: Are there other methods of gene therapy out there that you’re aware of for preventing Alzheimer’s?

Crystal: Well, there are certainly strategies. Another strategy, for example, was to try to reduce the ApoE4 in the brain. Then there are strategies many pharmaceutical companies are working on in terms of monoclonal antibodies directed against amyloid, against tau. These also could be delivered by Gene therapy. There’s work going on to see whether or not, instead of direct administration to the cerebral spinal fluid, you can give it intravenously and will go into the brain?

So, there’s a lot of work that’s going on throughout the world, in terms of this, with a lot of attention to gene therapy. As I mentioned, gene therapy is essentially a drug delivery system. What we’re delivering is a gene. The technology has been developed over the last 30 years and is now coming to fruition, which really is beginning to work in many diseases.

Being Patient: Thank you for your research. We look forward to understanding more about gene therapy, and it also really highlights how people who hold the Alzheimer’s gene really do have a big role to play in determining how much more we understand Alzheimer’s disease.

Crystal: It’s the individuals who participate in the trials who are the real heroes because, without them, we could not move along and develop drugs like this. So, I would encourage people to think about participating in trials. These go on all over the country, and it’s really the participation of people with Alzheimer’s that make this possible to be able to develop a cure.

Katy Koop is a writer and theater artist in Raleigh, NC.

How does a person get their genes e4 tested to see if they have e-4 from both parents?

You can do it with consumer tests like 23andme or a blood test at your doctor’s office. Please note that these tests aren’t covered by insurance but are readily available. The cost for a home test is around $200. Experts recommend consulting with your doctor first because you he or she may want you to see a genetic counselor before administering a test.