Rare Alzheimer’s variants strike younger and act faster. Unusual symptoms mean they’re often missed by doctors.

Most people with Alzheimer’s disease begin to experience its best-known symptoms, like memory loss, in their late 60s. But about three percent of Americans with Alzheimer’s develop symptoms years or even a decade or more earlier, and research shows that when Alzheimer’s strikes early, it’s more likely to present in unusual ways — affecting functions like vision or speech first.

These rare forms of Alzheimer’s have long been overlooked and hard to diagnose — but that’s starting to change, thanks to better diagnostic tools and growing awareness.

Atypical types of Alzheimer’s don’t start in the brain’s memory center

Alzheimer’s symptoms are the result of neurons dying off in the brain. The disease’s earliest symptoms can vary, depending on where in the brain these neurons die first. At a molecular level, all Alzheimer’s cases involve the build-up of two abnormal proteins: beta-amyloid plaques and tau tangles. “The amount of amyloid is — throughout the brain — about the same between these different variants” of Alzheimer’s disease, Indiana University neurologist Liana Apostolova told Being Patient. But tau has a more specific relationship to these dying neurons, she explained: “It’s the tau protein that localizes to various different areas of the brain.”

In typical cases of Alzheimer’s, tau tangles first spread through the brain’s medial temporal lobe, a relatively isolated region that includes the hippocampus, the brain’s memory hub and navigation system.

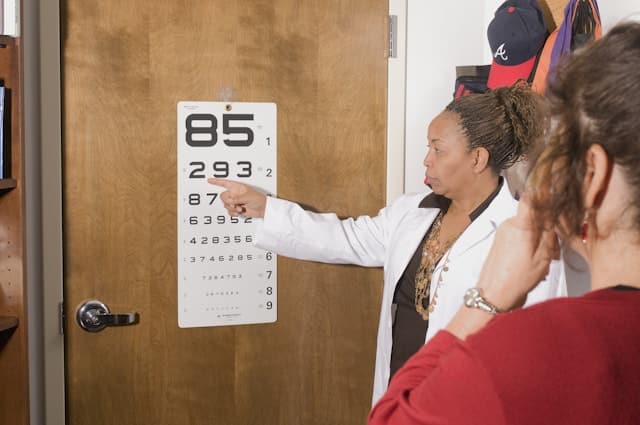

But when tau tangles first attack the posterior — or back — of the brain, they cause posterior cortical atrophy. In these cases, neurodegeneration begins in the occipital lobe, the brain’s visual processing center, so people don’t experience hallmark memory loss and difficulty completing tasks as the first indicators that something is wrong. Instead, their early symptoms will be blurred vision and difficulty reading.

In another rarer variant of Alzheimer’s, tau tangles accumulate in the left temporal lobe of the brain, where most people form and make sense of language. And that means difficulties with communication are the first symptoms. These cases result in logopenic variant primary progressive aphasia. People with this type of aphasia will struggle to recall specific words, forcing them to explain the word they are looking for. “For instance, if they want to say suitcase and they cannot come up with the word suitcase, they might say ‘the thing you carry your clothes in when you travel,’” Apostolova said.

When tau builds up in the brain’s frontal lobes, where decision-making and planning occur, this can cause a behavioral variant of Alzheimer’s disease, where changes in a person’s personality appear first. This form of Alzheimer’s could cause a person to lose interest in the things they enjoy, develop new repetitive behaviors, and begin to act inappropriately in social situations.

It is not yet clear why tau tangles start in different places in different people’s brains — scientists simply haven’t collected enough long-term data about people with these rarer Alzheimer’s variants. To address the dearth of knowledge, Apostolova launched the Longitudinal Early-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease Study (LEADS) in 2021. Her team continues to enroll new participants in their study, and they hope to generate enough data to answer these types of questions in the future. At the moment, she speculates that both genetics and environmental factors may play a role in determining an individual’s unique tau pathology.

Atypical variants, faster disease progression

According to Colin Groot-Remmers, a neurologist at VU University Medical Center Amsterdam, people with atypical variants of Alzheimer’s often go through longer diagnostic journeys than those with more typical symptoms.

For instance, a primary care provider may refer a patient complaining about worsening eyesight to an ophthalmologist as a first step, rather than sending them to a neurologist. “If those problems don’t go away and get worse and worse, you get referred to a center like ours,” Groot-Remmers told Being Patient.

Even then, it can be a challenge for a trained neurologist to distinguish between these subtly different neurodegenerative disorders. For example, the behavioral variants of Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia have overlapping symptoms that can make them hard to tell apart.

New developments in more advanced, more accessible diagnostic tools may help close these gaps. For example, the growing availability of blood-based biomarker tests and a growing emphasis on establishing diagnostic criteria for these atypical variants is helping more healthcare providers figure out what’s going on earlier in the course of the disease, when initiating treatment could still be possible.

To help neurologists make more informed recommendations about how aggressively their patients should pursue treatment, Groot-Remmers and his colleagues decided to compare survival differences among people diagnosed with Alzheimer’s.

In a recent Neurology study, they showed that people with atypical variants succumbed to the disease almost a year earlier than those with typical symptoms.

The researchers identified 2,081 patients who were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in the Alzheimer Center Amsterdam. In addition to clinical symptoms, each patient had tested positive for beta-amyloid abnormalities via a PET scan or lumbar puncture. The researchers also reviewed the patients’ medical files and determined that 280 of them had an atypical variant.

In July 2024, they analyzed public records for any death certificates belonging to the patients in their sample and found that the median survival time for people with atypical variants was 6.3 years, compared to 7.2 years for people with typical Alzheimer’s. Further, a diagnosis of an atypical Alzheimer’s variant was associated with 31-percent higher risk of mortality.

The study had its limitations: Because Groot-Remmers’ team focused on the patients’ first visit to the Alzheimer Center Amsterdam, Groot-Remmers said that they could not be certain if all the patients started at the same stage of the disease. Their results could reflect diagnostic delays for people with atypical variants, or they could indicate that atypical variants progress more quickly.

So, why are these atypical variants more aggressive? Groot-Remmers theorized that they could be inherently faster-acting because they begin in portions of the brain that have more connections through which tau tangles can spread, leading to faster neurodegeneration. But he stressed that plenty of other factors could play a role in determining a person’s risk of mortality. For instance, in the case of PCA, visual impairment could increase the likelihood that someone gets into an accident.

Regardless, Groot-Remmers said that the results of his study should encourage doctors and patients to consider the available options as quickly as possible once they have confirmed a diagnosis of an atypical variant.

As diagnostic tools and standards continue to improve, Groot-Remmers thinks more and more of these discussions will take place when patients still have time to consider taking disease-slowing treatments. “We are moving in the right direction,” he said.

But to keep moving forward, researchers need to continue collecting data on atypical variants through long-term studies like LEADS, which is currently enrolling individuals with early-onset Alzheimer’s at research sites across the United States. “People should get enrolled,” Apostolova said. “Without science, we’re not making progress.”