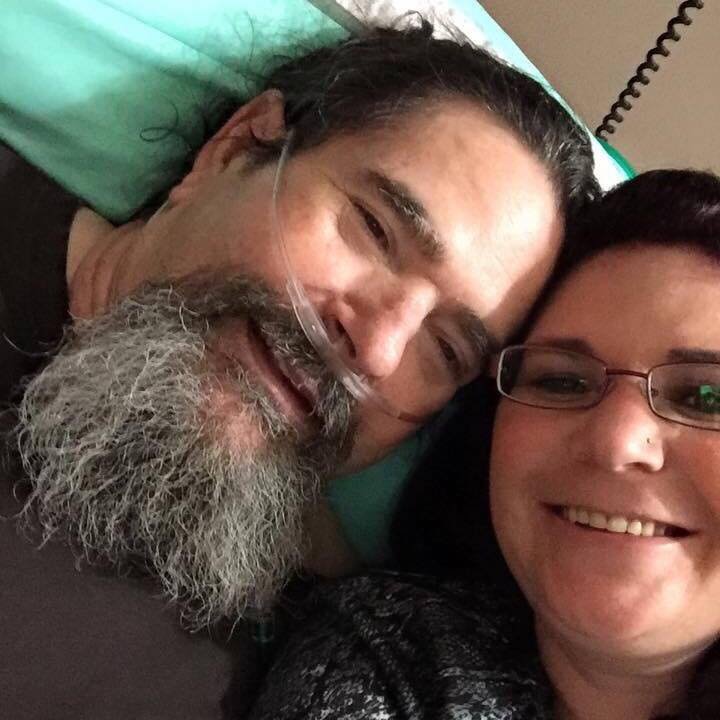

Jamie Scudder

I wish we would’ve gotten to take him out fishing or to do other fun activities before he left us, but I’m grateful that he was always surrounded by his family. Make the most out of your loved one’s life because there will come a time when they can’t leave the house or do anything, and then it’s too late.

July 20th, 2018

In a recent post, Connie Welshonse described how Lewy body dementia (LBD) is different from other forms of dementia, including her father’s acute awareness of his own memory loss. Connie’s sister, Jamie Scudder, offers strategies caregivers can use to help their loved one with dementia feel more comfortable, based on her experience as a nursing assistant working with dementia patients and watching her father’s decline.

There’s a marked difference between LBD, Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia. Doctors initially diagnosed my dad with Alzheimer’s, but my siblings and I started to question his diagnosis because the characteristics he displayed were not typical of an Alzheimer’s patient. I have been a certified nursing assistant (CNA) for over 24 years and work with dementia patients. Typically, when someone has Alzheimer’s, they don’t shift in and out of a dementia-like state. However, we noticed that sometimes, my dad was lucid and aware of the time, date and who we were, but other times, he was not. When he went into a dementia-like state, then came out of it, he knew that he had experienced something different and scary. LBD patients are aware that they’re losing their memory, which must be very traumatic. When I think of Robin Williams, whose autopsy showed LBD qualities, I’m reminded of how frightening it can feel to not be in control of your mental state. If your loved one has LBD, it’s important to be honest with them about their condition and to reassure your loved one that they’re not alone and that you understand that what they’re going through is scary.

My dad took great comfort in personal touch. We often held his hands and tried to talk him through what he was experiencing. We’d say, “OK, this is a really scary place you’re in, but you’re better now.” We couldn’t fully take his pain away, but we wanted him to know we were there, since he never wanted to be alone. We’re not sure how LBD affected my dad’s eyesight, but his eyes were often open while my mom was sitting right next to him and he’d ask where she was. We’d get him to look directly at her, then he’d say, “There you are.” In the final stages of the disease, Dad could only see memories from his past. We’d wave our hands right in front of his eyes, but it was like he couldn’t see. Even so, we sat with him so that he knew he always had family members nearby.

My dad had an underlying diagnosis as well that really affected him: multiple system atrophy (MSA). The MSA exacerbated his LBD symptoms; with LBD, you already forget how to eat and function, and my dad also developed balance problems. As his body parts started to shut down, we didn’t know if he was passing out or simply losing his balance. All of a sudden, he’d just fall over. As a CNA, I often use dancing and singing to help my residents, which also worked for my dad. We tried to distract him so that he wasn’t overly focused on what we were asking him to do. For example, he’d sometimes try to lift up his foot, but he’d get stuck and his foot would start shaking. When we wanted to help him walk, we’d say, “OK, let’s march—left, left, left, right, left,” and then he knew we were moving forward. If we wanted to help him line up his chair, we’d make a dance out of it and say, “to the side, reverse, back it up, back it up.” My dad had a huge sense of humor and a lot of dignity, so we tried to make a scary experience fun for him. Often, he knew his words were jumbled or he forgot certain words. As my sister wrote, we tried to help him figure them out with games like Charades without making him feel as if he was losing his mind.

As a CNA, I also learned a lot about what to watch out for. I was aware that with LBD, my dad may get aphasia, a condition that results in trouble finding words. I knew that when my dad was swallowing, I had to check his mouth for food to ensure he was actually swallowing and that he wasn’t aspirating—breathing the food into his airway, which is a common cause of lung infection in dementia patients. Education is so important. I hear a lot of people say, “Dementia is dementia,” which irks me because that’s not true. Dementia that you develop from a traumatic brain injury may be different from Alzheimer’s or LBD, which both affect different parts of the brain, resulting in different symptoms. We had to do all of the research on our own because the doctors often told us that they weren’t sure why my dad was experiencing certain symptoms.

If your loved one is suffering from LBD or another form of dementia, you should make the most out of their experience by letting them do what they want to do. My dad wanted to go fishing a lot, but we were so busy with doctor’s appointments and day-to-day life. I wish we would’ve gotten to take him out fishing or to do other fun activities before he left us, but I’m grateful that he was always surrounded by his family. Make the most out of your loved one’s life because there will come a time when they can’t leave the house or do anything, and then it’s too late.

Jamie Scudder has been a CNA for nearly 25 years and was a caregiver for her father, who had Lewy body dementia (LBD). She runs the Facebook support group Lewy Body Dementia Group In Memory Of Rickey Simas.