A key protein might stall like an engine in a broken car. Neuroscientist Michael Wolfe is working on a fix — but a federal funding slowdown could stall him, too.

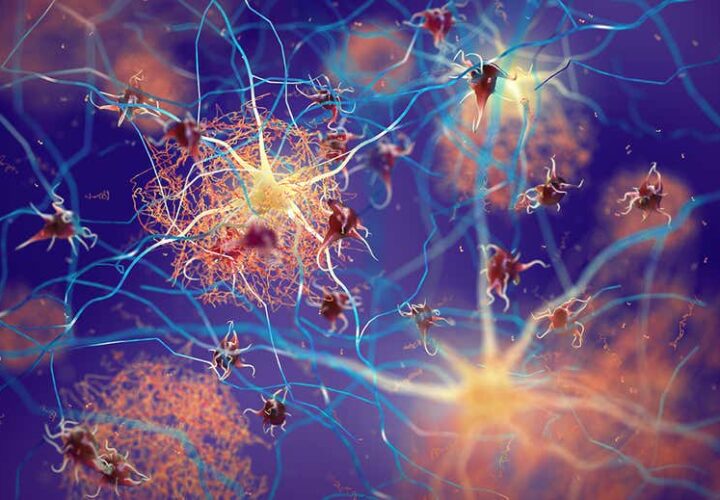

At first, scientists had no idea what might cause Alzheimer’s disease and had no underlying protein or pathway to target with treatments. Then came the genetic studies: By looking at families with an inherited form of Alzheimer’s disease, scientists gleaned clues. This form of Alzheimer’s had a clearer cause: Genetic mutations that increased the levels of beta-amyloid leading to downstream damage, cognitive decline, and neurodegeneration.

To stop the damage, researchers in the 2010s bet big on a class of proteins called secretases, which are involved in making beta-amyloid proteins. Drugs that prevented secretases from working were developed and tested. Paradoxically, they worsened cognitive decline even though they lowered the levels of beta-amyloid. These drugs were largely abandoned by pharmaceutical companies in favor of other approaches like anti-amyloid therapies.

But what if scientists had the right target — just the wrong strategy?

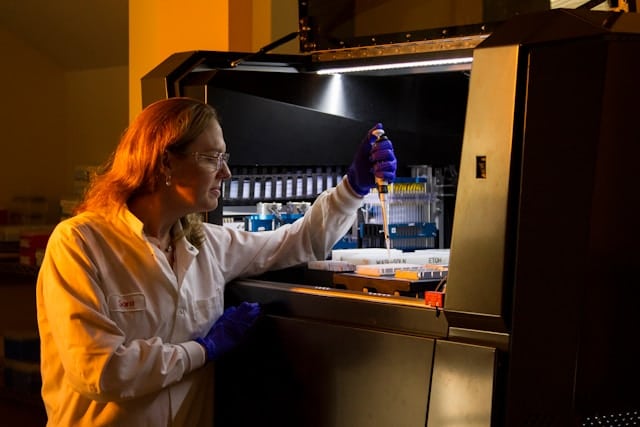

Gamma secretase, one of these proteins, might still be key to understanding Alzheimer’s. Instead of overproducing toxic fragments, it may be sputtering and stalling like a faulty engine. Michael Wolfe, a professor at the University of Kansas, is working on a fix.

“We have come up with an alternative to the amyloid hypothesis,” he told Being Patient. “We find that it’s the stalled process, not the [amyloid] products, that’s triggering neurodegeneration.”

For 17 years, Wolfe has received NIH funding to study gamma secretase and its role in Alzheimer’s. Now, just as his lab is preparing to test potential drug treatments, his research is at risk of running out of gas.

Is your gamma-secretase a lemon?

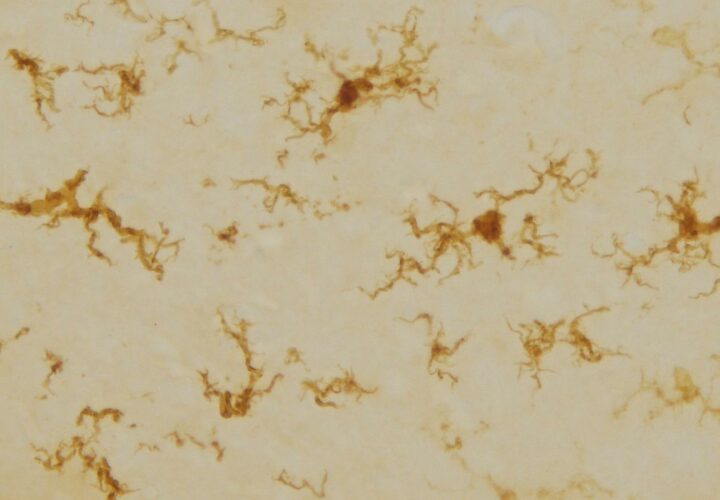

Mutations in the presenilin gene (PSEN1 and PSEN2) are known to cause familial Alzheimer’s. Normally, gamma secretase latches onto amyloid precursor protein (APP), slices it, and releases beta-amyloid. But in people with PSEN mutations, Wolfe’s research suggests gamma secretase misfires.Instead of efficiently cutting APP, the complex stalls, with the precursor protein stuck inside. Wolfe calls this a “stalled complex” — a molecular traffic jam that may trigger toxic cascades in brain cells.

This begins “triggering a toxic response,” he said, which may lead to cognitive decline and neurodegeneration.

To test this theory, his laboratory is using computational models, cells grown in a dish, and animal models to understand why. His lab’s choice of animal model: small nematode worms called Caenorhabditis elegans. C. elegans is widely used as a model organism by neuroscientists because it is small and transparent, and scientists have mapped out every single one of its brain cells.

His experiments confirmed that getting rid of gamma secretase function altogether doesn’t destroy these connections, but in line with his hypothesis, when gamma secretase stalls the connections in the worm’s brain cells, they deteriorate.

“What we’re trying to do is target validation,” said Wolfe. “It’s a very early stage of drug discovery where you try to understand the molecular basis of the disease and identify where you can intervene with a drug.”

The next step is testing drug compounds to see if they can stop gamma secretase from stalling. There are well-defined libraries of compounds and approved drugs that are available for researchers to screen en masse. If any succeed, Wolfe says, they could be fast-tracked for clinical trials.

But time — and funding — are running out.

One of Wolfe’s grants is up for renewal on June 10th. The grant provided funding for three years of research and will fund two additional years if a review committee of independent experts determines the project has made enough progress.

Funding at the NIH and reviews of new grants have slowed to a halt since the Trump Administration took over. In late January, meetings for grants reviews were canceled, while most external communications, travel, and spending were frozen. As of March 5, a small handful of meetings have been reinstated.

Wolfe was supposed to serve on one such panel — it was cancelled at the last minute and pushed to, finally, the middle of last month. “I’ve heard this from some other colleagues that these grant reviewing panels are not meeting and that no new funding is being approved,” he said. As reported by The Transmitter, funding of neuroscience grants this year lags 77 percent behind a nine-year average of previous years.

The process has restarted now after months of delays, Wolfe says, but the future of his research is still uncertain — a condition scientists across the U.S., and across scientific fields, are distracted by right now, with everything lurching forward on “what if”s. “I don’t know if there’s going to be sufficient personnel to review these grants,” said Wolfe. “If that grant doesn’t get renewed, my lab will shut down.”

My partner was diagnosed with Parkinson’s almost 5 years ago. His disease has progressed significantly in the past year, and he begun to have delusions. He also had side effects from carbidopa/levodopa, which we decided to stop, and our primary physician decided he should start on PD-5 formula 4 months ago from UINE HEALTH CENTER. He now sleeps soundly, works out frequently, and is now very active since we started him on the PD-5 formula. It doesn’t make the Parkinson’s disease go away, but it did give him a better quality of life. We got the treatment from www. uine heathcentre. c om