A new approach to genome sequencing newly identifies 13 rare gene variants potentially associated with Alzheimer’s.

Dr. Rudy Tanzi, vice chair of neurology and director of Massachusetts General Hospital’s genetics and aging research unit, is a household name in the world of Alzheimer’s research for co-discovering a number of gene variants linked to early-onset Alzheimer’s and familial Alzheimer’s, including APP (the amyloid protein precursor gene) and presenilin genes PSEN1 and PSEN2.

Now, Tanzi and colleagues at Mass General have leveraged a new approach to genome studies — whole-genome sequencing — and with this tool, discovered 13 more gene variants that appear to be linked to Alzheimer’s. On an individual level, knowledge of genetic variants can bring awareness and possibility for prevention. On a population level, it may mean potential new drug targets — and hope for new therapies.

A new study, published this month in Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association details how Tanzi’s team sought out families in which multiple family members had Alzheimer’s. From 605 families with a history of the neurodegenerative disease, they recruited 2,247 participants and sequenced their whole genomes, searching for commonalities in unfamiliar gene variants. They also incorporated genomic data from an additional 1,669 people.

Among the results, 13 previously unknown, rare variants emerged.

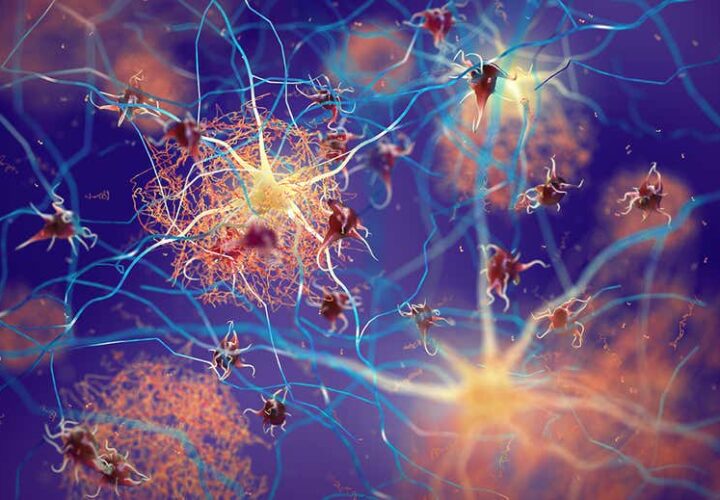

According to Tanzi, these newly discovered variants could offer some of the first genetic links between Alzheimer’s and neural development, the function of synapses (connections between brain cells that transmit chemical and electrical communication signals), and neuroplasticity (the ability of neurons to reorganize the brain’s neural network).

“Rare gene variants are the dark matter of the human genome,” Tanzi said in a statement. “With this study, we believe we have created a new template for going beyond standard [genome-wide association studies] and association of disease with common genome variants, in which you miss much of the genetic landscape of the disease.”

A New Approach to Genome Sequencing

According to Mass General, the existing standard approach to genome-wide association studies isn’t precise enough to catch all the genetic clues researchers need to solve the Alzheimer’s mystery. Current GWAS methods miss the rarest gene variants — those occurring in less than 1 percent of the population. But in Tanzi and colleagues’ whole-genome sequencing, which scans every bit of DNA in a genome, they can catch those rare muations.

The Secrets in Our Synapses

In addition to APP and the PSEN genes, Tanzi and colleagues also previously identified 30 genetic variants related to chronic inflammation in the brain, which is linked to the development of dementia, as Tanzi explained in a Being Patient Livetalk. “We found the first Alzheimer’s gene that causes neuroinflammation — CD33 — and another, TREM2. Those genes control the neuroinflammation in the plaques and tangles,” he said.

However, according to Tanzi, even more than neuroinflammation, the loss of synapses is the neurological change most closely correlated with the severity of dementia — one of the defining symptoms of Alzheimer’s. These signals are a vital part to forming memories and maintaining brain health, and to date, no clear genetic link between Alzheimer’s and synapse damage or loss has been discovered.

“It was always kind of surprising that whole-genome screens had not identified Alzheimer’s genes that are directly involved with synapses and neuroplasticity,” Tanzi said of the new study.

There have been other indications that synapse decline in Alzheimer’s has a genetic link: One study published by researchers at the University of Edinburgh in 2019 found that in people with Alzheimer’s, brain synapses contained clumps of protein thought to be associated to Alzheimer’s symptoms called clusterin, and that people with the ApoE4 gene, one of the best-known Alzheimer’s genetic variants, had more clusterin and beta-amyloid in their synapses than Alzheimer’s patients who did not carry ApoE4.

What’s Next for These Novel Gene Variants?

Tanzi and colleagues are now gearing up to use Alzheimer’s models to study the behavior of neurons affected by these genetic variants — and with these recent advances, they have a great advantage.

“This paper brings us to the next stage of disease-gene discovery,” lead author Dmitry Prokopenko of Massachusetts General Hospital’s McCance Center for Brain Health said in a statement, “allowing us to look at the entire sequence of the human genome and assess the rare genomic variants, which we couldn’t do before.”