Should “AD” stand for Alzheimer’s disease, or for Auguste Deter, the patient whose case was first described? Neurologist Donald Weaver explores the history.

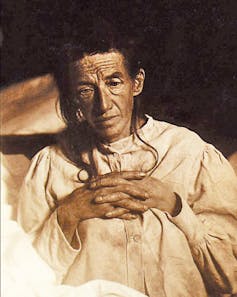

Auguste Deter was born 175 years ago on May 16, 1850. Though the story of her life is not widely known, it should be. Through her suffering and dignity, Deter puts a much-needed human face on the tragedy of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), one of the most important medical problems currently confronting humankind. Auguste Deter reminds us that AD is a disease of people, not proteins.

Often, scientists reduce AD to a disorder of shrunken brain cells or misfolded proteins. However, AD is so much more.

It is a disease that impairs thought processes and personal memories — the very essence of what makes each one of us an individual capable of hopes, dreams, love and being loved. AD is a very human disease and a very human struggle for individuals, their families and society as a whole. Deter is a crucial reminder of the human aspects of this devastating disease.

‘I have lost myself’

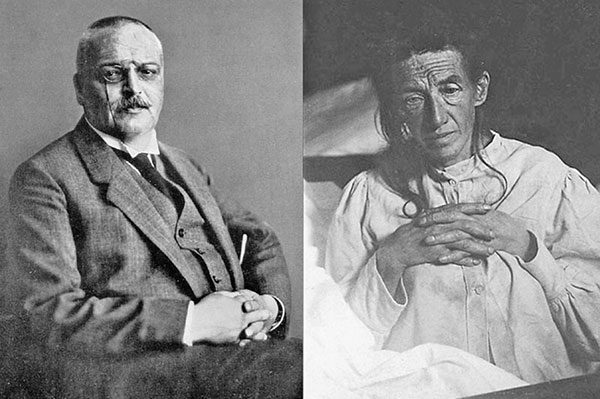

Although dementia had been recognized for centuries, Deter was the first person officially diagnosed with the type of dementia now recognized as Alzheimer’s disease.

Born Auguste Hochmann into a working-class family, the financial hardships imposed by her father’s early death forced Deter into full-time employment as a seamstress at age 14. She continued this work until marrying Karl Deter, a railway clerk. The couple moved to Frankfurt, Germany where they lived as a happy and harmonious family with their daughter, Thekla.

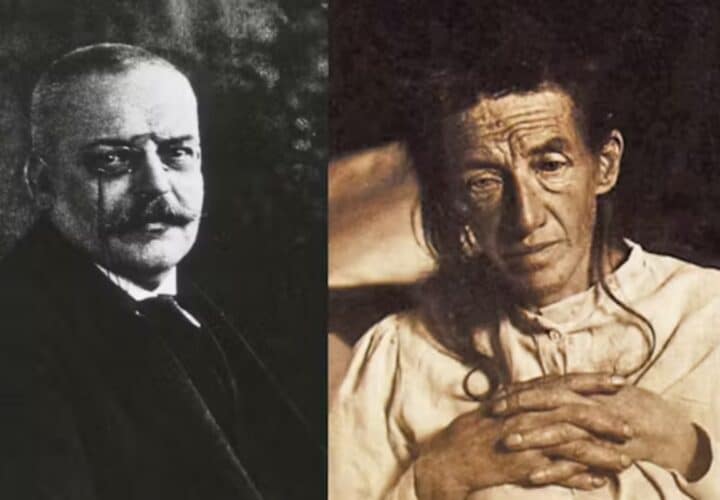

Tragically in the spring of 1901, this loving and caring 51-year-old woman began to be incapable of routine household activities. Soon, due to her progressive memory loss and intellectual impairment, she was no longer able to function on her own. She was admitted to the Frankfurt Psychiatric Hospital under the care of Dr. Alois Alzheimer.

Alzheimer asked her many questions to which she would sometimes quietly reply “Ich habe mich verloren.” (“I have lost myself.”) Sadly, her relentless cognitive decline continued. On July 12, 1905, Alzheimer recorded that Deter’s deterioration had progressed such that she was lying on her side in a pool of urine, knees drawn up, unable to communicate. She died on April 8, 1906 from pneumonia and infected bed sores.

Definitive features

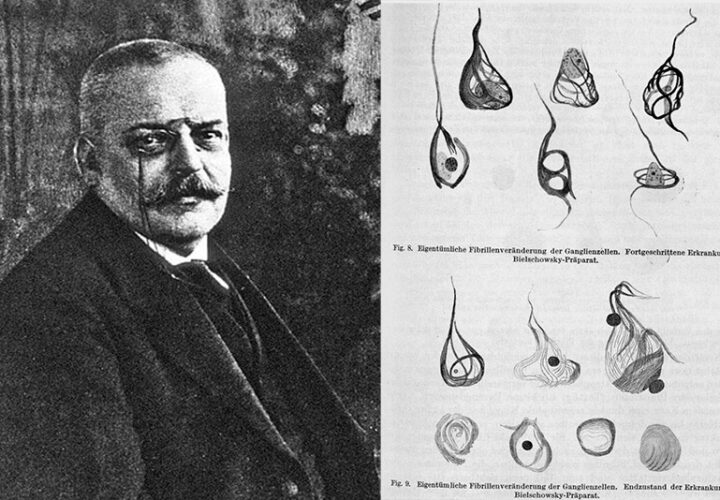

During the subsequent autopsy, Alzheimer identified not only Deter’s marked brain shrinkage but also localized clumps (“plaques”) of an unknown deposited substance as well as dense bundles of tangled fibres in what were once healthy brain cells.

These latter two observations — now recognized as amyloid plaques and tau tangles — have become the diagnostic features that define the pathology of AD. In 1907, Alzheimer published a scientific paper in which he described Deter’s brain and her “new” type of dementia.

Unfortunately, Alzheimer was unable to dedicate a long career to a more comprehensive understanding of this disease. He contracted rheumatic fever in 1912, dying of its complications three years later at age 51. Nonetheless, the Deter case report was sufficient to establish his legacy as the discoverer of Alzheimer’s disease.

As an inquisitive psychiatrist and pathologist, Alzheimer had been interested in medicine and science, not fame. He was not seeking to name a disease after himself. In 1910, Alzheimer’s boss, the renowned German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin, wrote the influential Handbook of Psychiatry – a textbook in which he named this newly identified type of dementia “Alzheimer’s Disease.” In doing so, Kraepelin’s textbook ultimately transformed Alzheimer’s name into a household word.

Meanwhile, in Prague

But does Alzheimer’s disease truly deserve to be called Alzheimer’s disease? There are other people who can claim contributions to the discovery of Alzheimer’s disease.

In 1907, the same year that Alzheimer published his single case description of Deter, a Czech psychiatrist named Oskar Fischer independently published a thorough structural analysis of plaques in the brains of 12 people with dementia. Between 1910-1912, he went on to analyze plaques and pathological brain changes in another 58 cases of dementia.

Arguably, Fischer made more important contributions than Alzheimer to the comprehensive description of the disease. Yet it is called Alzheimer’s disease, not Fischer’s disease.

There are many reasons for this. Fischer was Jewish and subject to antisemitism. He was not at a prominent German university and did not have a powerful ally like Emil Kraepelin promoting his career. And science is, after all, a very human activity.

Unfortunately, Fischer later became trapped in occupied Prague under the oppression of authoritarian Nazi rule. Fischer was arrested in 1941 and died in the Gestapo’s notorious Small Fortress prison on Feb. 28, 1942.

It seemed likely that Fischer’s seminal contributions to our understanding of dementia would be lost. Thankfully in 2008, Michel Goedert of Cambridge University rediscovered Fischer’s significant contributions stored in the archives of Charles University in Prague. This has restored Fischer to his rightful position as one of the discoverers of AD and retrospectively raises questions about the correct naming attribution of AD.

However, when considering the naming of AD, we must not forget Patient No. 1: Auguste Deter. Interestingly and fortuitously, her initials are AD. So, should AD signify Auguste Deter disease rather than Alzheimer’s disease? Should the Alzheimer-Fischer controversy be resolved by simply reassigning the AD abbreviation to Auguste Deter? Should the disease be named after its “first patient,” rather than the physician(s) who discovered it?

Medicine has a penchant for naming signs, symptoms and diseases after the physicians who first described them. We typically tend not to name them after the afflicted person. Perhaps this is done to preserve patient confidentiality; perhaps not.

But AD is a disease like no other. It’s very personal. It affects the memories, thoughts and emotions that define us as human beings. We must never forget that AD is a disease of people and families, not just proteins and fibrils. Deter tragically yet courageously embodies the human heartbreak of this dreadful disease.

Deter’s contribution to the 1907 single case report study by Alzheimer was immense: Deter’s life, illness and death are the story of AD. Deter should be remembered. It was and is her disease.![]()

As a 70 year old Canadian female, I recently was told that I have Alzheimer’s. I found the articles here to be very interesting. Thank you for these articles.

Hi Bonnie, thank you for being a part of our community. You might find this interactive guide on the 7 stages of Alzheimer’s helpful as you navigate your recent diagnosis: https://www.beingpatient.com/guide-seven-stages-of-alzheimers/?utm_source=organic&utm_medium=social – take care.